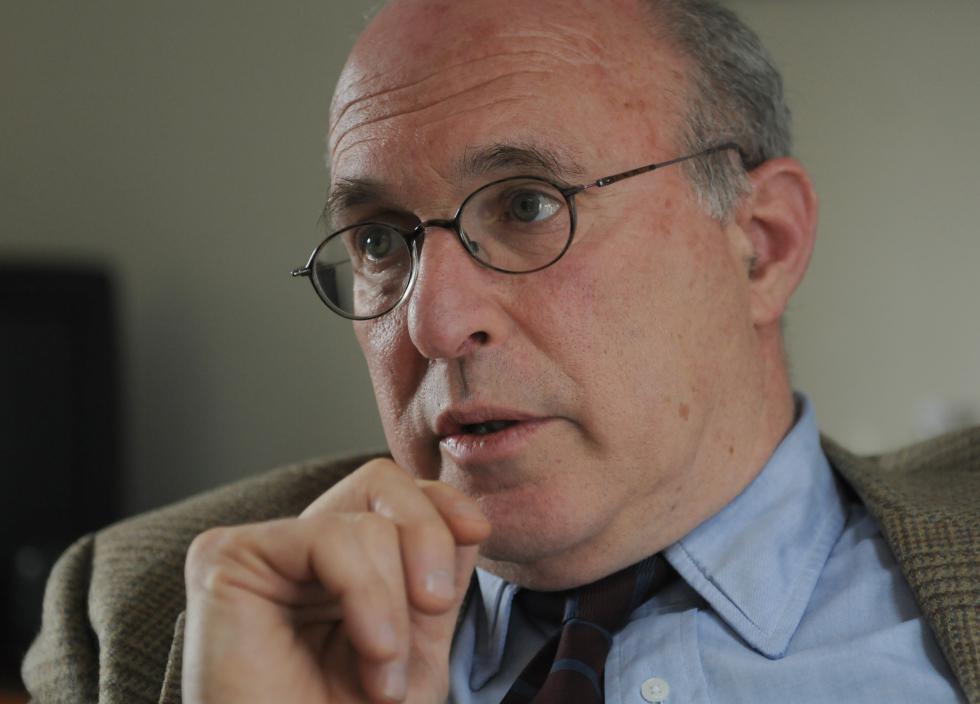

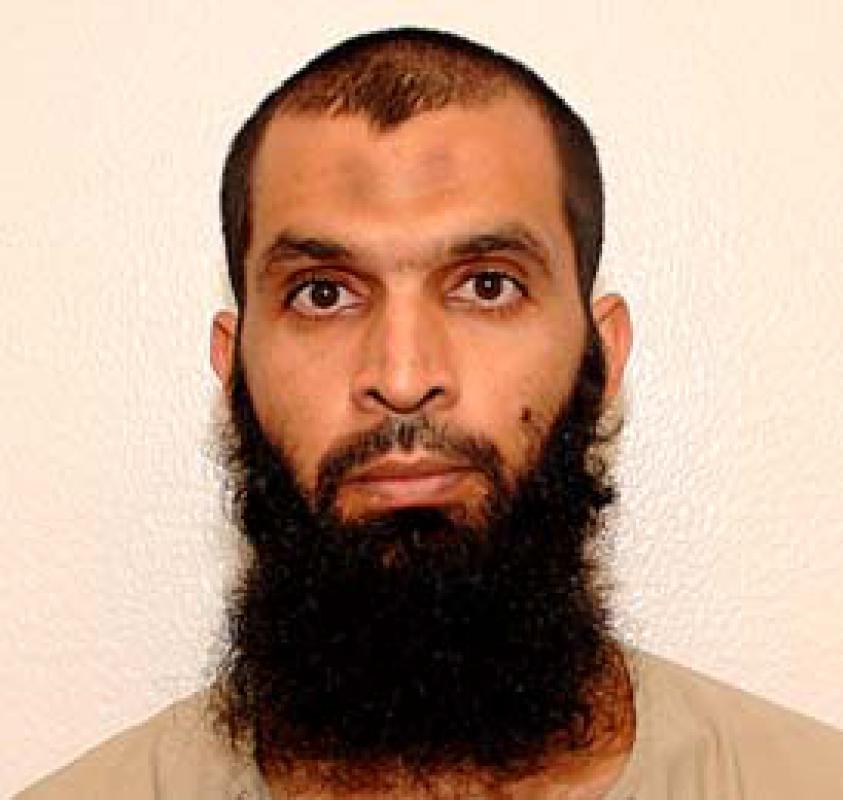

In December 2014, after a dozen years in captivity, Guantanamo Bay detainee Mohammed Abdullah Taha Mattan arrived in Uruguay to begin a new life. The 35-year-old Palestinian was the last to be released out of the group of eight men represented for a decade by Ashfield attorney Stewart “Buz” Eisenberg.

Since then, Guantanamo has remained at the forefront of Eisenberg’s practice. From his office at the Weinberg & Garber law firm in Northampton, Eisenberg says he gets a few emails every hour about the detention center, especially when it’s back in the news.

On Feb. 23, President Obama delivered to Congress a new plan to close Guantanamo. The plan immediately faced resounding objection from Republicans and significant legal obstacles, as has every other attempt Obama has made to close Guantanamo over the past seven years.

This isn’t merely a partisan scuffle. Transferring Guantanamo detainees to U.S. prisons isn’t necessarily a good proposal, and it’s certainly not simple. The Advocate sat down with Eisenberg — who also teaches political science and criminology at Greenfield Community College — to get his perspective on what Obama’s plan means for human rights, due process, and fair conditions of confinement.

Do you think Obama has a better chance of closing Guantanamo Bay now than he did seven years ago?

No, I don’t. But here’s the real question, as far as I’m concerned: is it a good plan? And the answer is a resounding no.

Many of my colleagues believe there is symbolic value in closing Guantanamo. I’m not sensitive to that. Holding these prisoners in the United States — in a supermax in Colorado, as is the proposal — I think it’s a field of dreams: build it and they shall come. So that when we get another suspect, and we want to hold them indefinitely without due process, there’s a bed waiting for them at a supermax where they can be held in isolation — which is torture in and of itself.

That’s the story of our mass incarceration since the ’90s, right? We build these state-of-the-art facilities, streamlining the process of warehousing people, and then we somehow fill them. I think that’s the consequence of the president’s plan, whether intended or not. If we build it, we’ll fill it.

Closing Guantanamo was Obama’s second executive action in office, and it’s faced opposition throughout his presidency. Even Senator John McCain — who has spoken in favor of closing Gitmo in the past — doesn’t like Obama’s newest plan.

I don’t know how it’s going to get through Congress. I think it’s dead on arrival. Bringing these men here means trying them in Article III courts, rather than federal courts where they belong. That violates the National Defense Authorization Act, which is what funds the entire military each year. In 2011, Congress attached what’s called the McCain Amendment to the bill, which says: yeah, we fund the military, unless the president violates the law. So, bringing them here would cause a political firestorm.

The one thing I do agree with McCain about is his adamant and unrelenting opposition to torture. He knows that torture is a foreseeably unreliable way of inducing evidence. For that, I respect him. But he and Sen. Lindsey Graham authored the plan to amend the [National Defense Authorization Act] annually to include a prohibition against transfer except under very limited circumstances, which is complex.

What would you hope to see happen over the next few years?

This is not a perfect justice system. It’s terribly flawed. But I don’t have a better system — this is what we have. So I always resort to the rule of law, which is encoded in the Constitution. The Bill of Rights and due process law is what gives you the opportunity to be heard. You get notice of the charges against you. You get to see the evidence against you. You get to cross-examine the witnesses that are offering evidence against you. You get to be represented by counsel.

If we believe in a government that aspires to freedom, then we can’t deprive someone of their freedom without giving them the opportunity to confront the evidence of a crime and to argue that they did or did not do it. That’s a deep and abiding faith on my part — that our government will continue to revere that system, and foster and promote prosecutions that celebrate and apply that system.

We’ve spearheaded torture conventions on the international front as well. Common Article 3 of the Geneva Convention says that we can capture someone and hold them only until the end of hostilities. If we believe that they have committed war crimes, we try them.

We declared an end to the war in Afghanistan. In Iraq, hostilities have ended. But we continue to hold people indefinitely without charges. There are six Guantanamo detainees on trial right now, but by the military’s own estimate, that trial will take until 2021 because of torture-tainted evidence. And there are 179 or 182 more men who have gone through the gates of Guantanamo who have never been charged.

So, what do I want to see? Charge them or release them. That’s the choice that we have, under both domestic Constitutional due process and under international treaties that the Senate has approved, which are as much a part of our laws as any statute Congress has passed.

You mentioned torture-tainted evidence. Can you elaborate on that?

This is a big topic for me, because Jerry Cohen and I tried the case of Farhi Saeed bin Mohammed. That was a very big legacy case for me in U.S. District Court in 2009 — Farhi Saeed bin Mohammed v. Bush — in which our guy and 40 other people were fingered by Binyan Mohamed.

Mohamed had been taken to Morocco by the CIA and MI5 [British intelligence]. In Morocco, they slashed his chest and penis with a scalpel until he said what they wanted him to say. Later, he disclosed that they threatened to do the same to his parents and brother if he didn’t point out people he’d met at training camps in Kandahar. He testified that the only reason he fingered Farhi was to stop the torture.

Gladys Kessler, the judge who heard the case, concluded that the evidence was inherently unreliable, and therefore insufficient, which meant Farhi has been held unlawfully by two U.S. presidents. I think that case reiterates what international law has long said: Torture-procured evidence is inherently unreliable and unlawful, under both domestic and international law.

Does this really, truly mean that torture doesn’t happen at Guantanamo anymore?

No, it doesn’t mean that torture doesn’t happen.

I’ve had direct representation of eight detainees, and the last one — Taha Mattan — went to Uruguay in December 2014. He had been held in isolation for years and years. With a lot of my clients, I would go down to visit them, and I would be their only non-guard contact with another human being. Human rights groups classify that as torture. Same with force-feeding, and a lot of other practices that still go on.

Many of the men at Guantanamo are held in isolation, but many are not — they have contact with other people and they have recreation time. Under the president’s plan, which is to build a supermax and hold them again in isolation, then once again their attorneys will be looking them in the eye and saying: there’s good news and bad news. The good news is, for symbolic value, we are closing Guantanamo. The bad news is: you won’t get to talk to anyone any longer.

I consider that torture, especially since they haven’t had the opportunity to defend themselves in court and confront the evidence against them.

In other words, this goes beyond waterboarding.

I don’t want to be overly dramatic, but when you’re talking to someone while they’re chained to the floor — someone who has undergone physical abuse at the hands of armed military while in custody — those are horrible interactions. You’re looking into the eyes of someone who is trying to find the way to express the depth of their suffering and fear.

Sometimes it’s sleep deprivation with loud music for 72 hours — they’re kept up, being taken in for interviews or interrogations over and over. Maybe it’s someone from a desert climate who isn’t given a blanket to sleep when it’s 50 degrees. I could go on and on.

Back in 2005, Attorney General Alberto Gonzalez attempted to redefine torture in a memo. He wrote that if it doesn’t cause permanent bodily injury, death, or organ failure, it’s not torture. But the truth is, our country is a signatory to two international torture conventions that define it otherwise.

I don’t know how anyone with a straight face can contend that unless it causes permanent injury or death, it’s not torture. It is what it is, no matter what word you attach to it.

Guantanamo is also torturous because people are kept uninformed about the rest of the world for years. They can’t get mail. Even their attorney’s notes go through review at the security office. They’re not told whether anyone knows about them, or whether their families know that they’re there. Secrecy is the lifeblood of Guantanamo.

Are there ways that you want to see the American media change how it reports on these issues?

Some of your colleagues, like Carol Rosenberg at the Miami Herald, have been stalwart in understanding the wrongfulness of the prison camp, and have reported well on it. But it needs to be part of a broader conversation. Why can’t I get any news right now that doesn’t begin with the word Trump? The fourth estate is our only access to this information, unless you’re a scholar paid to peruse non-popular media sources and make studies of these things. But the media mostly reports what’s spectacular, and it’s really spectacular to say that we’re capturing bad guys.

So many people walk around with the idea that the men held at Guantanamo are all terrorists. It’s not true. Absolutely not true. And it’s been misreported and misreported for 14 years.

Are you still in touch with the men you represented?

A lot of the governments refuse to give us access to them again. Six of the men were transferred to Uruguay. One of them — a hunger striker who had gotten down to 78 pounds — was very unhappy going there. We only get information about him anecdotally, because he felt that continuing to talk to us was like reliving his days at Guantanamo. He got in touch with us to say: I can never thank you enough for what you’ve done, but I really don’t feel like I want to remain in contact with you.

We are a reminder of a very terrible time in his life. He was there for 12 years, much of it in isolation. We respect that.

He wants to go to a Muslim country. He’s Palestinian. But he can never go back, because the Israelis won’t let him into the West Bank. After two years, he can move to a different Muslim country. We’ll see if that happens.

You said that six of the men you represented went to Uruguay. What about the others?

I represented a Syrian national. I represented three Algerian nationals. There have been men of 54 nationalities held at Guantanamo, so my colleagues and I have had to get interpreters sometimes.

The first man I represented was a juvenile, 16 years old when he was captured. We represented him from late 2004 until June of 2006, but he had been there since February of 2002. So he grew up in Guantanamo — his late adolescence was spent there. Now he has returned to Saudi Arabia. He works with his father, who owns an electronics retail store.

What is the population at Guantanamo now?

There are 91 detainees there now, but there have been up to about 700 at any given time. I think a total of 779 have come through.

In 2009, Obama tasked an interagency review team with going through every detainee’s file — which average 1,800 pages each — to say which ones should be cleared. As a result, many have been cleared. Of those 91 detainees that are there, 36 of them remain cleared for transfer. Getting those 36 out of there requires a negotiation with willing recipient countries, like Uruguay — or, most recently, the United Arab Emirates in December. A majority of the men are Yemeni, but we don’t want to transfer them there, because Yemen is so politically explosive right now.

Are you involved in that process?

I’m involved in a support way. I’ve decided not to do direct representation at Guantanamo again, after 12 years and eight clients.

How has it affected you? Is it fair to say that you have enjoyed this work?

There are a lot of jokes about my profession, but the truth is, I’m proud to be an attorney. My line of work, as much as any, commits itself to pro bono work and community service. Many lawyers that you and I know are involved in work that helps open the courthouse doors to those who otherwise couldn’t afford to get in, and to meet unmet legal needs. For me, I’m lucky to be in a position to be able to do what I think is important. I try to promote freedom for people who would otherwise be deprived of it.

I love to work, even when it’s painful. I learn so much by meeting with people who have been victimized by human rights abuses. Guantanamo has taught me that life without hope is not life at all — you have to maintain hope. And sometimes my job is just human contact. It’s not always about writing a brief — it’s about looking someone in the eye and telling them that somebody cares — that somebody knows they’re there.•

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.