Deshanay Gonzalez, 21, of Holyoke, stands near Ingleside Mall’s Aeropostale, rocking her nine-month-old daughter, Rose, in her stroller. “There’s plenty of opportunity here,” she says. “It’s our time. It’s time for women to take over.” Rose senses her mother’s gusto and gets excited, sitting up, laughing and flailing her arms. Gonzalez smiles down at her.

“You’re looking at the next woman president, right here,” she says.

To kick off women’s history month, online metric tracker WalletHub ranked the U.S. states in order of “best and worst environments for women,” naming Massachusetts second-best in the nation, after Minnesota. The ranks were awarded based on measurements of women’s “economic and social well-being” and health care. The silver medal begs the question: What does the second-best state for women look like in a country where, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average working woman makes 82 cents for every dollar a man earns?

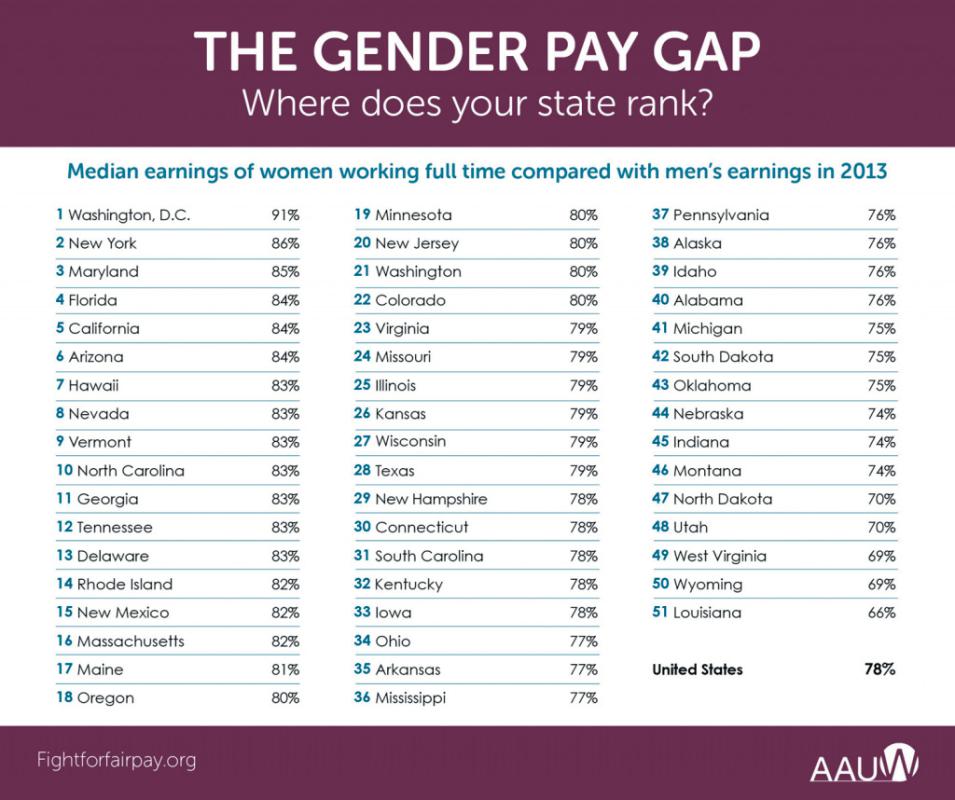

WalletHub looked at median earners with adjustments for living costs, female unemployment rates, poverty rates, share of women-owned businesses, high school dropout rates, childcare costs and availability, female voting records, pay gaps, political representation, women’s hospital ratings, uninsured rates, preventative health care for women, life expectancy, and obstetric care. The commonwealth scored such high points for quality education, insurance and obstetric care it overshadowed less glowing marks for equality and pay — Massachusetts was ranked WalletHub’s thirteenth best state for women’s equality, and the American Association of University Women’s webpage ranks Massachusetts sixteenth in the nation for the gender pay gap. The chart, which cites 2013 U.S. Census Bureau data, shows women in first-ranking Washington D.C. average 91 percent of men’s earnings, and Massachusetts women land at 82 percent.

Even though Massachusetts is one of the better states for women to live in, it’s not devoid of gender-based inequalities.

“You have this myth about Massachusetts. We’re number two. That’s great,” says Liz Friedman, program director at MotherWoman in Hadley. “And it is. But there are still a lot of women out there struggling and there isn’t a level playing field. While Massachusetts is at the head of the pack, we are not by any means ahead of the pack internationally. We’re seventeenth among 22 industrialized nations. We rank twenty-third in gender equality. Even being at the top, we’re far, far behind what’s happening in other countries.”

What creates the pay gap? The answer gets a bit tricky, but UMass sociology professor Michelle Budig says the gender pay gap has more to do with marriage and motherhood than anything else. Budig, who has testified at congressional hearings discussing the gender pay gap, says when you look at other countries who have made more progress at closing the gap, you find the differences often lie in subsidized childcare, nationally mandated paid maternity leave, and a tax system that taxes women individually, not based on their husbands’ income. Budig’s report cites Bureau of Labor and Statistics data, showing that single, childless women earn 96 percent of the man’s dollar, while married mothers make only 76 percent. The data also shows equity drops off for women over 35, the age at which many working women, who are “more apt to delay motherhood,” marry and have children. Controlling for age, women aged 25 to 34 make 90 percent of the man’s dollar, while women aged 35 to 44 drop down to 78 percent of the man’s dollar. Budig refers to the phenomena as the motherhood wage penalty. Her report states that roughly a third of the wage hit occurs because of women who reduce hours or take time away from work following the birth of a child. The remaining two-thirds of the penalty, Budig reports, are difficult to account for. The U.S. has no federally mandated paid leave policy, leaving the majority of women in a tricky scenario post-childbirth. And Budig reports “studies suggest that employers treat parents differently than childless workers, to men’s advantage and to women’s disadvantage.”

Budig and colleague Joya Misra assert that childcare is a major piece of the puzzle, as expensive childcare often puts mothers in the position where they’re choosing whether to stay at home and call it a wash, or pay for childcare with little to no profit margin. Women who leave the workforce while their children are young and then return later on miss out on valuable experience, and Budig says it proves difficult for women to recover salaries. She says subsidized childcare for children ages 0-2 is especially important for closing the gap.

“It’s actually cheaper to send your kids to college at UMass than it is to pay for childcare in Massachusetts or Maryland,” says Budig.

Misra, professor of public policy and sociology at UMass and editor of Gender and Society, says while Massachusetts has one of the best childcare systems in the country, at nearly $20,000 per year, it is also one of the most expensive. Low- and middle-income earning women, she says, are squeezed.

“It’s a progressive state — I do think we deserve to be highly rated, but I think we’d have a more complicated story if we looked at how it plays out for all women,” says Misra.

In talking with women around the Valley, I found that the responses were mostly positive.

Sarah Buttenwieser, 51, of Northampton says one great thing about the Valley is that the job market is more diverse for women here than in other places. She says she feels you’re more likely to see female farmers, police officers, or carpenters than in other areas of the country. She says there’s an “activist culture” and an overall sense of flexibility that gives her a good feeling about raising her seven-year-old daughter here. “There’s so much higher education here in general it’s a more enlightened place,” says Buttenwieser. “My daughter’s in first grade. She imagines that girls can do anything that boys can do.”

Margot Putnam, 22, a Mount Holyoke student, says her mother does manufacturing work in Holyoke and has long been the only woman at her job. She also says that because of sexual violence at local colleges, she doesn’t necessarily feel safer here than in bigger cities. “But there are fantastic female mentors in the area,” says Putnam. “And in terms of systemic misogyny, I have very limited experience with it.”

Misra hails the state’s education system. Also, she says, the state legislature has proven supportive of policies that help close the pay gap. “I live in a state where I know my work will be supported, where I know my views are often, if not always, reflected in the policies my legislators look at,” says Misra. Experts like Budig, Friedman and Misra are happy to rejoice in what Massachusetts is doing right — that’s why they live here and not in Arkansas, which was ranked last on WalletHub’s list — but they maintain that closer inspection reveals a grainier reality.

“We talk about the impact of sexism,” Friedman says of her children. “They drink this with their Cheerios and milk in the morning — the understanding of the world we live in. I tell my daughter what most mothers tell their daughters — I’ll cheer you on no matter what you do, but there are forces in the world who will make it difficult for you.”•

Contact Amanda Drane at adrane@valleyadvocate.com