Some trends are stranger than fiction. When Amazon released the Kindle in 2007 – an immediate bestseller – e-readers looked like the thing of the future. Between 2008 and 2010, digital book sales increased by more than 1,200 percent. In the fourth quarter of 2010, Amazon reported that e-book sales in the United States had begun to eclipse sales of paperbacks.

The challenges of owning an independent bookstore – which, let’s admit it, has never been the most financially secure of careers – looked to be mounting. Between 2000 and 2007, more than a thousand closed their doors nationwide.

Then the tide began to turn. Since 2011, sales of e-readers have steadily declined. Between January and May of this year, e-book revenues dropped by 10%, while print trade books only fell 2.3%, according to the Association of American Publishers.

Meanwhile, the American Bookstores Association is reporting 1,712 member bookstores this year. That’s 302 more stores than five years ago.

Independent bookstores just might be getting their next chapter. But why the turnaround? Perhaps new small stores fill a void left by the closing of big-box bookstores like Borders, which declared bankruptcy in 2011. Maybe we are all pushing back, instinctively, against the pull of the small screen.

Or maybe – my inner idealist hopes – we are starting to remember why we loved bookstores in the first place. That’s certainly how I felt this past week when I walked into World Eye Bookshop in Greenfield, strolled slowly through the stacks, and paged through the same children’s section that I frequented when I was ten years old.

Print book lovers aren’t out of the woods yet. Times are still tight, and business remains unsteady. World Eye had a slow 2014 holiday season, and that’s all it took for the store to announce on May 26 that it was facing cash flow issues and needed to raise $15,000 in sales by June 1 in order to stay open.

World Eye met its goal this spring, but the store can’t ensure it won’t happen again next year. What troubles remain, and how can an independent bookstore hope to secure itself against more tough times? I visited with the owners of several Valley bookstores to try and find out.

THE GIVER

Jessica Mullins sits on the blue couch – a big, comfy fixture at World Eye – with one ear cocked to the phone in her office, visible through an open door. The store is committed to a children’s book drive in Leverett in a few days, and she is waiting on a call back from a book distributor in Pennsylvania to be sure the order will arrive on time.

“Just getting real books into people’s hands, versus the e-readers – it’s especially crucial for kids,” she says. Mullins, 41, is a single mother of two. When she bought the store four years ago, she doubled down on youth programs. World Eye works with the Department of Children and Families to funnel books, bought by customers at a discount, into the foster-care system, and the store runs a similar donation program for school libraries.

Real books for kids, she explains, means less screen time, less eye strain, and a more physical, tactile understanding of how words and pictures combine to make stories.

“Even just the act of standing up and getting a new book,” she says, “gets you moving and interacting with the world, not just sitting in one place for eight hours straight.”

I tell her that I used to do just that as a child, in the very section where we sit. She smiles. It’s rewarding to browse books in person, rather than on Amazon’s top-20 list, and that willingness to be surprised is what we stand to lose when we order through the web. “Last May, we had people standing in line outside, not knowing what they were going to buy,” she says. “They just wanted to come in. They wanted to send the message that they don’t want us out of the community.”

That call to action allowed the store to pay off bills and restock. Mullins says that since May, many return shoppers have mentioned that they “had to remember to come back in” to show their ongoing support.

Still, there’s no guarantee that another bad winter and slow holiday season won’t hurt Greenfield’s Main Street retailers, she says. “We just have to get ready and do our best, and try to make everyone aware that if people don’t shop local, the same thing could happen again.”

The phone rings, and Mullins jumps up to answer it. In her office I hear snatches of her conversation with the distributor: “Pajama Animals doesn’t work for us … Bulldozers are good … Less character-name brands is better … Peanuts is okay … John Deere is always good … Not so much Christmas stuff, please.”

When she comes back, I ask her that simple-hard question: Why does she do it? Why own a bookstore in 2015?

The answer doesn’t shock me. Mullins is a fellow book nerd, and she just couldn’t stay away. Plus, she believes strongly in giving back to the community.

“I knew what I was getting into, with the cash flow crisis,” she says. “I tried other careers after part-time work here. But I always preferred this, and I kept coming back.”

The changing industry has introduced new challenges. Around 2011, she explains, World Eye was getting visits from 20 publishing house sales representatives a year. This year, it’s more like one or two. “Nothing is person-to-person anymore,” she says. “All of the publishers and reps went online, so that’s how we do our ordering now. It’s horrible for small publishers – they get a lot less talk time and shelf time, because distributors aren’t bringing attention to them anymore.”

But for Mullins, the main perk of the job is the flexibility to work along her children’s school elementary school schedule. “To me, that’s almost priceless,” she says. “I’ll figure out my retirement money when my daughter’s in college. In the meantime, as long as I can balance everything, that’s what’s important.”

THE BROKER

Mullins is working to keep a four-decade-old bookstore alive. Over in Hadley, Sam Burton made an even riskier move: in 2009, he added a brick-and-mortar shop to his online bookselling business. The business, now called Grey Matter/Troubadour Amalgamation of Books, is on East Street, just off the bike path.

“The store had its opening party the same year that Pontiac stopped producing cars,” he tells me, perched on a chair among stacks of mid-century novels. “I remember joking with people that my Plan B was to open a Pontiac dealership.”

Burton, 49, spent years watching the print industry decline, and by 2009 he suspected that “enough bookstores had closed that a new, well-run one just might do okay.” Now, he says that one-third of his sales are online. The recession slowed business a bit, he says, “but it wasn’t as scary as I was expecting.”

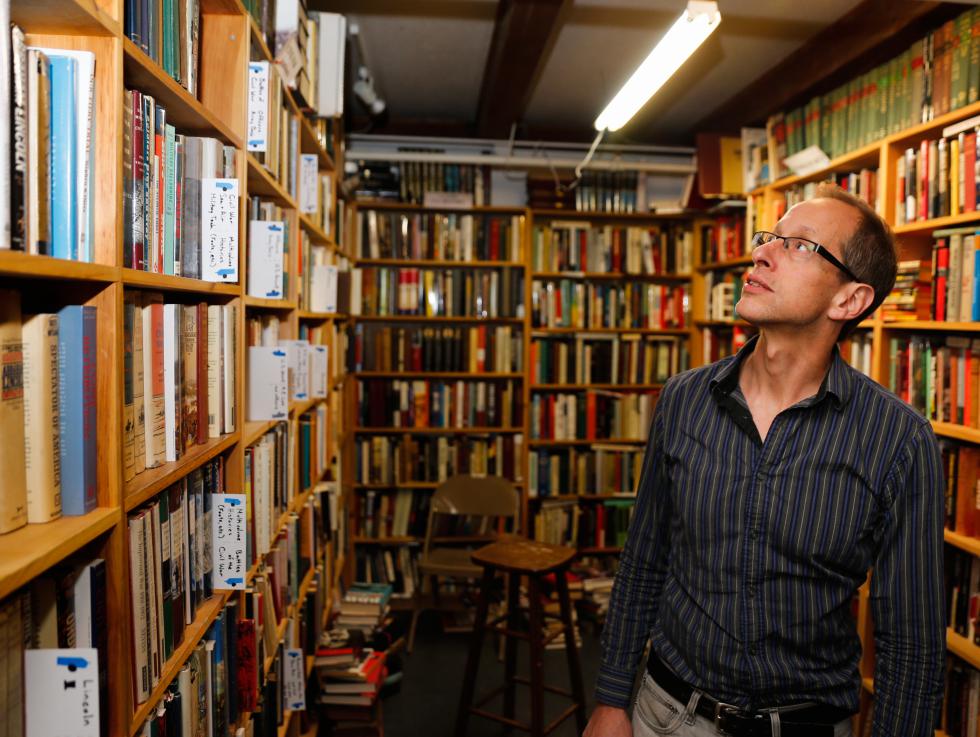

Burton found success by building a reputation for carrying rare, hard-to-find books. He shows me a glass case with first editions of V. and Gravity’s Rainbow, and signed copies from Elie Wiesel, Raymond Carver, and Alice Monroe. One small collection, from the cult 70s poet J. H. Prynne, costs over a thousand dollars.

“Rare books, like academic books, weathered the storm pretty well,” he says, referring to the shaky economy. “The higher-end market hasn’t eroded at all.” The only problem with rare books, he adds, is that it means catering to the rich. “It’s good to get some of that money, but I also want to sell books for three dollars to anyone who wants them.”

That means some months are more flush than others. Burton says Grey Matter does about $200,000 in sales each year, which averages out to an okay living. “But it definitely helps that my wife has a steady paycheck.”

His shop is a labyrinth of shelves, a cellar warehouse lit by fluorescent light and crammed with room after room of floor-to-ceiling reads. Some sections sit naturally up front: Fiction, Law, Literary Criticism.

Go deeper, though, and you end up in “Dante, etc” or “Books of the Weird,” or staring at a long shelf in the Sports section marked “Bullfighting.” Burton has whole sections devoted to Railroads, Marxism, and the Transcendentalists.

Some piles barely count as books: A mound of stapled items in one back room includes minutes from Senate hearings, reports from Game and Fish departments, and a geological survey from 1935 called “Marbles and Limestones of Connecticut.”

“The main threat to my business is myself,” Burton says, adding that he has “maybe 50 or 100” boxes in storage that he’s never even touched. Earlier this month, he bought two collections for more than $4,000 each. When asked why, he throws up his hands. “They were good books!”

Still, every year, Burton has to throw out thousands of books – a dispiriting process, he says. “Most of them are books that I really feel should be important to somebody.”

So it is that Burton comes off as a more kindly Fagin, in search of lost Olivers. He keeps adding more shelves, but he knows that soon, he’ll have to dial it back.

“I keep paying for books like it’s 1999,” he admits. “That’s just not the way other booksellers are operating.”

THE UNVANQUISHED

Burton is referring to the ubiquity of store credit. Grey Matter still pays cash for books, but it’s the only store I know of in the Valley that still does this.

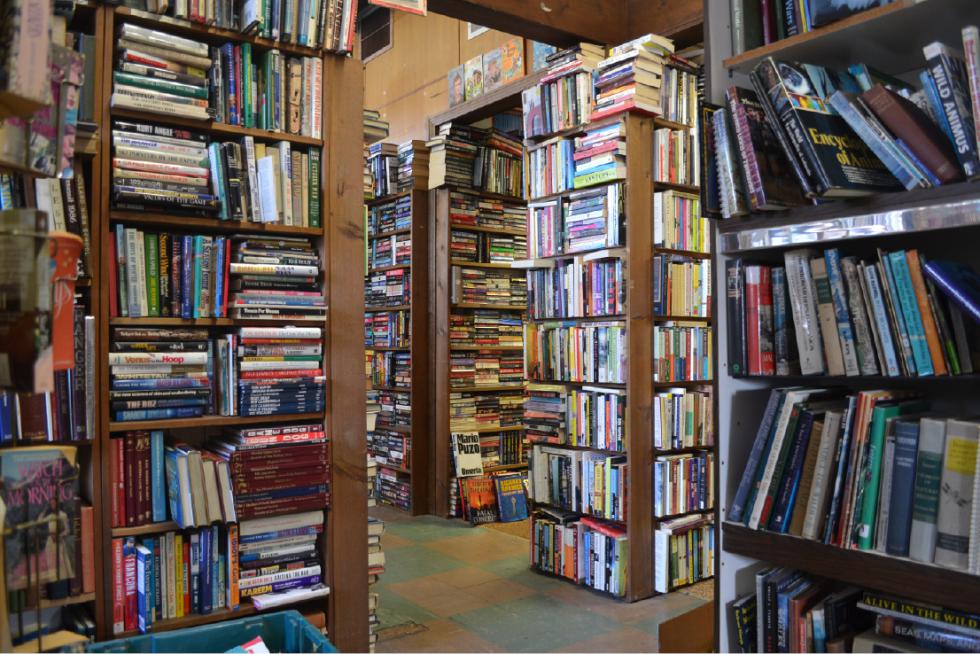

I watch one reader learn this the hard way when he stops in at Redbrick Books, Springfield’s last bookstore. He comes to the counter and waves over Marcia Fuller, 73, the store’s owner. He is carrying three books.

Fuller glances at them for two seconds. “Sorry,” she says. “I don’t accept book club, and these two I’ve got tons of.”

The customer looks nonplussed. He had wanted to swap them for three others in the store. That’s not possible, either, Fuller explains. Even with store credit, every sale must be at least half-cash. Otherwise, she explains, she’s not running a business – just a room full of rotating books.

The customer walks away, grumbling. Fuller raises her eyebrows at me and smiles, unruffled. It’s clear that she’s had this conversation before. She opened Redbrick Books in 1981, and for the city’s last hold-out bookstore owner, she seems pretty serene about the whole business. She’s worked here, on Page Boulevard in East Springfield, for 34 years as the store’s only staff member. She grew up a few minutes away, and she says she’s not going anywhere.

Her secret? No rent. She and her husband own the building, as well as the auto body shop next door, which has been open since 1956.

“I can retire tomorrow,” says her husband Dick, who runs the body shop. “She can, too. We just don’t want to.”

Fuller has been selling a portion of her books online – through sites like Amazon, AbeBooks, Biblio and Alibris – since 2002. I ask her whether those online book sales keep her business afloat. I expect the answer to be yes, but she shakes her head. “I’d be open here anyway. It’s all in service of having a place people can walk in and look around.”

She rises from her office chair to ring up a customer for $7.28. Then she comes back. Most customers, like that one, have been coming for years, she says. Perhaps when the CNR Changchun Railway opens its factory down the street in 2018, she will see some new customers. Otherwise, book lovers tend to hear about Redbrick through word of mouth – or not at all.

“I have loyal customers, but it’s a tough business,” she says. “The recession really hurt, and I saw a lot of stores go out of business. If I didn’t like books so much I’d never be doing this.”

Fuller says she reads three or four books a week. I would think she might have read every book in the store, but in the case of Redbrick, that seems pretty impossible. Here, books are stacked in tall towers, fanned out on tables, balanced on corners, and stuffed thickly into small shelves. The vibe is jungly – less Barnes & Noble and more Flourish & Blotts – and certain sections, like an enormous wall of old mass-market romances, would take most of a lifetime to read through.

For a business owner that absorbs so many lines of text each week, Fuller is a woman of few words. But her passion for books speaks volumes. The store is a part of who she is. It’s no surprise, then, to hear her insist, even in uncertain times, “I’ll keep doing this for as long as I can.”

THE HELP

Nancy and Ken Eisenstein run Boswell’s Books in Shelburne Falls with two employees. One is named Maria Uprichard, and she’s a human who trades labor for wages. The other is Boswell, who just lazes around in the window all day, collecting sunlight.

“She’s the secret to our success,” Nancy says. “It’s like people have never seen a cat before.”

In a small village like Shelburne Falls, it didn’t take long for Boswell – and the Boswells before her – to become a mainstay attraction. Even her owners can’t resist picking her up when she pads through the reading nook in the center of the store, where we are sitting and talking.

Nancy, 68, and Ken, 67, moved to town from Eastern Mass six years ago, and they bought Boswell’s Books about two years later. They had never run a bookstore before. With help from Uprichard, who had worked at the store since 2009, they figured it out.

“Being retired was a big boost to us,” Ken says. “We would never have done this if we weren’t retired. We could never replace our paychecks with this.”

“At this point, we’re doing okay,” Nancy adds. “The first few years were a struggle. But we’re getting to a point now where we’re not just supporting the store – the store is supporting itself. That took a while.”

Boswell’s sells mainly new and used contemporary works, but also stocks birthday presents, holiday gifts, games, and toys. The store carries books by local writers and holds book clubs, readings, and signings. Thanks to a healthy tourist population and good foot traffic – plus the full-time cat – finances are sound.

“You be amazed at the number of people who come in from big cities and say, ‘We have no bookstores left,’” Nancy says. “Even people from L.A. and Chicago.”

If there is to be a bookstore renaissance, I suggest, perhaps small towns are the best hotbeds. If book-loving businesspeople invest locally, maybe the passion will prove contagious.

Uprichard thinks so. Sixty percent of the store’s profits, she says, come from hand-sales – books that are sold by direct recommendation from a staffer. “I think that’s why the big-box stores are going kaput,” she says. “The staff there don’t know their own stock. I go into those stores sometimes and ask them questions about mainstream books. People have no clue.”

Amazon is no better, Nancy says. “Why would you trust online reviews, especially lately?” she says, referring to the news in mid-October that Amazon is suing more than 1,000 unidentified people that the company claims posted fake reviews. “How do you really know where those ratings come from? If I pull All the Light We Cannot See off the shelf, and I tell you that it’s the best book I read last year, you can look me in the eye and believe me.”

Nancy points out that Shelburne Falls, a village of about 1,700 people, has three bookstores (the others are Shelburne Falls Booksellers and Nancy Dole Books and Ephemera). “That tells you something,” she says. “We can all survive. We refer each other to customers all the time. That’s what makes it work.”

That vibrant retail community sounds a lot like the one Jessica Mullins imagines for Greenfield. In her view, the best way to boost World Eye’s odds are for more shops and local businesses to open up along Main Street.

“The more people stop in, the more they understand that we’re about more than books,” she tells me. “I have never seen a local bookstore that doesn’t give back.”

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com