Pittsburgh playwright Tammy Ryan was picking up her daughter from kindergarten in 2007 when she noticed the mother standing next to her, dressed in military fatigues and combat boots. They had met the week before. Now, she was leaving for a nine-month deployment.

“I really couldn’t wrap my mind around somebody doing that,” Ryan remembers. “It made me think about the special sacrifices that mothers make when they go to war.” Ryan decided to write a play about a Marine who leaves her young son behind for Iraq, where she grapples with the effects of war, sexual trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder. A local production of that play, Soldier’s Heart, will run at the Academy of Music in Northampton Sept. 18-20.

It will be followed later in the month by an unaffiliated, but well-timed, production of a new multimedia show called The Draft, by Peter Snoad, which depicts the true stories of 10 young Americans and their responses to the military draft during the Vietnam War. The Draft, which is on tour, runs for one performance only on Sept. 27.

Soldier’s Heart offers a fictional account of the familial sacrifices we make in modern wartime, while The Draft seeks to record and honor the real-life stories of men and women in the Vietnam era, many of whom live locally in Western Mass.

But both shows are interested, first and foremost, in painting a human portrait of the chaos of war.

Soldier’s Heart

“The big stumbling block was giving myself permission to write about the military,” said Ryan, whose father served in the Navy, but who has not served herself. “I wanted to get the details right, but I didn’t want to pull any fancy tricks. I wanted the story to be honest and straight-forward.”

Soldier’s Heart takes place in 2004 and centers on a Marine sergeant named Casey Johnson, whom Ryan said grew out of “a composite of many women, and also a part of myself.” In Iraq, she faces harrowing periods of combat, as well as a sexual assault perpetrated by a fellow Marine. After returning home to Pennsylvania, she struggles to reintegrate with her family and assume a healthy post-war life.

Some of the male characters in Casey Johnson’s life are complicit in her rape, while others want to help her. Ryan said she has worked to find “a bit of humanity” in every character and still hold them — and the military — accountable for a culture in which sexual violence often goes unprosecuted.

Robert Freedman, the director of the show, said Ryan has created “incredibly vivid characters.” Behind this drive for accuracy, he explained, is an interest in fairly portraying people who are attempting to impose some structure on lives that brim with complicated, conflicting emotions.

“The theme of betrayal is strong here,” he said. “People are usually assaulted by people they know. But even after that, the whole system can let them down. How does somebody come out on the other side of that?”

Freedman is delving into this question with Northampton actor Myka Plunkett, who plays Casey Johnson. Plunkett said that stepping into the life of Casey Johnson has been “very taxing,” and that simulating the traumas inflicted on her character has been affecting her physically.

“The dissociation and alienation that Casey feels — for me, it’s manifested in my appetite,” she said, “and I’ve had a harder time sleeping since taking the role.” But reckoning with the effects of violence is a major route to empathizing more with soldiers — something that Plunkett, who has several relatives in the military, strongly believes in.

“Saying ‘the military is bad’ is a dangerous stance to take,” she said. “It makes vets and their families feel unwelcome to give voice to their struggles. I want to do my part to change that.”

The Draft

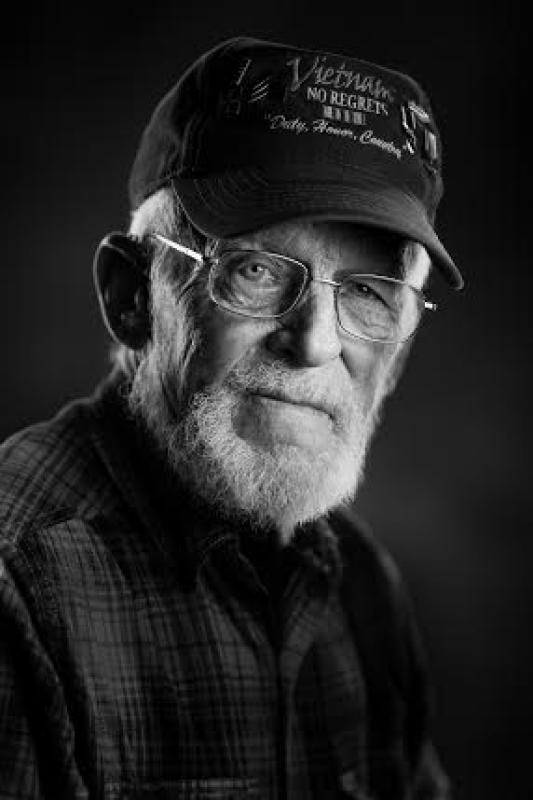

Chesterfield resident John Bisbee doesn’t talk much about his time as a sergeant in Vietnam. Now 68 years old, he said he has PTSD, tinnitus in his left ear, and lung cancer, which he blames on exposure to Agent Orange. He remembers that war as a “nightmare,” but prefers to discuss it only with other Vietnam vets.

Then a few years ago he agreed to be interviewed by local teacher and historian Tom Weiner and by playwright Peter Snoad. Now his memories, and many others, are collected in Weiner’s nonfiction book Called to Serve: Stories of Men and Women Confronted by the Vietnam War Draft, and they will be included onstage in The Draft, which Snoad has based on Weiner’s book.

Weiner has interviewed 62 people about receiving their draft notice, ranging from soldiers to activists to nurses to students. He said the project grew out of “a fascination with how young people coped with one of the most difficult decisions of their lives — a life-and-death choice during their formative years.”

The chronicle is historically relevant, but also offers further chances to heal, he added. “My hope is that people see how hard it was to resist service when they thought it was only hard to serve, and vice versa. There’s still an enormous cultural divide that prevents us from forgiving ourselves and each other.”

Sload described Weiner’s book as “an extraordinary cross-section of experiences,” and he has winnowed down the stories into a play for eight men and two women, performed on a bare stage with mobile panels that show video and image projections in order to set the scenes.

“We want it to be spare, but rich in vision and in language,” he said. “The focus is on these very real people who had to make these life-changing choices — to serve, run and hide, or fight back.”

Many of those interviewed will be attending the show, he said, “and I really hope they see truth in it.” John Bisbee, for one, is excited to see The Draft for himself. He plans to wear his uniform when he and his wife come down to the Academy of Music on Sept. 27.

“I don’t think anyone will ever totally accept a Vietnam veteran,” he said. “It upsets me that it took so long for people to start to understand that us Nam guys aren’t that bad. But I hope the show is a huge success. They’re doing a good thing.”•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.