By cosmic coincidence, three shows now playing in the Valley and Berkshires feature three guys named Henry: Henry the Fifth, king of England; Henry David Thoreau, lord of Walden Pond, and Henry Antrobus, bad-boy son of the world’s first couple, whose real name is … Cain.

All three also continue this week’s ghost theme, as each man is haunted by his own or others’ past actions.

Shakespeare’s Henry V (theater wags like to call it Hank Cinq) picks up where his Henry IV duology ends, with a young monarch trying to live up to his dead father’s kingly stature and live down his adolescent reputation as a reckless wastrel. Both specters hang heavy on the ermine as he embarks on a military adventure aimed at legitimizing his crown by conquering some French territory.

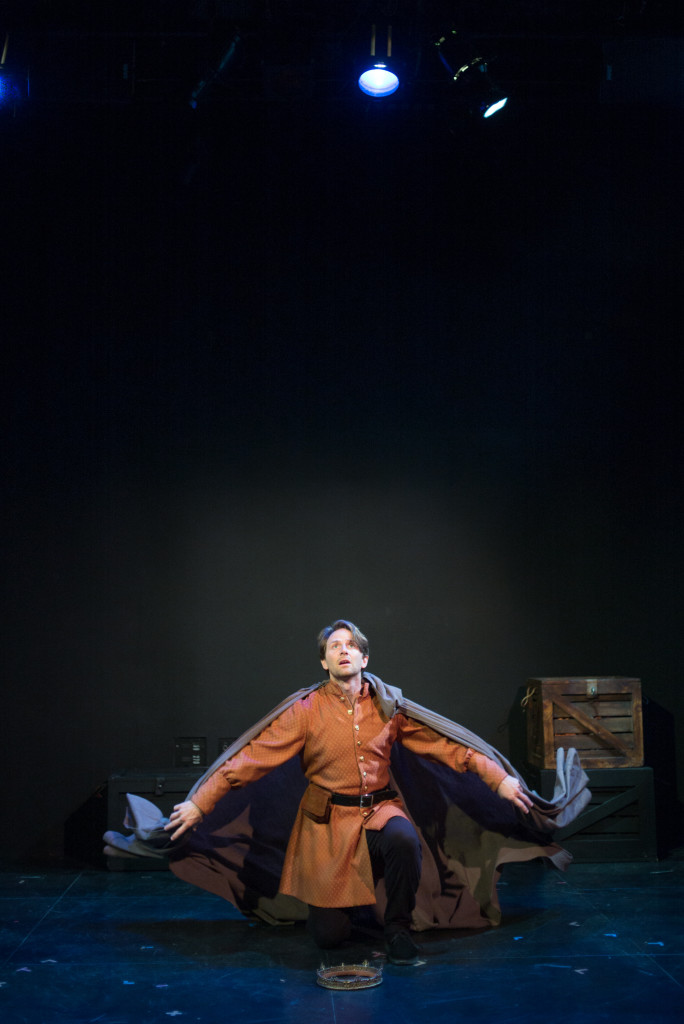

Henry V, running till August 23rd at Shakespeare & Company, is perhaps the perfect play for the troupe’s “Bare Bard” productions: condensed, small-cast renditions with basic sets and props and everyone playing four or five parts. After all, the play’s first words invite us to let our “imaginary forces” work to fill “the vasty fields of France” with soldiers and horses. Here, when Ryan Winkles, as King Henry, calls his depleted army “we few, we happy few,” he’s not being modest: There are only seven people onstage with him.

That approach works beautifully in the “perilous narrow” confines of the intimate Bernstein Theatre, where we sit within touching distance of the performers – and where the actors’ gaze regularly expands to include us, the audience, as soldiers, courtiers, barflies. In Jenna Ware’s continuously imaginative staging, the ensemble move smartly through their protean roles, spicing swift shifts of mood and setting with a-capella singing (original music by Andy Talen) and changing, often before our eyes, into new characters and costumes (doublets and gowns, by Govane Lohbauer, over identical black trousers). The energy is electric, and there are some breathtaking stage images – a shadowy abstraction of the climactic battle, a colorful scatter of cloaks representing the battlefield dead.

That approach works beautifully in the “perilous narrow” confines of the intimate Bernstein Theatre, where we sit within touching distance of the performers – and where the actors’ gaze regularly expands to include us, the audience, as soldiers, courtiers, barflies. In Jenna Ware’s continuously imaginative staging, the ensemble move smartly through their protean roles, spicing swift shifts of mood and setting with a-capella singing (original music by Andy Talen) and changing, often before our eyes, into new characters and costumes (doublets and gowns, by Govane Lohbauer, over identical black trousers). The energy is electric, and there are some breathtaking stage images – a shadowy abstraction of the climactic battle, a colorful scatter of cloaks representing the battlefield dead.

So it’s puzzling why some parts of the production work against its own creative flow. It’s not until the second half that the show really finds its feet. In fact, the two sides of the intermission feel almost like different productions.

S&Co does a presentation called Shakespeare and the Language that Shaped a World, a high-energy introduction to Shakespeare created for schools and also playing for the public this summer. The first half of this Henry V reminded me of that approach: the language overly emphatic, the comedy overbroad, as if making doubly sure we “get it.”

The Chorus here is a real chorus – five actors speaking contrapuntally, a nice change-up, but their delivery is as ponderous as a sermon. The tavern scenes with the Prince Hal’s old drinking buddies are so manic that the jokes and slapstick barely raised a chuckle when I saw it.

Winkles is the only cast member with just one role, and he’s marvelous. From the start, he’s grounded and natural, finding a perfect balance between steely determination and wry self-awareness. His two big speeches rallying the troops are powerfully understated, and his wooing of the French princess – a coy but feisty Caroline Calkins – is the sweetest and funniest version of that scene I can remember.

Winkles is the only cast member with just one role, and he’s marvelous. From the start, he’s grounded and natural, finding a perfect balance between steely determination and wry self-awareness. His two big speeches rallying the troops are powerfully understated, and his wooing of the French princess – a coy but feisty Caroline Calkins – is the sweetest and funniest version of that scene I can remember.

The ensemble in almost every case illustrate that first-half/second-half split. For example, Jonathan Croy, David Joseph and Jennie M. Jadow, as tosspots Pistol, Nym and Bardolph, ham it up shamelessly in the tavern scenes; but then Croy also becomes a poignantly crippled French King, Joseph an amusingly snooty Dauphin, and Jadow the princess’s starchy lady-in-waiting.

Henry David Thoreau, the Transcendentalist philosopher-contrarian, famously turned his back on civilization and lived for a time beside Walden Pond near his hometown of Concord, Mass. He’s also remembered as having spent a night in jail for refusing to pay his taxes to protest American imperialism and slavery.

What’s not as well known is his outspoken support of John Brown, hanged in 1859 after his failed attempt to foment an armed slave rebellion in Virginia. Brown’s soul, as we know, went marching on, and it’s his spirit that hovers around Thoreau in the fascinating but flawed one-man show now premiering in the Berkshire Theatre Group’s Unicorn Theatre.

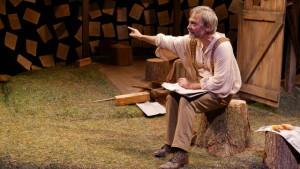

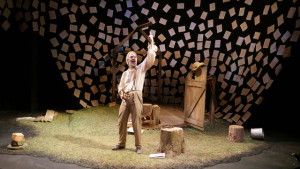

Thoreau or, Return to Walden, written and performed by popular BTG star David Adkins, draws much of its 100-minute monologue from three of Thoreau’s works: Walden, that hymn to simplicity and gratitude; Civil Disobedience, a precursor of Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail; and A Plea for John Brown.

Thoreau or, Return to Walden, written and performed by popular BTG star David Adkins, draws much of its 100-minute monologue from three of Thoreau’s works: Walden, that hymn to simplicity and gratitude; Civil Disobedience, a precursor of Martin Luther King’s Letter from Birmingham Jail; and A Plea for John Brown.

We find Thoreau on the morning of Brown’s execution, revisiting his cabin in the woods (Michael J. Riha’s rustic set is backed by a cyclorama of manuscript pages). He splits a log, marvels at a tiny ant traversing his finger, and shares with us a winding train of thought about, well, the whole purpose of life.

Thoreau is what a friend of mine calls “a passion piece” – a project that grows out of a deep need to express something vital. In a program note, Adkins explains that the seed of this piece came to him during a sad, solitary time in, yes, an isolated cabin in the New England woods. His passionate personal connection to the material and its message is what’s wonderful about the piece, but also what weakens it. Playwright Adkins wants to share so much of Thoreau’s wit and wisdom that the piece gets too dense to properly follow and appreciate.

But actor Adkins’ performance, under Eric Hill’s sensitive direction, is jaw-dropping. This Thoreau is no slightly eccentric gent but a thoroughgoing radical with an unapologetic urgency and crazy eyes. He seems almost to be channeling Brown: “My thoughts are murder to the state.”

But actor Adkins’ performance, under Eric Hill’s sensitive direction, is jaw-dropping. This Thoreau is no slightly eccentric gent but a thoroughgoing radical with an unapologetic urgency and crazy eyes. He seems almost to be channeling Brown: “My thoughts are murder to the state.”

Brown was considered a dangerous lunatic, and not a few of Concord’s staid citizens found Thoreau a bit touched. But who are the crazies and who the sane in a society where some people are property? Brown, he recalls, was said to “throw his life away” with his rash rebellious act. Thoreau, however, considers it an inspiring sacrifice, which makes him ask himself – and most definitely us as well – “Which way have you thrown yours?”

Now in its second year, Silverthorne Theater Company is the Valley’s newest and, from the evidence, most adventurous summer fixture. The three-play season is intriguing and challenging: a world premiere, an edgy biracial comedy, and for starters, a sprawling allegorical epic.

That one, Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth, plays through this weekend in the Sloan Theater at Greenfield Community College. It’s a big, boisterous play with a large cast (I count 16 named roles plus extras) and a lot on its mind. It’s being performed, miraculously, in the summer’s smallest venue with a cast of eight and no set. The fact that it works, and works splendidly, is due largely to director Toby Vera Bercovici’s inspired use of the space and playful interaction with the material – shades of S&Co’s Henry V on a much smaller budget.

Wilder wrote the play in 1942 as a whimsical, sardonic tribute to the indomitable human spirit that was supposed to get us through the war. It’s the story of a typical suburban New Jersey family, the Antrobuses – except Act One takes place in the Stone Age, Mr. and Mrs. have been married for 5,000 years, and son Henry (remember?) is troubled by the guilt of having slain his brother. In other words, the Antrobuses are both the Typical Family and the Original Family.

Wilder wrote the play in 1942 as a whimsical, sardonic tribute to the indomitable human spirit that was supposed to get us through the war. It’s the story of a typical suburban New Jersey family, the Antrobuses – except Act One takes place in the Stone Age, Mr. and Mrs. have been married for 5,000 years, and son Henry (remember?) is troubled by the guilt of having slain his brother. In other words, the Antrobuses are both the Typical Family and the Original Family.

Wilder not only toys with time and history here, but monkeys with theatrical conventions. The family’s maid, Sabina (Linda Tardif, playfully sexy) starts the proceedings by breaking the fourth wall to address the audience, then quickly breaks character to give us her (low) opinion of the play. The playwright and director keep us similarly off balance throughout. Act Two takes place at a convention of the Fraternal Order of Mammals in Atlantic City, where a boardwalk fortune teller (a sultry Audrey Jacinthe Connor) cryptically assures us that the past is trickier to predict than the present. In Act Three, the family emerges from the rubble of war and the play takes another tradition-smashing leap.

Michael Bird is Mr. Antrobus, the very model of the genial father-knows-best patriarch. As Mrs. A., Susanna Apgar strikes a nice balance between the supportive spouse and the tigress determined to claw her way through history’s disasters. Connor Paradis is appropriately moody and rebellious as haunted Henry, and Annalise Cain finds comic nuggets in the underwritten role of his bratty teenage sister.

Michael Bird is Mr. Antrobus, the very model of the genial father-knows-best patriarch. As Mrs. A., Susanna Apgar strikes a nice balance between the supportive spouse and the tigress determined to claw her way through history’s disasters. Connor Paradis is appropriately moody and rebellious as haunted Henry, and Annalise Cain finds comic nuggets in the underwritten role of his bratty teenage sister.

The play’s shifting planes of reality and the production’s bare-stage presentation are reflected in the multitasking props, from an Our Town stepladder to a length of flexible foil ducting that becomes a mammoth’s trunk, a judge’s powdered wig and an accordion. While Bercovici and her actors make ingenious use of the entire room, from floor to catwalk, they’re hampered by its lecture-hall origins and unnecessary barriers between audience and actors. With a little investment and renovation, the Sloan Theater has the potential to be an attractive and valuable performance space in this venue-starved Valley.

Henry V photos by John Dolan; Thoreau photos by John Dolan; Skin of Our Teeth photos by Matt Burkhartt.

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com