Encounters At The End of The World (4 stars)

Directed by Werner Herzog. With Ryan Andrew Evans, Werner Herzog. (G)

Director Werner Herzog wants to make one thing clear: Encounters At The End of The World is not another film about "fluffy penguins." That's not to say they don't make an appearance—the documentary was shot at the South Pole—but Herzog is focused on bigger prey: man.

Shot with the backing of the National Science Foundation, Herzog's film takes him to McMurdo Station, an American research compound in the Antarctic's Ross Sea where his plane—a hulking cargo vessel—coasts to a stop on a runway made of ice. McMurdo is the base of operations for all Antarctic researchers, and a de facto township home to a motley band of scientists, staff, and odd-duck academics who found themselves drawn to the region's austere and isolated beauty.

It's that same beauty, seen in a friend's footage of divers working in the impossible blue of the water underneath the ice, that originally draw Herzog to the region, and when the film begins, it seems for a bit that Encounters will be a nature film in the PBS mold. But when he arrives, Herzog is dismayed by his first glimpses of McMurdo; a dirty place crowded with noisy machinery, it looks to him like "an ugly mining town."

Suddenly, we're back where we belong, where the acerbic Herzog's very particular vision leads the way. To a great extent, the success or failure of his work depends on how the viewer feels about the man himself. His narration is that of a willfully dyspeptic artist, and he finds much to disdain in what mankind has done at McMurdo. He can't understand the need for a soft-serve machine and an ATM in the Antarctic, and the aerobics and yoga classes on offer are "abominations." Worse, he arrives in the midst of the South Pole's summer of 24-hour daylight. "I loathe the sun," groans Herzog, who's relieved when a whipping storm buffets the compound.

Yet beneath his crusty facade one gets the sense that Herzog is above all a curious man, one ultimately less interested in the landscape than its inhabitants. What draws them to such a desolate place? How does a banker from Colorado become a bus driver at McMurdo, or a philosopher a forklift operator? What brought plumber David Pacheco, who claims he's descended from Aztec royalty, to this remote kingdom? As his interviews progress, you can feel Herzog warming to this strange collection of people, and even when he's at his most blunt—he cuts one woman short in a voiceover that explains "her story goes on forever"—there's an undercurrent of tenderness for society's misfits, probably because the director himself so easily fits the description.

When he is finally allowed into the field (everyone at the base undergoes a two-day training regimen, which leads to one of the film's funniest scenes) Herzog captures some of the physical wonder of the region. Vulcanologists rappel into active volcanoes, and the divers delve back into the water under the ice, their lanterns illuminating creatures straight out of science-fiction. The divers have a name for these descents that captures the otherworldly wonder of the place—"going down into the cathedral"—and Herzog's use of seal calls and choral music makes the connection more concrete: this is sacred ground.

There's a touch of sacrament, too, in the shrines that McMurdo's residents have carved into the tunnels of ice running under the base. Many have left mementoes of their time there, tucked into niches in the frozen walls. Herzog wonders what some future explorer make of it all as he looks ahead to the day humanity becomes extinct.

But in a film so concerned with the human animal, it's in the end a penguin—a dot of black lost in a world of white, on a journey of his own—who provides the film's best, if saddest, moment, one that remains with you long after the lights go up.

The Wackness (3 stars)

Written and directed by Jonathan Levine. With Josh Peck, Ben Kingsley, Olivia Thirlby, and Famke Janssen. (R)

The Wackness, which seems poised to be a breakout hit for young writer/director Jonathan Levine, is the kind of indie movie that polarizes crowds. Over the top but earnest, hip yet vaguely ludicrous, it seems destined to be fondly remembered by many and quickly forgotten (if seen at all) by anyone over 40.

Set in the summer of 1994—the year Levine graduated from high school—it's a coming of age story for a generation reared to the beats of Wu-Tang Clan and A Tribe Called Quest. (Rapper turned actor Method Man even has a small role as a drug dealer in the film, cementing Levine's bona fides.) Levine deserves credit for setting his film in a period he experienced firsthand; though at 30 he's not exactly over the hill, the decade or so between high school and the first throes of true adulthood is a yawning chasm that has swallowed many less cautious filmmakers who tried to appropriate another generation's history.

His stand-in here is Luke Shapiro (Josh Peck), a New York teenager whose disaffection is a carefully cultivated way to deal with both the strife at home and the pressing concerns of growing up. His family is on the verge of being evicted from their Upper East Side home, and his father—like Jim Backus as James Dean's father in Rebel Without a Cause—is an ineffectual milquetoast unable to understand his son or hold the family together.

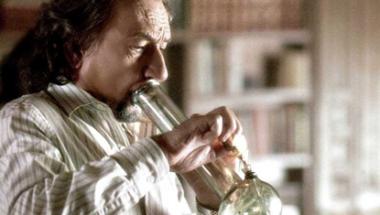

To help sort things through, he has regular sessions with unorthodox psychiatrist Jeff Squires (Ben Kingsley), a doctor with issues of his own, most notably a big drug habit that the pot-dealing Luke is happy to support. As their relationship grows, it's not quite clear who's helping whom—Squires is a man-child who drops water balloons from his balcony and dispenses advice like "you just need to get laid," while Luke is a child-man yearning for the knowledge of his elders, but too caught up in play-acting to realize it. Both are stuck posing, as much for themselves as others.

The catalyst for change in both their lives is Squires' stepdaughter Stephanie (Juno's Olivia Thirlby), a worldly classmate of Luke's who initiates him in the painful world of relationships wrought of teenaged fickleness. With her circle of friends away for the summer, she reels Luke into a brief relationship that awakens in him a tenderness he seems not to have known he possessed; just as quickly, and just as thoughtlessly, she moves on.

It's unfortunate that the relationship of Luke and Squires becomes the main thread in the film; what begins as a stretch becomes ridiculous before long, when doctor and patient become graffiti artists, drinking partners and cellmates. By the time they're traversing Manhattan selling pot from one of the city's mobile ice carts, you're long past disbelief. Kingsley does what he can with it—he's the best thing in the film—but the writing, which includes the line, "I'm mad depressed, yo!" is far better suited to the mouths of the younger characters. There, however stilted, it can make us remember what it was like to be young, in love, and confused.

Step Brothers (2 stars)

Directed by Adam McKay. Written by Adam McKay, Will Ferrell. With Will Ferrell, John C. Reilly, Mary Steenburgen, Richard Jenkins, and Adam Scott. (R)

Will Ferrell: we get it. We do. But the clock has long since struck, and it's time to return to the land of grown-ups. There's no shame in a collared shirt, nothing wrong with a steady job, and in the end, it's okay not to be the craziest kid on the block. Remember John Belushi, and please, if you're going down, don't drag John C. Reilly with you.

Other than that, what can I say? Step Brothers is another Will Ferrell movie; if you like him, you'll love it in all its screaming intensity; if you find most of his latest films to be foul-mouthed cut-and-paste jobs of his earlier work, you'll likely be disappointed.

Written with long-time collaborator Adam McKay (Anchorman, Talladega Nights), this episode in the series features Ferrell and Reilly as Brennan Huff and Dale Doback, two middle-aged men who never left the family nest. Eternal adolescents, they spend their days making microwave nachos, practicing the drums, and masturbating to yoga workouts on cable TV. When their far more normal parents unite in marriage, the pair is thrown together.

Bitter enemies at first, they quickly discover their shared interests—dinosaurs, karate and the homoerotic appeal of John Stamos—and become fast friends. They also find a common foe in Brennan's obnoxious brother Derek (Adam Scott, great), a slick Tom Cruise look-alike who talks in the clipped diction of a Variety blurb. Scott, just by being a bit more real, overshadows the stars, and some of his lines are destined to be quoted in college dorms for years to come.

For a time, all's well in a hyperactive way, but the hijinks of "the boys" soon drive their parents to divorce, and with the sale of the family home they're out on their own, forced into the scary world of adulthood: jobs, apartments and wardrobes that aren't anchored by Star Wars tee shirts.

So, for a time, Ferrell and Reilly grow up. But Ferrell has always been about the absurd inspiration born of over-confidence, and he can't resist an ending that, though not quite fairy-tale quality, at least lets his characters keep their endless childhood churning. It's a wrap-up we've come to expect from him, an actor whose gross-out juvenilia is inevitably balanced by the warm embrace of family.

Also this week: Midnight screenings have long been the place to check out films that might fall outside of the mainstream, and the tradition lives on at Northampton's Pleasant Street Theater. This week the cinema plays host to Multiples of Three, billed as a screening of experimental films and featuring local filmmakers Ben Balcom, Alex Ward, and Josh Weissbach. The show begins at midnight on Thursday, Aug. 7, and features a reduced ticket price of three dollars. Who says art has to be expensive?

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.