Eleanor Cresson, a mental health and substance abuse clinician who recently went on strike from nonprofit Clinical Support Options, has worked in the field of mental health for more than 20 years and has two masters’ degrees. Despite her experience and qualifications, she said her job doesn’t provide benefits like health insurance or paid vacations. Even when she does take an unpaid vacation, Cresson said, she ends up working anyway in order to meet unwavering productivity quotas — spending at least 22 hours a week with clients. Otherwise she has to make up those hours in the weeks before and after her “time off.”

She said her wages barely bring her above $30,000. And she’s not even sure she made that much in 2014, considering the time she took off to recover from a knee injury and the many appointments clients didn’t show up for, a situation for which clinicians do not get paid.

“It sounds good when they tell you we make $36 an hour, but that’s spin and you’re not really hearing what goes into that,” Cresson said, explaining that for every paid hour spent with a client, clinicians put in another unpaid hour of paperwork.

Cresson was one of about 125 people striking outside agency sites in Northampton, Springfield, Greenfield, Athol, and Pittsfield for three days this summer. The strikers’ complaints are hardly unique. Across the U.S., workers are being asked to work harder for less pay and fewer benefits.

Unions often consider big-box corporations to be the biggest offenders of workers’ rights — perhaps simply because they employ so many — and it turns out a local CVS is no exception. Employees in the Valley were asked repeatedly this summer to surrender their meal break rights.

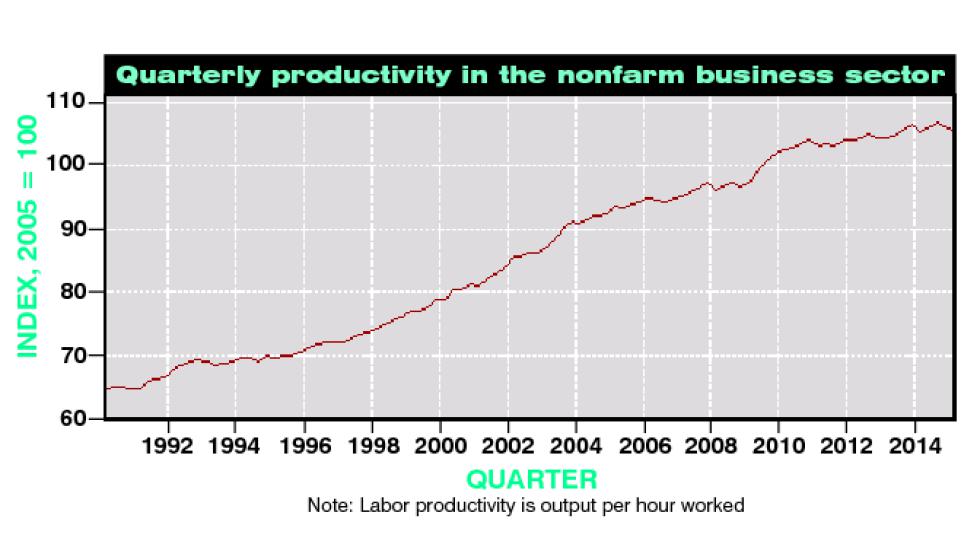

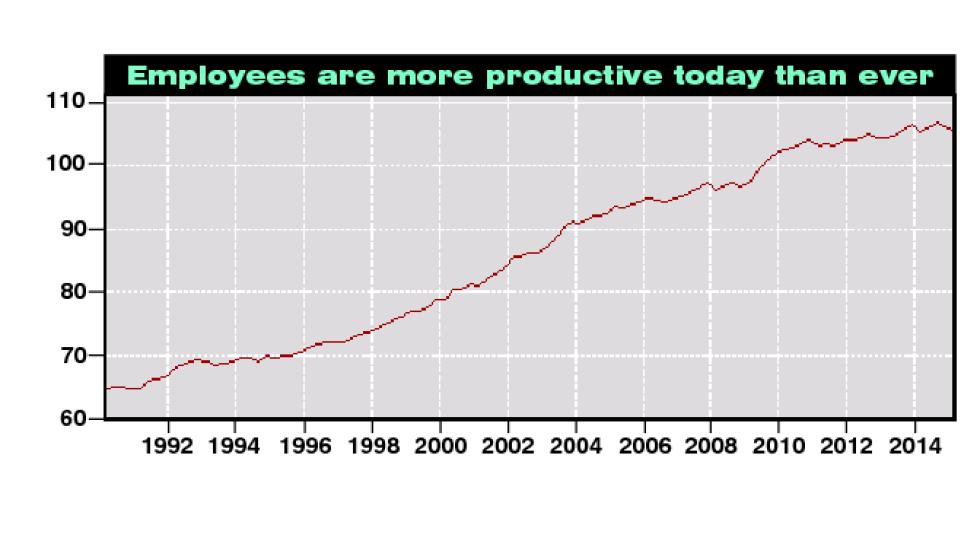

The International Trade Union Confederation released a report in spring 2014 that ranked countries by their handling of workers’ rights. The U.S. earned a four — one being the best — joining the ranks of Thailand, Indonesia, and Kuwait. As the American conversation centers around driving the economy, the average American worker is put under increasing pressure to work harder, but according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, productivity — measured in worker output per labor hour — has risen dramatically in the years since 1992.

“What’s happening in the American workplace is inconceivable for most people who came through work in the 1950s and 1960s,” said UMass Amherst professor of labor studies and sociology Tom Juravich. “Basic rights like lunch — they were ordinary across a wide swath of America. What we’re seeing is the degradation of work and the degradation of workers’ rights.”

Juravich said workers’ rights are undermined in efforts to improve the bottom line, but that such a “low-road approach” will not lead to economic prosperity. Rights missing here in the U.S. are considered birthrights in European countries, he said. For example, most European countries require employers follow due process before firing an employee, whereas in the U.S. most employment is at-will. Paid leave for new parents is also something many Europeans consider a given, and many countries also cap weekly working hours at 35 to 45 hours; U.S. federal law does not mandate paid leave for families, nor does it place any limitations on working hours for employees.

“We’re really the outlier,” he said.

Cresson said she’s worked for the mental health agency since before CSO purchased it five years ago, and conditions have only gotten worse for employees since the takeover.

“If a client doesn’t show we don’t get paid,” said Cresson, adding that the work put in by her and other clinicians is critical to Opioid Task Force efforts. “I’ve been doing this for over 20 years and I keep getting poorer and poorer. Meanwhile, the CEO is making $220,000 a year.” That’s $189,337 in salary and $28,871 in benefits, according to CSO’s tax returns.

While CSO executives say the proposed new contract is the best it can be and is industry-leading, a spokesperson for the Massachusetts Union for Human Service Workers — the union representing the group — Jason Stephany said the model is not sustainable, that the high turnover rate reflects how employees are treated. And a high turnover rate is “terrible for the clients,” Cresson said.

“We’re not here to get rich,” said another striker Stephanie Agnew, 36, of Northampton, asserting the strike came down to respect.

Sometimes the affronts to employee dignity can be found in a lunch break — or a lack of one.

At the CVS pharmacy chain, employees are asked if they will voluntarily give up their regular lunch breaks. Signing the waiver means relinquishing rights to a meal break, which state law says must be 30 minutes for employees working more than six consecutive hours and requires employees be “relieved of all duties” and “be free to leave the workplace.”

“[The manager] kept repeating how the form doesn’t mean anything,” said a local CVS employee, who asked to remain anonymous for fear of losing his job. “I was intimidated and felt in danger of being fired if I did not just give in to my nervousness and sign.”

Michael DeAngelis, a spokesperson for CVS, said the form is not isolated to local stores — it is part of the national chain’s Voluntary Meal Break Waiver program.

“Eligible employees who choose to sign this waiver are paid for working through their meal breaks and they are still provided the opportunity to eat while at work,” he said in a statement responding to an Advocate question. “The program was implemented because employees made it known that many of them prefer not to take an unpaid meal break.”

But the employee said he was pressured to sign the voluntary waiver. The employee was repeatedly asked to sign the waiver over a period of weeks, with corporate officials unknown to the employee calling him to convince him to sign. The employee said, “I believe I’m doing the right thing” by not signing the waiver, though he fears corporate retaliation.

I asked CVS Easthampton employees whether they’d been asked to sign the waiver as they headed into work one morning. One employee confirmed that he had, before two other employees came outside and told me no one else would be talking to me that day and that I might as well leave.

Recently retired CVS employee Eddie Morales remembers the pressure to give up breaks. He worked for CVS as a floating pharmacist for about seven years in the area. Though he was based out of Hartford, he served as a traveling pharmacist and worked in about 90 different CVS stores, Morales said. Uniformly, he witnessed how strict productivity quotas — answering calls and counter customers within 15 seconds, requiring pharmacists to move 40 percent of their customers to ReadyFill, CVS’ automatic refill program, for example — were preventing pharmacists from taking meal and bathroom breaks.

“You’re allowed to take a lunch break — that’s what they tell you,” Morales said. “But what they don’t tell you, especially with the key performance metrics involved, you’re still going to get penalized for that. When performance scores go down, you get written up for things falling behind.”

Since his retirement, Morales has been working with the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers to get CVS pharmacists to unionize.

“This is a story that really, really needs to be told,” he said.

When asked about the waiver, Bill Newman, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s western Massachusetts office and a spokesperson for the commonwealth’s Executive Office of Labor and Workforce Development, initially said the waiver appears to be in violation of state laws. But after examining legislation dictating meal break rights, he said, it seems CVS executives operated within the law — as long as they didn’t pressure employees to sign waivers.

“It cannot be coerced from the employer,” Newman said of signing waivers. “It cannot be anything other than genuinely voluntary.”

State law says employees are permitted to “voluntarily give up” the required break “at the request of the employer.” Jillian Fennimore, a spokesperson for the state’s Attorney General’s Office, said coercion to sign voluntary waivers constitutes a violation of state laws and employees can file complaints with the Fair Labor Division.

In the case of the CVS lunch break waiver, how “voluntary” is the response to repeated requests for compliance from an employer? In general, workers do what their bosses ask of them — because most employees want promotions, higher wages, prime hours, and to keep their jobs.

“There has not been a time in this generation that workers’ rights have been so challenged,” Juravich said.•

Amanda Drane can be contacted at adrane@valleyadvocate.com.