Three early-season productions have at their hearts a quest — for a lofty ideal; for an escape from bondage; for a job, any job. All three quests are in some sense foolhardy — desperate pursuits of a shimmering grail. But all are, in their very different ways, utterly heroic.

Man of La Mancha, at Barrington Stage Company through July 11, embodies that idea most explicitly. Indeed, its most famous song was originally titled “The Quest.” Although most people think of this show as “a musical version of Don Quixote,” the title character isn’t really the hero of Miguel de Cervantes’ picaresque novel, but the author himself.

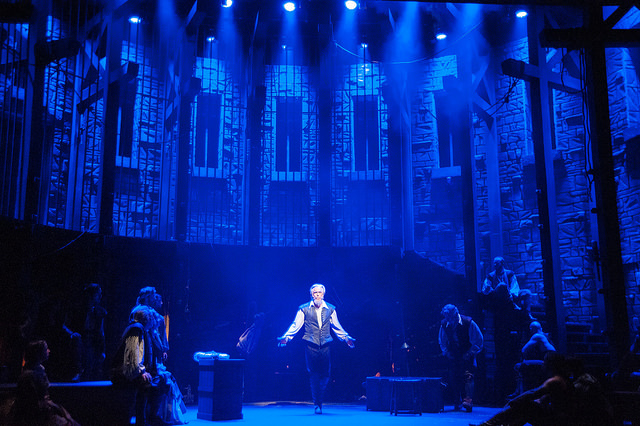

The genius of Dale Wasserman’s witty, muscular script is its play-within-a-play structure and its conspicuously non-fanciful setting: not the sunlit fields of quixotic adventures but a squalid dungeon of the Spanish Inquisition, where Cervantes is awaiting trial for perceived insults to the Church. (James Kronzer’s set is a towering sepulchral vault of gray rock, artfully lit by Chris Lee.) Quixote’s story is performed as a jailhouse “charade” enacted by the prisoners, with Cervantes himself playing the would-be knight errant.

The genius of Dale Wasserman’s witty, muscular script is its play-within-a-play structure and its conspicuously non-fanciful setting: not the sunlit fields of quixotic adventures but a squalid dungeon of the Spanish Inquisition, where Cervantes is awaiting trial for perceived insults to the Church. (James Kronzer’s set is a towering sepulchral vault of gray rock, artfully lit by Chris Lee.) Quixote’s story is performed as a jailhouse “charade” enacted by the prisoners, with Cervantes himself playing the would-be knight errant.

Man of La Mancha is a very good play but not, in this critic’s opinion, a great musical. It’s an invigoratingly theatrical piece of theater, inspired by Brecht and experimental theater of the sixties (this year is its 50th anniversary), in which the play-within-the-play is created by its own audience from found objects, and the framing device becomes a kind of anti-metaphor for the story it contains.

Joe Darion’s lyrics are supple and often clever, but most of Mitch Leigh’s Spanish-flavored score is no more than workmanlike. There’s one exception, of course: “The Impossible Dream,” the iconic anthem that perfectly captures the show’s spirit and message, and even now transcends the clichéd cabaret-fixture moss that has grown around it.

Julianne Boyd’s production finds every beat in the show’s hopeful heart, every laugh in its antic moments and every pang in its dark side, never reaching for pathos. It’s brisk (one long act), crowded (a cast of 20) and energetic, with lively movement choreographed by Greg Graham and balletic brawls staged by Ryan Winkles, as well as a horrific rape sequence (yes, children, this is not The Sound of Music).

Jeff McCarthy’s Cervantes is ironic and resourceful — a philosopher-showman — and his Quixote, created from false whiskers and a breastplate from a prop trunk, is a picture of moral vigor in an enfeebled frame. McCarthy is an arresting stage presence and a strong singer, though his rendition of “The Impossible Dream,” at first nicely understating the familiar cadences, then blows up into an unnecessarily over-the-top climax.

Jeff McCarthy’s Cervantes is ironic and resourceful — a philosopher-showman — and his Quixote, created from false whiskers and a breastplate from a prop trunk, is a picture of moral vigor in an enfeebled frame. McCarthy is an arresting stage presence and a strong singer, though his rendition of “The Impossible Dream,” at first nicely understating the familiar cadences, then blows up into an unnecessarily over-the-top climax.

Tom Alan Robbins’ Sancho Panza, bemused squire to the mad don, is simple but no simpleton, “a fat little bag stuffed with proverbs,” amusing and compassionate — though the salute to their comradeship, “I Really Like Him,” is a bit too cute and fey for the play’s rather gritty tone.

Plenty of grit is provided by Felicia Boswell as the scullery maid and town whore who’s cast as the fair damsel Dulcinea, object of Quixote’s romantic chivalry. She’s an unwilling ingénue, her bleak, dirty life at odds with the old gentleman’s chaste fantasy, and Boswell’s performance wraps a slave’s resentment around a wildcat’s temper — though the song in which she displays both of those is delivered at such an unvarying pitch of screaming rage that it undercuts its own power.

Plenty of grit is provided by Felicia Boswell as the scullery maid and town whore who’s cast as the fair damsel Dulcinea, object of Quixote’s romantic chivalry. She’s an unwilling ingénue, her bleak, dirty life at odds with the old gentleman’s chaste fantasy, and Boswell’s performance wraps a slave’s resentment around a wildcat’s temper — though the song in which she displays both of those is delivered at such an unvarying pitch of screaming rage that it undercuts its own power.

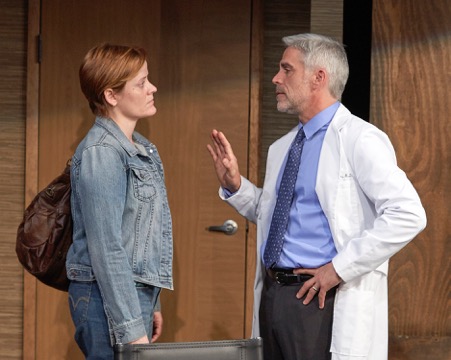

The unlikely quest at the center of David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People, at Hartford’s TheaterWorks through June 28, is far more prosaic but just as courageous and perilous as Don Quixote’s illusory exploits. After she’s fired from her dead-end job at the dollar store, all Margie wants is another job, a means of paying her rent and supporting her disabled daughter.

Already running just to keep in place, and now at the end of her resources, both financial and emotional, she appeals to an old boyfriend from the neighborhood — working-class South Boston — who has gotten out and now has Dr. in front of his name and a swank house in Chestnut Hill.

Already running just to keep in place, and now at the end of her resources, both financial and emotional, she appeals to an old boyfriend from the neighborhood — working-class South Boston — who has gotten out and now has Dr. in front of his name and a swank house in Chestnut Hill.

Lindsay-Abaire grew up in Southie, and his play is a dissection of the class divide that infects our supposedly classless society. Intentionally, I’m sure, he makes us middle-class theatergoers more uncomfortable in the scenes in the doctor’s upscale office and home than in Margie’s proletarian kitchen and the church Bingo hall. These scenes are more discomfiting to the characters, too, as Margie embarrasses both herself and her hosts in those glossy surroundings where privilege rests, as often as not, on luck.

And luck is the theme the play rests on as well. Was it pure luck that got Mike out of Southie, or, as he insists, hard work and good choices? — which Margie, he implies, failed to make. Turns out it’s both luck and opportunity, for she has a secret or two she’s loath to spring on him, because he’s “good people,” as she says, and she is, too.

The play asks tough questions laced with laugh lines. The playwright has seeded his dialogue with what he has described as “a very dark working-class sense of humor that everyone in Southie seems to possess — often inappropriate, brutally honest and painfully funny.” And Rob Ruggiero’s bracing production uses that humor to puncture pretenses and nail home truths.

The play asks tough questions laced with laugh lines. The playwright has seeded his dialogue with what he has described as “a very dark working-class sense of humor that everyone in Southie seems to possess — often inappropriate, brutally honest and painfully funny.” And Rob Ruggiero’s bracing production uses that humor to puncture pretenses and nail home truths.

None of the smart, strong cast completely masters the Southie accent, but Erika Rolfsrud, as Margie, totally inhabits the body language and smart-aleck sass, along with a steely determination that drives her to reckless acts. She’s ably abetted by Megan Byrne as her comically acerbic best friend, Audrie Neenan as her crabby old landlady, Buddy Haardt as her kindly ex-supervisor, R. Ward Duffy as the conflicted Southie escapee, and Chandra Thomas as his sleek, African-American wife.

And that last part is a puzzle. Lindsay-Abaire has made the character black and sympathetic and sophisticated, far classier than the white woman who comes calling, and then does nothing with that inevitable tension — especially in the context of South Boston, where de facto segregation persists and creeping gentrification is reigniting old resentments.

And that last part is a puzzle. Lindsay-Abaire has made the character black and sympathetic and sophisticated, far classier than the white woman who comes calling, and then does nothing with that inevitable tension — especially in the context of South Boston, where de facto segregation persists and creeping gentrification is reigniting old resentments.

But Margie seems utterly unphased by the mixed marriage, and Thomas’s performance makes the woman as elaborately insincere toward her uninvited guest as any white liberal scrambling to establish nonracist bona fides with a person of color. That, and the tension between the married couple — which we have to guess arises from their own class differences — never blend believably into the playwright’s mix of class commentary.

The title character in Butler, which opened the season at Barrington Stage’s studio theater, is a Civil War general torn between duty and conscience. But the quest in this play belongs to a fugitive slave who has escaped from a Confederate garrison in Virginia and fled to a Union fort seeking — no, demanding — sanctuary.

Richard Strand’s remarkable drama is based on a little-known but decisive incident in the early days of the war — one that changed the terms of “the slavery question” in the conflict and, in some ways, its outcome.

The general is Benjamin Franklin Butler, a Massachusetts lawyer who has been a commanding officer in Lincoln’s army for less than a month. The slave is Shepard Mallory, fiercely determined, alarmingly articulate and beyond desperate. Butler is bound by the Fugitive Slave Law to turn the man back to the Confederates, but he knows that would be a death sentence.

The general is Benjamin Franklin Butler, a Massachusetts lawyer who has been a commanding officer in Lincoln’s army for less than a month. The slave is Shepard Mallory, fiercely determined, alarmingly articulate and beyond desperate. Butler is bound by the Fugitive Slave Law to turn the man back to the Confederates, but he knows that would be a death sentence.

The play is a battle of wits, not just between the two men, but between legal imperative and lawerly ingenuity. And Butler has his own quest: to unknot the conflict between obligation and compassion.

Notwithstanding the title, the thrust of the play is as much Mallory’s as Butler’s, and notwithstanding their wildly unequal status, the men are surprisingly similar. Both are smart, peremptory, quick to anger, self-assured and self-possessed — qualities that drive their relationship and the play itself.

Joseph Discher’s taut production featured a perfectly matched pair of lead performances — David Schramm’s Butler ironic, even playful, but never far from apoplexy; Maurice Jones’ Mallory sardonic, infuriating, proud to the point of arrogance, with the quiet courage of a man who has staked everything on an impossible gamble and has nothing to lose but his life.

PS — If you missed this play in Pittsfield, you can catch it this winter in West Springfield, where it will be part of the Theater Project’s 30th-anniversary season.

Barrington Stage photos by Kevin Sprague; TheaterWorks photos by Lanny Nagler.

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com