My parents immigrated to the United States from Australia, arriving in New York Harbor in the 1960s, and settling in a town on the Hudson River. Unlike people of other nationalities who choose to make a new life in America, my parents did not bring with them a burning desire for me and my brother to be schooled in the ways of their people.

My mom was a fantastic cook, but the meals she made us were far more influenced by her European travels or watching Julia Child than by her own upbringing in an outback town in southern Australia. We usually had a leg of lamb for Christmas dinner, and there was always a jar of Vegemite around, but I never did hear my parents reminisce about a quintessential Australian meal they missed. The few traditions we followed were ones that previous ancestors had brought to Australia from England, and it was difficult to discern culinary styles that were distinctly Down Under.

While I never learned a particular entree made from native ingredients, I’ve come to realize rather than fancy dress-up meals, Aussies distinguish themselves with comfort foods. Instead of a suit and tie, the Australian national cuisine should be consumed in slippers and sweats. For example, consider the following recipe, which in many ways acts as a fundamental building block for many other delicacies from the land beneath the Southern Cross.

Beans on Toast

Ingredients:

1 can of baked beans

(For a zesty Italian alternative, try a can of spaghetti)

2 slices white bread

Margarine

Vegemite (optional)

Equipment: Saucepan, toaster, plate, knife and fork

Instructions: When beans begin to boil, turn down to a simmer and begin toasting the bread. When complete, place toasted bread on plate, add butter and Vegemite (optional), and then pour beans over the toast. Eat with a knife and fork.

(Those trying Vegemite for the first time, please use caution. Try a small amount first before venturing further. It’s not peanut butter. Think of the pungent, salty substance as wasabi for bread and you’re less likely to get hurt.)

The position of the toast is critical: never place it to the side of the food, but always underneath the beans or other meal substance.

In America, toast is generally only served with breakfast, and often with a choice of jams or jellies. Given enough bread, Australians will eat toast with every meal, and while they will occasionally eat marmalade with their breakfast tea, they generally prefer swarthier condiments rather than anything berry-based.

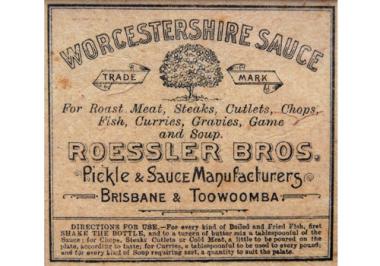

Toast is seldom enjoyed on its own, but as a vehicle for the course proper. It’s something to stick your fork into when whatever stewed slop you’ve poured on to it (stew, chili, sloppy joe, etc.) isn’t substantial enough to make it from plate to mouth. If toast is eaten for breakfast by an Australian, it generally appears beneath the eggs, ready to sop up the runny yoke and any Worcestershire sauce that’s happened to mingle with it.

*

This particular Australian passion for simply prepared comfort foods has been noted in two works on the subject of Down Under culinary arts: Possum Magic by Mem Fox and The Magic Pudding by Norman Lindsay.

Both are popular children’s books in Australia (the former is better known to American audiences), and each uses traditional foods as critical plot elements. In a search to find the ingredient that will make a young possum visible again, Possum Magic reminds us of pavlova and lamingtons, two desserts that are supposed to have come from Down Under (though some believe the meringue-based pavlova was originally from New Zealand).

The Magic Pudding introduces a band of traveling pudding-owners who have in their possession a “cut-and-come-again pudding” that instantly renews itself once eaten. This isn’t a pudding Bill Cosby would be at all familiar with. Not chocolate or vanilla, this is a steak-and-kidney pudding (or any other variation on that theme). The pudding’s name is Albert, and he’s an ornery sort whom the owners need to keep an eye on. Nothing captures the Australian passion for simple food pleasures like the antics of the pudding-owners as they try to save their prize from repeat attacks by notorious pudding thieves.

While we only had meat-based puddings for Christmas, when my mom’s mother visited us, she always spent a weekend making many freezer bags full of meat pasties. Like meat pies, these are a doughy envelope of pastry containing cooked meat and vegetables, which, when heated up, taste great with Worcestershire sauce. And, as you might have noticed, pasties are not altogether unlike beef stew on toast.

*

When I told my father, who has since returned to Australia, that I was working on a piece about the cuisine of his people, his first question back was, “Are you serious?” When I assured him I was only slightly serious, he first reminded me that a lot had changed in Australia since he’d left it to raise a family in America. Different foods and ethnic influences were around that weren’t there when he’d been a child during the Depression and war years; the country had even produced a number of world-class chefs in recent times. He reminded me of the booming Australian wine industry.

But when I argued that toast seemed to me to be a cornerstone in the foods of his people, he laughed and had to admit that toast probably hadn’t yet lost its position of eminence. “And those American toasters!” he said, remembering. “So hard to get a serious toaster in America.”