Steve Alves rolls up an chair, sits down at his desk, and opens a spreadsheet of every food co-op in America. He has been compiling this list for years. As his finger flicks the scroll wheel, hundreds of rows spill upward on the monitor: co-ops in states like Idaho, South Carolina, Colorado, Georgia, Wisconsin, California, and Kentucky. The city names are as diverse as America is vast: Long Beach, Durango, Jackson, Athens, Salt Point.

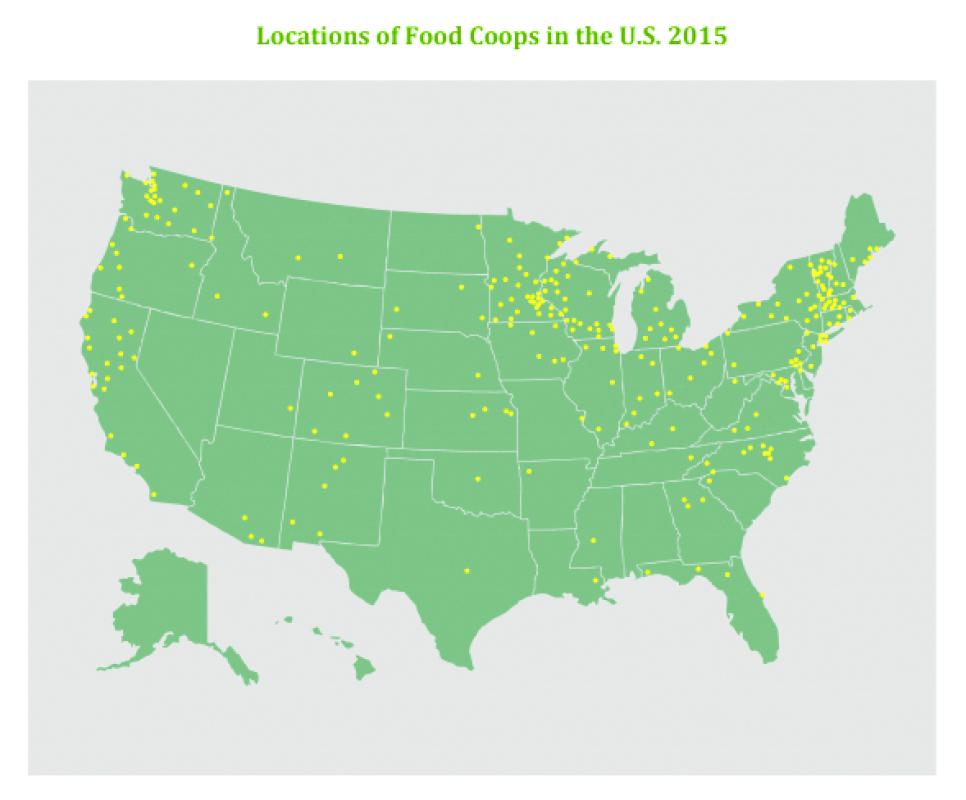

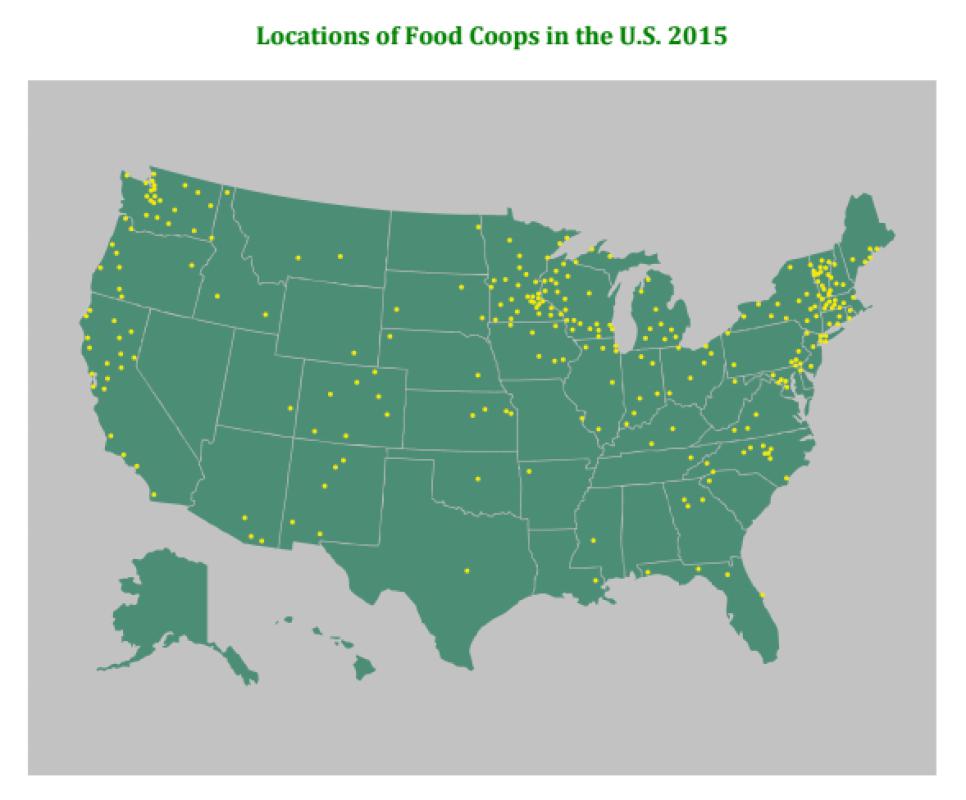

Leaning over his shoulder, I spot a few local cooperatives on the list: River Valley Co-op in Northampton, Green Fields Market in Greenfield, and McCusker’s Market in Shelburne Falls. Near and far, Alves has counted about 320 established food co-ops in the U.S. (that’s not including small startups, which would bring the total to about 400). Out of these, over a third have contributed money to the local documentary Food For Change, which Alves has spent the past seven years bringing to life.

The 82-minute film — which Alves produced, directed, wrote, and edited at his home office in Turners Falls — combines archival footage with new interviews to chronicle the history of food co-ops in America since the Great Depression. But it also offers a snapshot of this moment, when the country is seeing a rise in cooperatively-run businesses (including, but not limited to, grocery stores) that are savvier and more financially robust than the lovable but loosely-run natural food co-ops of the 1960s and ’70s.

The co-op concept is simple: a customer can pay a fee to become a “member-owner,” with the power to vote on decisions relating to sourcing, production, distribution, and the election of a board. The community — not outside shareholders — control how the business is run.

When we hear “co-op,” many of us think “granola.” But as big chains have elbowed their way into the organic and natural foods markets in recent years, local co-ops have had to work harder to define themselves — not only by the groceries on their shelves, but through outreach, classes, charitable work, and community events.

That’s what Alves wants to showcase in this film, which he considers “a powerful new tool” to strengthen the movement. He hopes that co-ops will use Food For Change to educate staff, members, and the public about how co-ops benefit communities.

Alves finished the film in the spring of 2014, at which point he sent it to 121 co-ops, but he continues to edit and improve it. 2016 will be a banner year for the film, he says, with screenings and talks around the country. On Oct. 1, 2016, he will release the film for free online for 18 months — another way to highlight the issues Food For Change addresses in advance of that fall’s presidential election.

If this documentary strikes you as less of a distanced, objective analysis of a movement and more of a morale-boosting attempt to rally America’s shop-local troops, you’d be right. Food For Change is a history-minded, fact-driven work of activism on a topic near and dear to Alves, who is a former Greenfield town councilor. Alves says he was able to go full-time into this project by 2011, but starting out seven years ago, “I didn’t have any money. I just had the idea, and the emotional connection to the story.”

The idea, originally, was a short promotional film for Green Fields Market, part of the Franklin Community Co-op. Suzette Snow-Cobb, the group’s marketing and membership manager, knew Alves as a longtime co-op member and filmmaker.

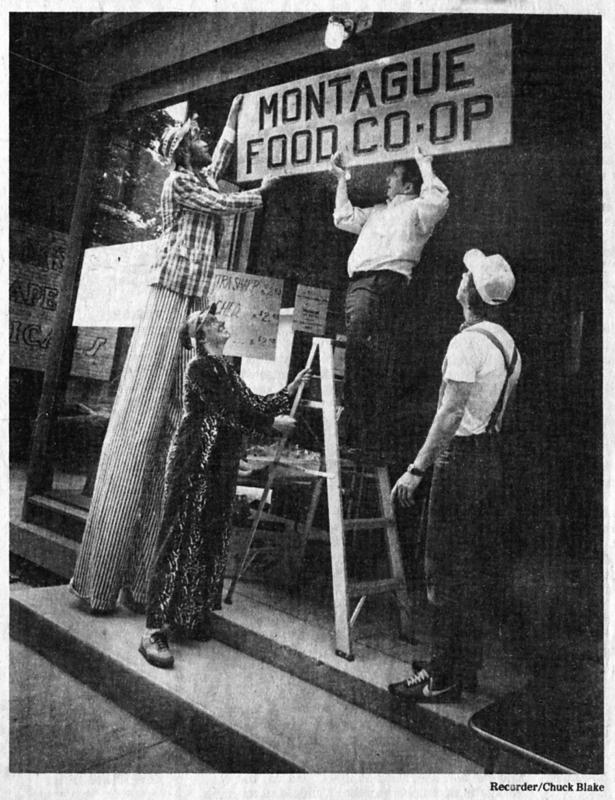

“I wanted him to do a film that looked at the history of our particular co-op, but that also would educate our members and the public about what co-ops are,” she says. “We’re not just a grocery store. Once Steve started researching and interviewing with our older members, who remember us back from when we were the Montague Food Co-op in the ’70s, he came back to me and said: this is a much bigger story.”

Food For Change casts the movement in a national light, but the film still retains a local focus on the Franklin Community Co-op, she added. “It’s great. He’s really taken it to another level.”

Co-ops are embedded in American history, from the Great Depression and World War II up through the economic meltdown of 2008. Even so, co-ops in the U.S. are a small blip in the big picture of the cooperative movement, which is especially strong in Great Britain. The earliest known co-op was founded in Rochdale, England in 1844, and the concept spread throughout Europe. Hitler destroyed them. Mussolini took them over.

“They’d always represented local people power,” says Alves. “This was all stuff that I’d developed strong feelings for in my life, so I felt really in tune with the movement.”

To narrow it down, he decided to focus the film on American co-ops, beginning in the 1930s. The movement in this country has waxed and waned, with three significant periods of popularity: amid the clamor of World War II, then during the social upheavals of the 1960s, and again now, as the natural and organic foods market has become mainstream and more Americans are actively looking for ways to shop local.

Co-ops keep emerging, Snow-Cobb explains, because history keeps repeating itself. They are formed “whenever people have been pushed to the point of being frustrated with what they’re buying — whether it’s the 1830s and you can’t get flour that doesn’t have chalk in it, or nowadays when people are feeling a lack of food access or control over what they need.”

Because of that second-wave co-op movement in the ’60s and ’70s, many of us firmly associate co-ops with small stores selling natural foods. But the goods aren’t what make a co-op. The co-op in Hanover, New Hampshire, for example, sells conventional name-brand products as well as organic and natural foods.

In Spain, the grocery store Eroski has become one of the country’s largest supermarket chains, but it is still run as a co-op. So is the Seattle-based outdoor sporting goods store REI, which in 2014 had 12,000 employees and revenue exceeding $2 billion.

For the (much) smaller co-ops, there are more opportunities to support one another than ever. The Neighboring Food Co-op Association, based in Shelburne Falls, is what Snow-Cobb calls “a co-op of co-ops.” The Valley Cooperative Business Association in Northampton also advocates for collaboration among co-ops that sell entirely different products and services.

Until now, the staff, members, and customers of a community-owned grocery store may not have had occasion to take part in a housing co-op, for example, or an energy co-op. But now’s the time for creative thinking, says Snow-Cobb. “If we can help support co-ops in a variety of areas, then we all have a better chance of hanging on instead of being bought out.”

Food co-ops are also what Beth Neher called “community meeting points.” Neher is the president of the board of directors for the Brattleboro Food Co-op. That co-op has over 6,700 members, which is more than half the population of Brattleboro.

“We serve the community in a huge range of ways, many of them not well-publicized,” says Neher, citing the co-op’s work with the Vermont Foodbank, cooking apprentice programs, classes, and services like yoga and massage, which are formed and led by member-owners. “We’re also a major employer in town, and we contribute in terms of tax dollars,” Neher says. “If we were to leave, you’d see a real shift in how busy the town is.”

Still, misconceptions about co-ops are common. One, says Dorian Gregory, is the idea that a business is managed in the same way as it is owned.

“By which I mean, people often think that co-ops are collectively managed,” says Gregory, president of the board at River Valley Co-op in Northampton. “Some are, but some are not. We run like any retail store, with a general manager, department heads, and staff.” The main difference: the board chooses the general manager to do the hiring, and the board is elected by the members.

“We’re a store with the power to practice democracy,” says Gregory. “My equity investment of $150 gets me one vote. If I put more money into the co-op, I still only get one vote. Compare that to the majority shareholders in a normal corporation. That’s the opposite of democracy.”

Co-ops foster engagement, then, but also community wealth — since the member pool controls assets, money stays within the community rather than draining out through the chain stores.

“It’s very simple: A cooperative is any business that forms to meet the economic needs of the people forming it,” she said. “That’s it. A co-op is about ownership, not about what it’s selling. A co-op can be anything at all.”

I watch those co-ops fly past as Alves scrolls through his spreadsheet. A fair number of them are marked in blue. These are the co-ops that have not directly contributed to the creation or distribution of Food For Change — yet.

Alves — wiry, excitable, and fast-talking — scans the directory. “Look at this thing,” he says, scrolling. “We made this. It’s insane.”

So is his outreach and distribution plan, which is published on the Food For Change website. Well, not insane, just very ambitious: hundreds of screenings, ongoing consultations with educators, the development of a study guide and course curriculum, versions of the film in Spanish and Italian, dozens of theatrical events, trailers, campaigns on Facebook and Instagram, viral clips, radio and television interviews, and framed movie posters in co-ops across the country. It will cost, by his math, $150,000 to do all this outreach, $54,000 of which he has already received in direct contributions and in proceeds from screenings and DVD sales. That leaves $96,000 to raise — ideally, he says, by April.

This isn’t the first time Alves has balanced national and local issues in his filmmaking. After working in Hollywood and in New York City as a film editor for ten years, he moved to Western Mass in the early 80s to work with Ken Burns at Florentine Films. In 1987 he founded his own documentary company, Home Planet Pictures.

One of his favorite projects, 1989’s Life After High School, captured conversations with a wide variety of high school graduates about their blossoming careers and hopes for the future. But the clearest predecessor to Food For Change is probably his 2004 film Talking to the Wall: The Story of an American Bargain, which tracks the successful 1994 campaign to prevent Walmart from building a location in Greenfield. That film hits hard on economic inequality, corruption, monopolies, and corporate supply chains — issues that Alves brings up in Food For Change as well.

“The real benefit of what I’m doing isn’t necessarily the film,” he says. “It’s the fact that somebody made a film about food co-ops — that they’re worthy of that attention. The film isn’t solely about co-ops — it uses co-ops to tell a bigger story.”

Alves wanted to make a film that captured this positive spirit. Some documentaries about political corruption and economic inequality are real downers, he says, “but I’m trying to address those same topics in an inspiring way. You’re seeing stories of people trying to take systemic problems into their own control. That’s a really cool thing.”

And of course, Food For Change is designed as a tool that enables co-ops to run their own conversations — with members and outsiders alike — about the future.

“Co-ops are simultaneously progressive and conservative,” Alves says. “They’ll be ahead on certain issues — local food, constraining GMOs — but sometimes they miss out on opportunities to get themselves heard more. They get huge credit for creating the natural foods market and the organic market, but then Whole Foods and Walmart eat up all the market share. It’s this tendency toward monopoly and empire, and it’s hard to know what to make of it.”

To fight fire with fire, Alves is thinking of Food For Change not merely as a film, but as his contribution to a movement. He has dug through countless collections of archival photos and documents, traveled thousands of miles, and taped hundreds of hours of footage. Now it’s time to throw all of that wood on the fire.

“I’m going to have a ball if I can raise that $96,000,” Alves says. “This isn’t really about the film itself — it’s about the knowledge of the film. Some people will see it, but more people will hear of it. I want to knock them on the head and remind them: our economic system is not etched in stone. It’s malleable.

“That’s what co-ops represent,” he says, turning in his chair to look at me. “You can look at the system from new angles, and be a part of the change.”

Walmart, eat your heart out.•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.