The air had barely a hint of chill to it, and the sun, just now rising above the horizon, would quickly get rid of that. Only a couple of passing rain showers each day cooled things off—one had just come through at dawn and another would likely arrive, if the last several days were any indication, precisely at three p.m.—but those only lasted a few minutes at most, just long enough to give everything a fresh bath.

We'd parked at a trailhead in the dark and walked a few hundred yards through moist forest to Trunk Bay Beach. Not a soul in sight. That's what stunned us most about St. John, the unspoiled crown jewel of the U.S. Virgin Islands: this tropical playground wasn't exactly off the beaten path, but there was never anyone in your way.

Running all over the island for the last several days in a Suzuki jeep with our gear in back, we'd found an amazing variety of beaches, easily accessible and with easy access to miles of coral reef. The drive from Cruz Bay up along the lush north shore of the island, over its mountainous interior and down to the arid east coast, was itself filled with sights a person will remember for a lifetime, but that was but a passing glance at all the adventures St. John held in store.

On the north coast, we'd hiked under forest canopies 75 feet in the air, beneath trees with exotic names such as bay rum, sandbox, kapok and hogplum, the undergrowth dense with vines like wild coffee, sweet lime and guavaberry. On the east side, we'd wandered through dry forests of turpentine trees, black mampoo and white cedar through low scrublands to a rocky shore pocketed with white sand beaches. Each hike, well marked by the park service, led us to the water, to another empty beach, to another unspoiled view.

Betsy hadn't done much snorkeling before this, but by now she was a pro. She slipped on her fins, walked backwards into the water, turned and waited for me to join her. We whispered our plan to stay close to each other and to shore, heading parallel to the coast along the inner edge of the reef. Masks down, thumbs up, we submerged, blew our snorkels clear and began to swim slowly across the surface.

I felt Betsy against me, weightless and fluid. She slipped her hand into mine and we floated together above a reef so vibrant in color and teeming with aquatic life it seemed almost to tremble.

I reached out my hand to brush gently at a school of blue tang, squeezing Betsy's hand lightly to signal my discovery. She squeezed back, hard, jerking with more urgency than usual. I looked up to see a huge sea turtle gliding a few feet ahead of us, going our way in no particular hurry. We followed along, side by side, communicating our utter amazement and joy without saying a word.

*

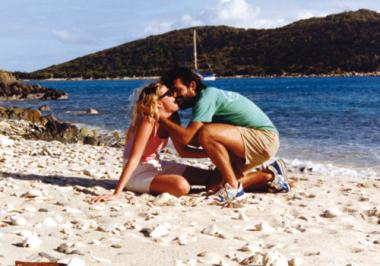

When Betsy and I were married in August of 1990, we had definite plans: no big wedding, no honeymoon.

We'd only known each other for about eight weeks, and while we thought ourselves too old to need anyone's approval, we knew that not all of our friends and family shared our confidence that our marriage wouldn't quickly implode. We didn't have any money: I worked as a freelance journalist, while Betsy was just finishing up her bachelor's degree after returning to college after a two-year hiatus spent working. But even if we'd had a few bucks, we wanted a completely private wedding—just us and a justice of the peace at the edge of Walden Pond in Concord, at the site of Thoreau's famously modest one-room house—and were initially loath to spend even a dime on something as expected as a honeymoon. We were cut of different cloth.

A year later, however, our perspective was quite a bit different than it had been on our wedding day. We had no regrets about our wedding, which had been capped off, to be perfectly honest, with a mini-honeymoon courtesy of one of my buddies, who put us up at an inn in Concord after our Walden Pond ceremony, and my mom, who sprang for a night at a swank hotel in Newport. But after a year of actually being married, after going through growing pains and sorting out the accommodations necessary to keep two very stubborn people from killing each other, we felt the need to do something big—something symbolic of our true readiness to take on life's many adventures together, hand in hand.

It was Betsy's idea that we should go someplace warm and beautiful and exciting, but we quickly agreed that it was time to have ourselves a real honeymoon.

The planning part was a mix of fun and frustration. We borrowed piles of travel magazines from the library—these were the days before one simply hit travelocity.com to plan a trip—and spent many hours comparing one exotic locale to another. We soon locked down on St. John, the most undeveloped of the U.S. Virgin Islands, with about eighty percent of the island held as a national park. Finding a way to pay for it was not so easy.

Eventually, I had to borrow money from one friend and lean on another, a guy who'd grown a small discount travel business out of the basement of Filene's department store into a successful national brand, to get me a deal. With $2,000 on loan and a little help from my travel agent friend booking a couple of discount airline tickets, a small villa in Cruz Bay and a jeep, we were ready to embark on a ten-day honeymoon to the Caribbean.

Today, nearly twenty years later, I still wince at the thought of how long it took me to pay my friend back. All along, my friend kept telling me she wouldn't have lent me the money if she'd needed it back in a hurry, but it bothered me nonetheless.

That one fleeting memory of being sick over borrowed money pales in comparison to the memories I have of Betsy and me, young and in love, playing together in paradise. All these years later, after all the major events like buying a home and building a career and having a child, I can still remember my honeymoon in vivid detail, as if it truly just happened.

Even now, when Betsy and I talk about the beginning of our love affair, we express no regret at having eloped, and while we have occasionally kidded about having a grand ceremony to renew our vows someday, we feel no real urgency for it. But our honeymoon—that's another story. We still find it hard to believe that it almost didn't happen. When we dare look farther up the road than our daughter's next soccer game or trip to the dentist, we plan a return trip to St. John for our second honeymoon.

*

Reading a piece in the New York Times travel section recently, I learned that St. John hasn't changed that much since we visited there in early 1991. There are more restaurants and clubs than there were then, some fancier hotels offering amenities that pamper affluent clientele as they expect to be pampered in 2009. But the National Park Service is a great neighbor to have if you live on an island that caters to tourists: developers can keep polishing up their little parcels, but they'll never (I hope) touch more than a small fraction of the island's twenty square miles.

That morning when we snorkeled off Trunk Bay Beach, we couldn't know, but might have guessed, that we were at one of the top ten beaches in the world, a designation bestowed some years later repeatedly by the vaunted publisher of Travel magazine, Conde Nast. Neither did we know that sewage pumped into the world's oceans, including the Caribbean, would decimate many thousands of square miles of ocean reef across the globe, or that the north shore of St. John would, until only recently, fare better than most other locales (scientific research reported last month revealed significant deterioration to the coastal reef due to a mysterious wasting disease that kills brain and star coral). We knew only that we were someplace very special at a very special time in our lives.

After we swam ashore, we stretched out in the sun to dry, still alone, still amazed by what we'd seen. After a while, hunger compelled us to wander back to the jeep, then over to the east side of the island, to a bohemian-inflected restaurant where we ate conch fritters and conch stew and fed tame sparrows oyster crackers from our hands.

That night, we would be back in this restaurant's bar, where we would hear news that the United States had launched its opening offensive in the first Gulf War, intent on driving Saddam Hussein's Republican Guard out of Kuwait and back over the Iraq border. The next day, we would read briefly about the war in the San Juan Star, sitting in this same conch joint, drinking coffee and feeding the birds.

In just five days, we'd be back in snowy Boston, but with nearly half our honeymoon left to go, we felt no anxiety, no pressure. The real world—the one with rent to pay and careers to build and wars to worry about—seemed far away. At that moment, we had plenty of time, but only for each other and the beauty all around us. Nothing else seemed to matter."