Alien. Blade Runner. Black Hawk Down. The Martian. Over the decades, director Ridley Scott has built a career on making the kinds of films (often with a bit of a sci-fi bent) that combine quiet moments with explosive action. But for me, he will always be first associated with a film that many people are surprsed to find he directed at all.

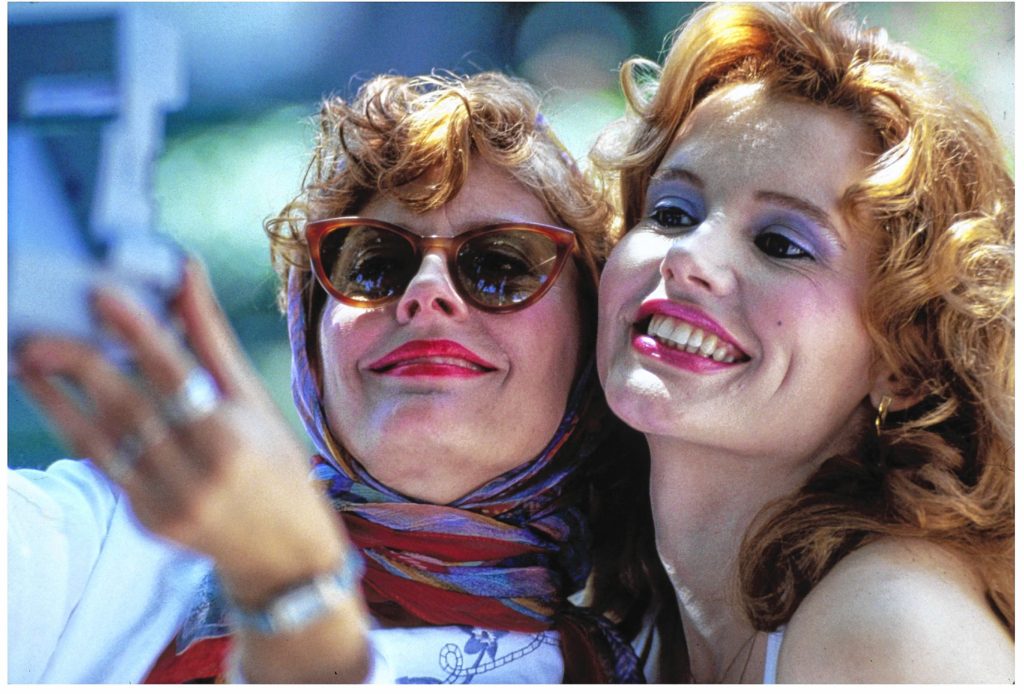

That film is the now-classic 1991 road movie Thelma & Louise, screening this week at Cinemark Theater in Hadley and the Rave/West Springfield 15 as part of the film’s 25th anniversary celebration. Written by Callie Khouri (currently riding high as the creator of the TV series Nashville), the film — which has retained a spot in my memory due to the fact that my mom was wise enough to take teenaged me to see it in our local theater — stars Geena Davis as Thelma and Susan Sarandon as Louise, two friends who decide to light out on a short road trip as an antidote to the dull drip of their daily lives.

What begins as a (relatively) carefree jaunt quickly turns dark when Thelma is assaulted in a parking lot, and Louise, after saving her friend, turns to punish the attacker. From the moment the smoke clears, Louise is a fugitive, on the run both from the police and her own past. Thelma decides to stand by her friend, wherever the road might lead. Along the way, they cross paths with a handsome thief (a young Brad Pitt, whose career was launched in his scenes here), and a dogged cop (Harvey Keitel).

But the relationship between the two leads is the heart of the story, and so strong is their bond that the ending — which I won’t reveal here, despite it being referenced any number of times in other media over the years — is entirely believable, and even joyous, despite being as perfect a big-budget freeze-frame as one could imagine. In the end, it turns out to have an awful lot of Scott’s style, even if the subjects are mostly Earth-bound.

It’s hard to believe it has been 25 years since my mom and I went off to that matinee. I hope that this new screening inspires some of today’s moms of young men to take them to the theater over the weekend. Khouri never claims that her characters have all the right answers, but for the younger me, it was a revelation to get to see two women leading a film and asking their own questions.

Also this week: in Shelburne Falls, Pothole Pictures screens Man With A Movie Camera on Friday and Saturday nights at 7:30 p.m. (live music on stage at 7 p.m.). A silent film from 1929 — presented here with a live score performed by Wayne Smith and Lysha Smith, on cello and electronica — it was shot over a four year period in Moscow, Kiev, and Odessa, directed by Dziga Vertov and filled with everyday life in the early days of the Soviet Union: machinery, trains, workers, and so on.

For Vertov, it was an experiment in purity, a documentary style so strict that, if it had caught on, would have undercut his own job security by making more “artistic” film interpretations seem dangerously subjective. For modern viewers, it is a time capsule from a mostly unseen land, and a chance to experience the past and the current together, since the film and score come together to produce a sum greater than their parts. In the end, one has to wonder just how different America and the Soviet Union truly were on the human level. There is one shot of cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman clinging to the front of a train while he looks for the best angle to get his shot. As I stared at the image, wondering why it looked so familiar, it hit me: Kaufman looks an awful lot like Buster Keaton during an outtake of The General. That film was released in 1926, three years before Man With A Movie Camera, but one wonders if the Soviets kept a secret stash of slapstick around, to help liven things up in the time between shots.

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.