In the Subscriber Enrichment Packet for the Berkshire Theatre Group’s world-premiere production of The Stone Witch, playing in Stockbridge through August 20, director Steve Zuckerman says of the playwright, Shem Bitterman, “He writes instinctively, and it just pours out of him. [Then] he brings this raw material, and I help shape it.”

I found that statement half useful and half baffling. To this first-nighter’s ear, the script certainly seems to have poured, even gushed, from Bitterman’s pen, but it hasn’t yet been shaped into a coherent play.

It starts with a well-worn setup: Simon Grindberg, a revered and aging children’s book author/illustrator, hasn’t turned out anything in 12 years. His editor convinces Peter Chandler, a young and ambitious toiler in the same field, whose artistic style is remarkably similar to Simon’s, to visit the old guy in his forested hideaway and try to help him finish the book – others have already tried and failed – or, as the editor broadly hints, even write it for him. But, she ominously warns, “Simon is a bit … unusual.”

It starts with a well-worn setup: Simon Grindberg, a revered and aging children’s book author/illustrator, hasn’t turned out anything in 12 years. His editor convinces Peter Chandler, a young and ambitious toiler in the same field, whose artistic style is remarkably similar to Simon’s, to visit the old guy in his forested hideaway and try to help him finish the book – others have already tried and failed – or, as the editor broadly hints, even write it for him. But, she ominously warns, “Simon is a bit … unusual.”

This premise could generate several distinct plotlines. Horror: Young man shows up at the isolated house and discovers the old guy has gone mad and homicidal. Salvation feel-good: Loneliness and writer’s block have turned the old man nasty and antisocial, but the youngster restores his humanity and work-rate. Thriller à la Deathtrap: Older tapped-out author plots to steal younger man’s original work. Or even, considering the chosen genre, fairy tale: Brave prince journeys to a forbidding castle inhabited by a man-eating ogre, not to slay but to tame it.

The odd thing is that The Stone Witch contains elements of all these options, but can’t seem to decide what to do with any of them. It’s a relationship play that gets spooky; a suspense piece with a sentimental core; a fable without a moral.

Simon is, indeed, an ogre: irascible, acerbic, derisive, self-centered, short-tempered, willful and semi-alcoholic, but also insecure, self-pitying and quite possibly demented – not at all the personality you’d associate with a beloved creator of children’s classics (which is interesting in itself though nobody mentions it).

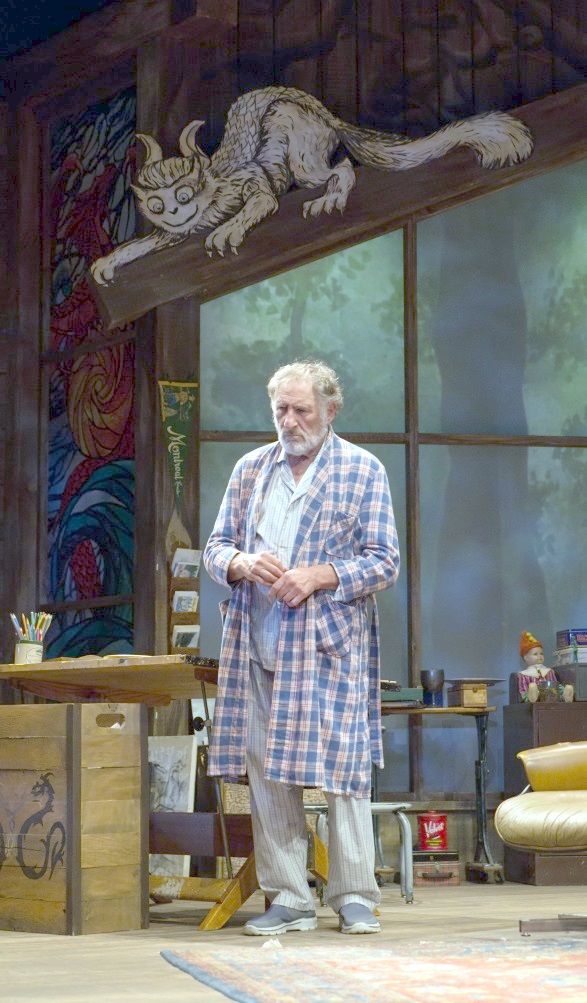

Judd Hirsch plays Simon. He’s a genuine Emmy- and Tony-winning star attraction, and he repays the price of admission. He grabs his unwieldy role with both hands and shakes it into life, pacing furiously, nervously, anxiously, flinging out bombastic pronouncements to intimidate the young interloper and his own self-doubt. It put me in mind of Mark Rothko in the play Red – an artist consumed by ego and dread whose default pose is bullying.

The character of Simon seems to be based – rather libelously – on Maurice Sendak. The blown-up illustrations from his books, pinned to the beams of his woodside studio, bear a can’t-be-coincidental resemblance to some of the creatures in Where the Wild Things Are. Simon brags that he was the first to draw a naked child in a picture book – as in Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen. And, like Sendak, his publisher is Harper & Row. Except that Sendak was not a reclusive paranoid, and worked steadily and productively right up to his death in 2012.

The character of Simon seems to be based – rather libelously – on Maurice Sendak. The blown-up illustrations from his books, pinned to the beams of his woodside studio, bear a can’t-be-coincidental resemblance to some of the creatures in Where the Wild Things Are. Simon brags that he was the first to draw a naked child in a picture book – as in Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen. And, like Sendak, his publisher is Harper & Row. Except that Sendak was not a reclusive paranoid, and worked steadily and productively right up to his death in 2012.

The Stone Witch is the title of the manuscript Peter brings to the great man’s rural retreat. It’s his baby; he’s been working on it for years. But Simon tosses it in the trash, sight unseen, then announces he likes the title and will use it himself.

Rupak Ginn is an attractive and likeable young actor, though he’s challenged toward the end when Peter’s trajectory lurches suddenly back into its original track and then onto still another. The character, and I guess the actor, is of Indian descent, and a point is made that his surname is Anglicized – perhaps a hint that he’s a bit of a chameleon, but it amounts to another tantalizing dead end. The editor, Clair Forlorni, whom Simon describes as “a barracuda in Armani,” is convincingly portrayed by Kristin Griffith – sleek, brainy and coolly manipulative.

Yael Pardess designed both the set, a wood-beamed studio looking into deep woods, and the striking animated projections that seem to rise out of them. These include the title character and, at the end, an example of Peter’s own illustration style, which (another puzzling plot anomaly) doesn’t seem at all similar to Simon’s after all.

The director insists the play is centrally about “creativity [and] the price one pays for being an artist.” But it’s not really, unless we want to accept that Simon is an asshole because he’s an artist, or that there is any significant cost involved in producing the play’s final, rather gratuitous creative expression.

BTG’s Enrichment Packet also contains an interview with the playwright. He explains that the piece as performed is the product of a draft “80% done” that’s honed with the director and then further in rehearsal by the actors. There, he says, Judd Hirsch “intuitively” provided the ending.

To me, that says everything about the script’s core problem. It plays exactly as if the author doesn’t know where it’s headed, going off in several directions and trying various themes on for size. The result is a play full of intriguing possibilities that, like a fairy-tale prince lost in a dark wood, can’t decide which path to take.

Photos by Emma Rothenberg-Ware

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com