Even as Northampton community leaders craft plans to invigorate downtown without the fee-charging district a judge declared “null and void” in November, resentments simmer and questions swirl about what killed the 5-year-old Business Improvement District.

Amid the rancor, this much is clear: The BID’s demise had a lot to do with messy handwriting — and a sloppy approach to meeting legal requirements.

Before it was dissolved, the Northampton BID levied fees against downtown property owners and used the money to clear sidewalks, promote events and illuminate the streets with holiday lights and fireworks.

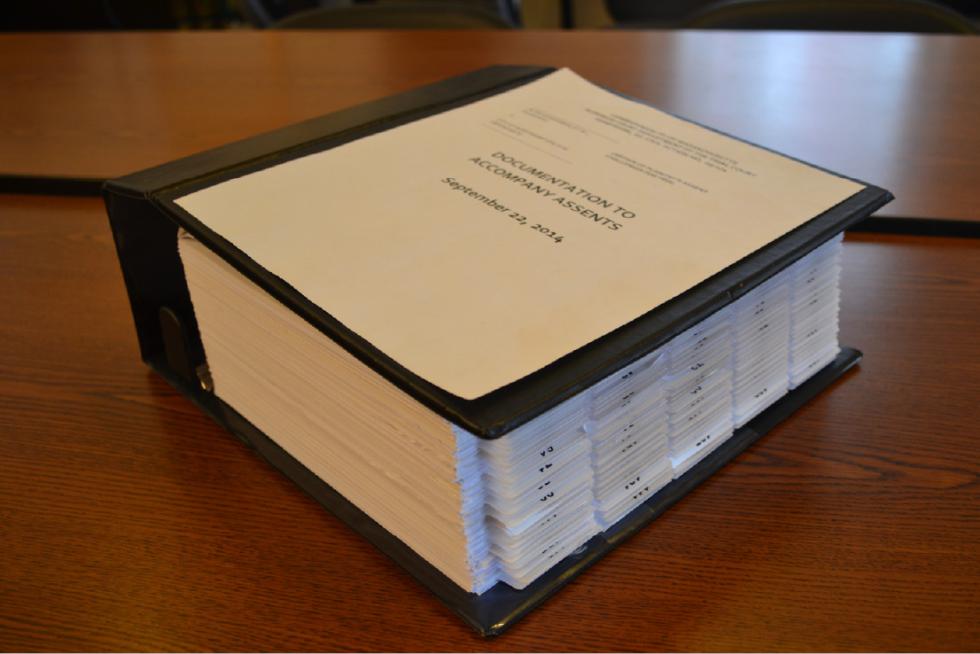

But in ruling that the BID had been illegally formed, Hampshire Superior Court Judge John A. Agostini pointed in part to 63 of the 305 signatures organizers presented to establish support from affected property owners — signatures that he said were illegible.

Example of a petition signature discarded due to illegibility

He wasn’t the only one who had trouble reading them, the judge noted. So did the city officials responsible for certifying their legitimacy under the requirements of Massachusetts law. But those officials did not take the time to establish the identity of signatories and confirm their connection to downtown properties, Agostini found. Therefore, he ruled, the BID “is and always has been null and void.”

So where did those 63 signatures come from? From the pens of legitimate property owners and duly authorized representatives? Or were they forged by some downtown boosters?

Valley Advocate reporters decided to find out. Combing through property records and corporate filings and then hitting the streets, telephones and email circuits, we reached out to the people who owned or represented these disputed 63 properties when the BID was formed.

In the end, we reached people associated with 60 percent of those parcels. (Others could not be found or did not respond to requests for comment.) And guess what they had to say?

To paraphrase: “Of course, we signed.” Did officials ask you to certify your signature before the BID was formed? “Nope.”

One of the messy John Hancocks belonged to Charles Bowles, who not only owns two Main Street properties, but also served as chairman of the BID board. During last fall’s trial over a lawsuit challenging the BID bought by prominent downtown property owners Alan Scheinman and Eric Suher, Bowles recalled the plaintiffs’ lawyers calling his signature unclear and unverified.

“They said it might as well be Mickey Mouse’s signature,” Bowles recalled. “Well, guess what? That would be me — Mickey Mouse.”

Other signatories were not as dismissive of the legal challenge, acknowledging that state law required Northampton to verify that 60 percent of affected property owners assented to the formation of the business improvement district before it was created in spring 2009.

“A BID is good for a city like this,” said Robert Steinberg, who was living in a condo downtown and confirmed that he had signed. “But it sounded to me like the judge felt he had no choice. The BID was founded improperly and someone had to say so.”

While some complain that the legal decision turned on a “technicality,” the judge noted that establishing the authenticity of a district with the power to levy fees was no small matter to the Legislature that had authorized them. “Because these powers are so expansive … BID petitions were to be scrutinized carefully and repeatedly to ensure compliance,” the judge wrote.

Once BID proponents had gathered up the signatures of affected property owners, they presented them in late 2008 to Northampton City Hall. There, City Assessor Joan Sarafin and City Clerk Wendy Mazza issued official certifications that legal requirements had been met. In March 2009, the City Council declared that the BID was good to go.

Problem is, none of those officials had verified the signatures.

“The failure by either Mazza or Sarafin to make a determination as required by (state law) that the criteria for establishing a BID had been met renders their certifications arbitrary and capricious,” the judge wrote. He then took aim at the City Council, which he said had “abdicated its responsibility” by failing to make “a meaningful or independent determination” that the BID was formed with the approval of property owners.

When the judge’s ruling came out before Thanksgiving, Sarafin and Mazza declined to answer most questions from reporters. But as the Advocate prepared this report, they agreed to speak.

And both said they felt like they had been unduly blamed.

“I feel like Joan and I were hung out to dry in this process,” said Mazza. “And there were other people involved in this that walked away unscathed. So, I’m really disappointed that we took the brunt of the heat for this. I have very broad shoulders; I can take the criticism. But some of that criticism needed to be spread around.”

While BID organizers say they have known all along that the signatures they gathered were valid, Scheinman said BID organizers and city officials were wrong to cut procedural corners and ask people to accept signatures on good faith.

“I knew what they had done, and the way they did it was wrong,” he said, “and, if they were allowed to do that, I’m vulnerable to anything.”

Questions from the start

The BID’s origins date to 2006, when some Northampton business leaders were seeking a better way to make downtown appealing to shoppers, dinner-goers and other potential customers. By pooling resources, they reasoned, they could do a better job organizing events, clearing sidewalks of snow and trash and beautifying the city with flowers, lights and fireworks.

The Legislature’s authorization of business improvement districts — which would collect fees, optional at first and mandatory later on — seemed to offer a promising path.

But state law imposed a key requirement: that BID organizers provide “assents” from 60 percent of the property owners within the proposed district. From 2007-2008 members of a BID steering committee sent out a series of mailings promoting the district, including one containing an assent form that owners were asked to sign and return.

“We agreed that the BID was a really good idea,” said Kate Collins. She and her husband Robert Carroll were living on South Street in April 2008, when she remembers a petitioner stopping by with an assent form. She added that strong local business and a vibrant commercial downtown were the main reason she had moved to Northampton from New York City the previous year. “It’s a little city, but it’s got a huge conscience. I love that about this place.”

But the effort also had its detractors, including Scheinman and the property ownership groups led by Suher. Even as the BID organizers were presenting their formal petition to City Hall, Scheinman was raising questions about the legitimacy of the signatures. On April 13, 2009 — one month after the City Council had approved the BID — the dissident property owners sued. It was that lawsuit that eventually led to Agostini’s ruling.

BID organizers needed the signatures of 297 property owners (or authorized representatives) to meet the 60 percent threshold. Thus, a failure to verify more than a handful of the 305 they presented would have killed the BID before it ever began.

In his ruling, Agostini noted that Scheinman “repeatedly questioned” City Clerk Mazza about the validity of the signatures during the BID application process. But Mazza had ceded the job of checking those signatures against property records to Sarafin. And in the end, neither official verified the signatures — even though each officially certified that the BID had been properly formed.

Why?

“I think the biggest issue was that we had no particular guidance from anyone who wasn’t a direct proponent of the BID,” Mazza said of herself and Sarafin. “I mean, I’m not a lawyer. Joan’s not a lawyer. So, in order to make sure that we were doing things correctly according to the law, we expected that we were going to have some sort of support, to help walk us through this process. That didn’t happen, so we were basically left to figure this out on our own.”

Timeline of BID’s rise and fall

As questions arose about the signatures and other aspects of the BID application, Mazza sent an email in January 2009 to BID organizers, including Springfield attorney Jeffrey Fialky. “I’m becoming more and more concerned about the process used to reach the percentages needed and being put in the middle of this, not having very much knowledge on this issue,” Mazza wrote.

Mazza recommended that the signatures, which had already been approved by Sarafin in early December, be pulled and reviewed further in order to match them against the property records available through the assessors office.

In an email conversation submitted during trial, Fialky wrote back stating that the law made “absolutely no requirement” for this level of work on the part of the assessor.

“So, where should I have gone from there?” Mazza said. “He tells me I don’t need to worry about it, and he’s an attorney hired specifically to work on this. I’m assuming he knows what he’s talking about.”

Fialky was hired by the BID steering committee to represent the organizers throughout the petition process. He said that at the time the BID was formed, there were no applicable court cases to refer to, and that the committee interpreted the statute as best it could. “There were inherent ambiguities, and the BID incorporators used good faith to interpret them,” Fialky said.

In retrospect, Mazza said she thinks the city should have sought more outside counsel on the procedural details. “It would have been more simple if we had had more legal advice available to us.”

Sarafin has also been reflecting on these issues over the past three months. She remembers being introduced early on to Ann Burke, a BID specialist on staff at the Economic Development Council of Western Massachusetts who served as a paid consultant with the Downtown Steering Committee. Then-Mayor Clare Higgins and Dan Yacuzzo, a BID organizer who would later become its executive director, “said that she was the expert on the BID, and that she would advise us on how to accomplish this.”

Burke was present in the room, Sarafin recalled, when she and Deputy Assessor Joseph Cross met with BID organizers on Nov 19, 2008, to go line by line through the signatures and match them on a map of parcels within the district. “She was observing what we did, advising us,” Sarafin said. “I never imagined it was going to be such a mess.”

Sarafin acknowledged that certain signatures were illegible. “But we were told we just had to make sure that every parcel had a signature. And Ann Burke had told us that every single signature had permission from the owner to sign.”

The heat felt by Sarafin and Mazza during and after the trial was embarrassing, Sarafin said. “We both felt like we got thrown under the bus. When the ruling came out, I was told not to comment, but I felt that I wanted to. I wanted to stand up for myself.”

When asked about the role Burke played in the process of verifying signatures, Higgins stressed the fact that everyone involved was doing their best to interpret the relevant legislation. “I don’t think there was any evil motive from anyone,” she said. “I think it was not a very well-written law.”

Yacuzzo passed away in October.

Technically void

In an interview, Burke called Agostini’s rejection of the 63 signatures a “technicality.” When asked whether everyone said to have signed did actually sign, Burke said that “there was never a question.”

“The reality was that every single one of those signatures was obtained by a member of the steering committee with good intention,” she said. “People on the steering committee were charged with collecting signatures of specific people. It’s not like you’re standing on the corner collecting random people’s signatures.”

When critics questioned the application process as the BID was being formed in 2009, proponents voiced a similar defense.

“The BID committee did the math before presenting the final petition,” Yacuzzo told the Advocate in 2009. “Of course we did the calculations — why would we have wasted everybody’s time by presenting a petition that did not meet the requirements of Chapter 40O?” he asked, referring to the Massachusetts law for forming a Business Improvement District.

The application and its signatures, he said, were “appropriately verified and approved by the assessor and the city clerk. City Solicitor Janet Sheppard has issued a statement verifying that the BID petition meets all of the statutory requirements.” Sheppard declined to comment for this article.

In the discussion before the City Council’s initial 8-1 vote to approve the BID in March 2009, Sheppard assured councilors that both the BID application and the city’s certification met the requirements of state law, a recording of the meeting shows. More than an hour of discussion followed, covering details of the petition and what would happen once the BID was formed.

Mayor David Narkewicz was present at that meeting, serving at the time as Ward 4 councilor. Shortly before the vote, he said: “I’m fairly — I’m very — confident having met with [Mazza] that the process that she used on the signatures was sound.”

Northampton City Council approves the BID, March 2009

Councilors, including Narkewicz, spoke of their support for the initiative. They discussed how impressive it was that, despite the recession that had recently hit, Northampton had a tight group of business owners willing to come together and pay fees to ensure downtown was well-maintained.

Then-Councilor Raymond LaBarge was the only member of the council to vote no on the petition. He said the city’s contribution to the BID — $35,000 per year — would be better spent ensuring no city employees got laid off than on beautifying downtown.

“I don’t think you’ll ever live this down, Clare, because you started this,” the late LaBarge told the mayor before the vote.

Mayor Narkewicz, reflecting on that March 2009 meeting, said in a recent interview that the city made the best call they could with the information available. “To the extent that I made that statement, it reflected what had been advised. Obviously, hindsight is 20-20.”

Narkewicz described the state law regarding BID establishment as “vague,” with no case law to draw from at the time. He added that no signatories stepped forward in public hearings held in the months before the BID formation to say their intent was misrepresented.

Is this your handwriting?

So what of those property owners who initially signed the BID petition? In interviews with the Advocate, many expressed frustration and disappointment that the issue of signatures had torpedoed the BID. Some, however, said it’s just as well.

Richard Madowitz, whose signatures for 15 properties were called into question, was one of the members of the original Downtown Steering Committee.

“It shakes your faith in the judicial system when you see something like this,” he said.

Duke Corliss, whose signature was also contested, expressed his disappointment with BID opponents Scheinman and Suher. He said he felt that the plaintiffs were “purely searching for a technicality.”

Bowles, the former BID chairman, said it would have been easy to confirm his authority to sign on behalf of his downtown properties. “There’s a million places that one could go to verify that this was my signature,” Bowles said. “So I thought that whole argument was a little over the top.”

The Advocate attempted to verify signatures the judge tossed for being illegible, here’s what we found …

Not everyone who signed an assent at the time was completely sold on the BID, especially when state law shifted in 2012 to make BID fees mandatory rather than optional.

“Whether you like Eric [Suher] and Alan [Scheinman], they were right to challenge the BID,” Gordon Thorne, who signed for A.P.E. Ltd. Gallery at 126 Main St., said in a recent interview. He added that although the steering committee worked hard to secure enough signatures, he felt that the existence of the BID wouldn’t benefit him as a gallery owner. “The city should be taking responsibility for the maintenance of downtown,” he said.

Mansour Ghalibaf, who signed for two properties including the Hotel Northampton, also served on the original steering committee. He said he suspects that the 2012 law making BID participation mandatory fanned the flames of the growing dispute. “That’s what led to the demise of the BID.”

Prospective BID members had begun bailing out within a month of the BID’s formation in 2009. According to Agostini’s ruling, 60 percent of the eligible properties had taken advantage of a 30-day window to opt out as the organization was forming.

Joe Blumenthal, owner of Downtown Sounds on Pleasant Street, served on the steering committee and remained a strong BID supporter throughout the process. Blumenthal conceded that the petition had its faults. For one thing: the assent form distributed throughout the proposed district did not include a blank space requiring signatories to print their names as well.

It is clear that this simple step — which organizers of the Amherst BID took when forming their group — could have significantly improved the city’s ability to verify and defend contested signatures.

“We made mistakes and that was one of them,” Blumenthal said. “It was careless and stupid for us not to have done that.”

“In the end, I wish that people who didn’t like the idea hadn’t signed the petition,” he added. “If they had never signed it, there wouldn’t have been a BID in the first place,” he said. “If they had said they would opt out, I would have dropped out of the steering committee that day. We thought that we had more support than we did.”

Blumenthal said that the entire ordeal sapped the community of any appetite for reestablishment. The BID, he said, is “gone away, and it’s not coming back.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com and Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.

Synopsis of Downtown Strategy Proposal Jan 2015