Ruth Sanderson’s Magic Eye

Easthampton author Ruth Sanderson says she has nearly lost track of the number of children’s picture books she has published over the past three decades (she counts 85, at least). But every one of those books conjures a fully-realized world, where humans, animals, mythic creatures, and fantastical landscapes come alive within the span of a few dozen pages.

Quick, cartoonish illustration seems to be the name of the children’s publishing game these days. But Sanderson makes each new story into a work of art, meticulously rendering each scene in pencils and paints before digitizing the paintings in a big flatbed scanner. She can’t help it — she sweats the small stuff.

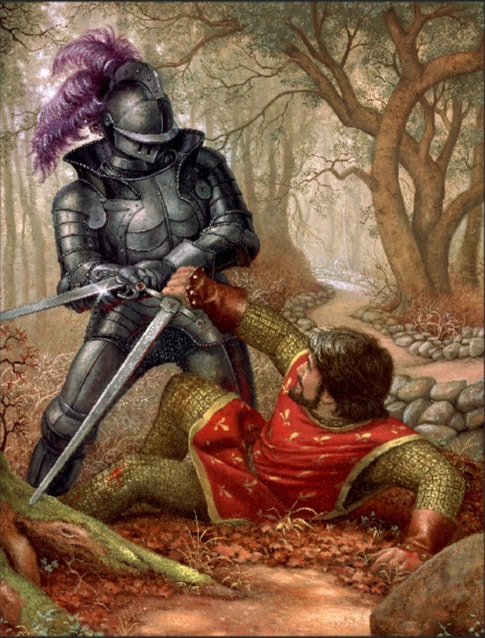

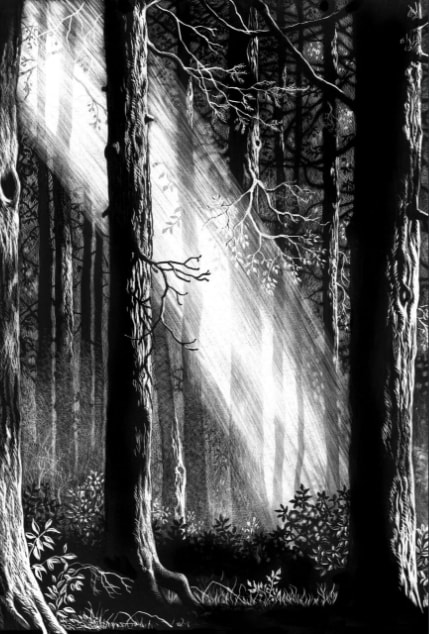

A mere glance through her fairy tales reveals the value of such focus. In her forests, silky moisture glints on dewy blades of grass. On her mountaintops, bits of flecked stone spray from beneath a horse’s hard-scrabbling hooves. Her characters, too, are intimately formed. Threads sprout from the frayed shirt of a beleaguered huntsman. Firelight glows on a young maiden’s warm forearms. Purple shadows fall on a tired boy’s eyelids.

These days, the fine art of making pictures for kids has mostly been swallowed up in a Cartoon Network wave of pop-colored surrealism. But Sanderson’s scenes are still doggedly naturalistic, even as they brim with magic. Forget old-fashioned — these books are downright Pre-Raphaelite.

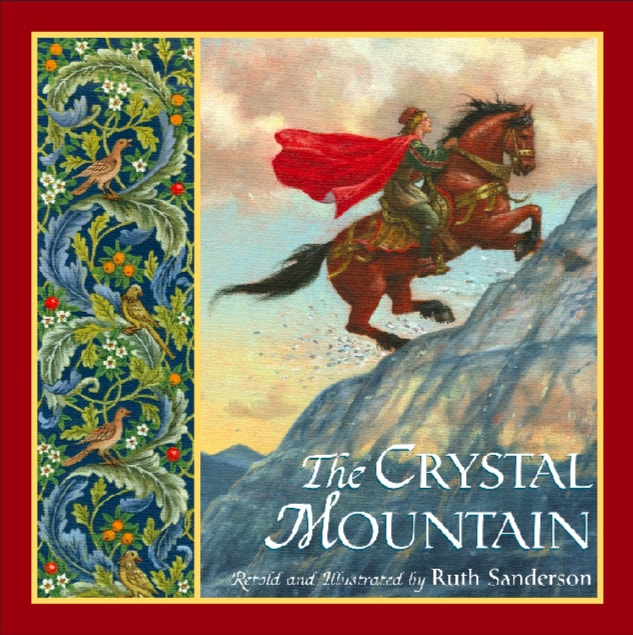

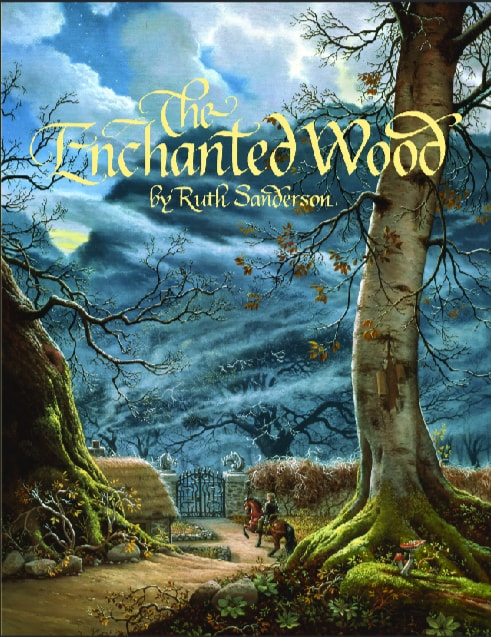

It’s what tempted the Northampton- based Interlink Publishing Group to recently begin publishing new editions of Sanderson favorites like The Enchanted Wood and The Crystal Mountain (which, like most of her fairy tales, were originally published by Little, Brown and Company).

“Ruth Sanderson is a national treasure,” says Interlink publisher and editor Michel Moushabeck, who used to read Sanderson books to his own children when they were young. “When I heard that some of these beautiful classics have been declared out-of-print by her original publishers, I jumped at the opportunity to bring them back into print.”

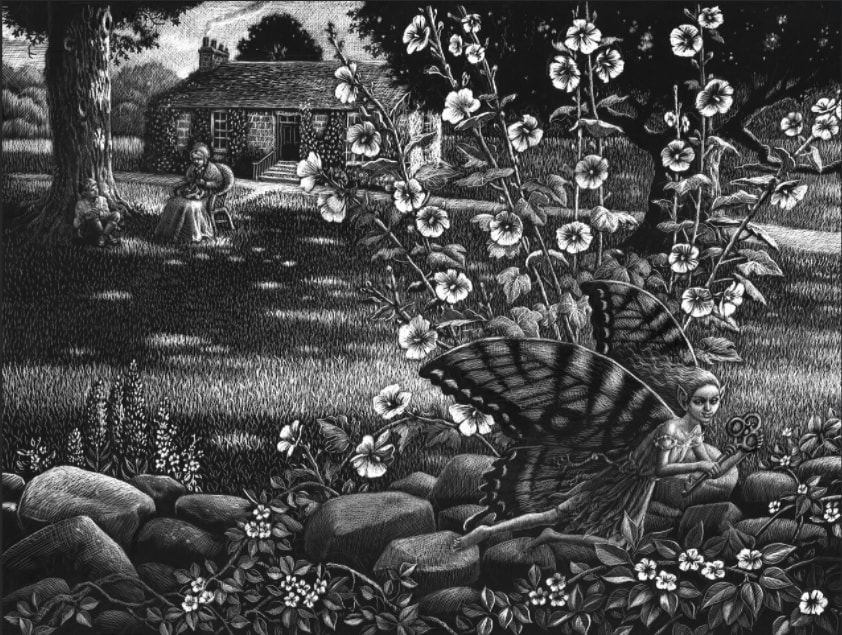

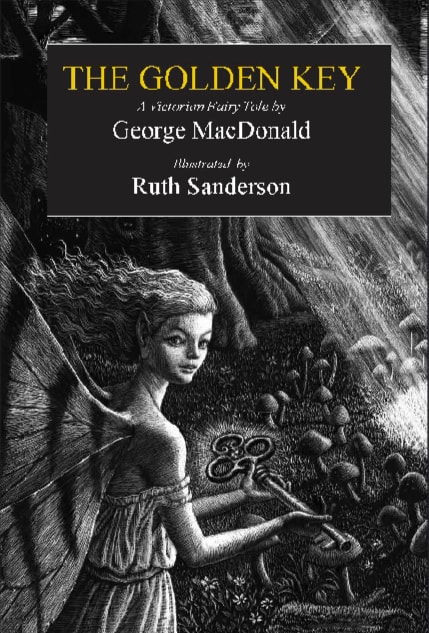

And while some of those old favorites are once again coming into bookstores, Sanderson’s newest endeavor — a short novel called The Golden Key — is breaking new ground. Written by George MacDonald, this Victorian fairy tale is beautifully illustrated by Sanderson — who has long been inspired by Renaissance art, icons, illuminated manuscripts, old engravings, and woodcuts — in a style relatively new to her: scratchboard.

Sanderson doesn’t worry that she will run out of ideas. Instead, she says, “I worry that I won’t have enough time to finish all of the ideas that I have.” A native of Monson, Sanderson has lived in Easthampton for the past 10 years. Curious about what keeps her going so tirelessly, we spoke with her recently at her home studio on Clark Street. The following interview has been edited and condensed.

Hunter Styles: It’s an unusual opportunity to see older books come back into circulation with a different publisher, like Interlink is doing with some of your fairy tales. How did that opportunity come about?

Ruth Sanderson: Four or five years ago, I was introduced to Interlink by Jane Yolen, who had done a fairy tale cookbook with them. She said they might be interested, so I went and met with them. It’s a dream. In this day and age, unless you hit the New York Times bestseller list — or you’ve done a book with a celebrity, or you win some really big award — your book will just go out of print. But a smaller independent publisher can basically do what it wants.

I’ve been doing fairy tales since about 1990, when I wrote The Twelve Dancing Princesses. Interlink picked it up. I also suggested one called Rose Red and Snow White, because I was really unhappy with how dark the first edition of that book printed. Now I get to redeem it! Interlink has also asked me to do an original fairy tale. I’m very excited about that. So far The Enchanted Wood is my only truly original fairy tale. Otherwise I’ve mostly done retellings, although I go off quite a bit from the original stories and make them my own. The Snow Princess, for example, had never been made into a children’s book — it was a Russian opera. So writing that one felt pretty original.

Hunter: The number of books you’ve been able to put out seems staggering to me.

Ruth: It is a bit staggering. I know people who have illustrated 200 books, and I really can’t imagine how they’ve done it. Well, I guess their style is faster. I have a rather slow style.

These fancy 32-page full-color books with elaborate oil paintings — I haven’t done 85 books like that! I couldn’t have. Those books take me a year each, or a year and a half. Chapter books, with black and white interiors, are faster. And for 15 years of my early work, I didn’t use any oils — I worked in watercolor and acrylic.

It was only when I got a commission to do an illustrated version of Heidi that I switched to oils. That one just felt like it needed a really traditional painting style. I had a long deadline for it, so it all had time to dry. I could be working on two or three scenes at once. After that, I had to keep going in oils. I’d been using oils since I was 13, and I just loved it.

But the book industry is changing, and producing more, and keeping books in print for less time. I couldn’t afford to work in oils today, and I haven’t for about 10 years now. Or rather: they can’t afford to pay me enough, for the number of books that sell. It’s just economics. It is what it is. But I could afford to do it back then.

Hunter: How has your illustrating style evolved more recently? And has that been a welcome change?

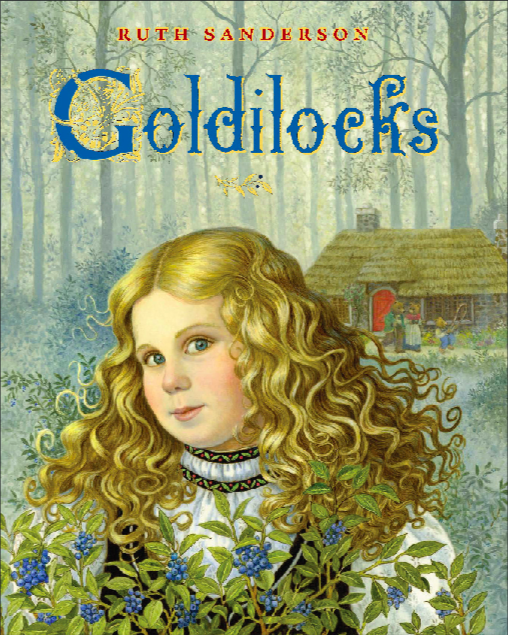

Ruth: For the most recent Little Brown book I did — Goldilocks — I changed my style. I did under-drawings for the entire book in pencil and graphite, then scanned them into my computer and printed them out in a sepia color on paper. Then I tinted them in oils on top. So, it’s a bit of a lighter style. Because that’s sort of a younger fairy tale, it matched the younger age group. And it took me half the time.

Hunter: Did you go to art school?

Ruth: I went to the Paier School of Art in Connecticut. It’s accredited now, as the Paier College of Art. It was a very traditional fine art school, based largely in portraiture. That was good for me, since I’ve always gravitated toward traditional art. Fully rendered pictures always appealed to me more than modern art and simpler styles.

Hunter: Did other students there go into illustrating for children?

Ruth: Yes. Some people ended up in advertising. Some do book covers now. Some do children’s books. Some went on to completely different things.

Hunter: Becoming an author requires writing skills too, of course, and it seems a lot of art programs don’t teach writing as well.

Ruth: Paier does not — they had no writing. There’s only one program in the country that teaches both. It’s at Hollins University in Roanoke, Virginia — an intensive six-week summer program for an MFA in writing and illustrating for children. I’m the co-director of that program, and I designed it. Since the early 1990s, it’s been very successful.

Hunter: How did you find your way into your own writing style?

Ruth: At first, I came into writing with a lot less confidence. So I starting out by retelling fairy tales. That really boosted my confidence. I didn’t retell from just one source — I found different sources of the story, picked my favorite parts, and molded them into something new that was mine. And this gave me the courage to begin writing original stories, like The Enchanted Wood.

I feel that even as a reteller, I’m adding a lot to the tale. Right now I’m working on a retelling of Snow White and the Seven Dwarves for a young adult audience. It’s called The Seventh Dwarf, and it’s premised on the idea that it was a dwarf who made the magic mirror for the queen. That one uses a different character’s point of view.

You note the theme here — fairy tales! I can’t get away from them!

Hunter: I see a lot of Western and European folklore in your books, but your interests seem to include stories beyond those places, even when your art takes a European style. The Crystal Mountain, for example, has both Chinese and Norwegian influences.

Ruth: I would love to do more multicultural fairy tales. It can be tricky, though, to take up traditional stories from cultures that aren’t yours. Like, if I do a retelling of a Native American story, then just go off and invented a bunch of non-traditional stuff, would that be acceptable? I’d feel awkward about it. It’s not my culture — I’m Polish. Those relationships are important. So I have mixed feelings about whether it would be appropriate for me to do a story that’s strictly African, for example.

It’s something I’ve steered away from a bit, but I don’t think of myself as boxed in. A friend of mine recently commissioned a scratchboard illustration of the Arthurian legend of the sword in the stone. I’m self-publishing a new coloring book through CreateSpace on Amazon, which is print-on-demand. There’s plenty for me to do.

Hunter: Your new book The Golden Key is a departure for you as well. Tell me about that.

Ruth: It’s a Victorian fairy tale that I’ve been wanting to illustrate — above all others — for 40 years. I couldn’t figure out how to make it a picture book, because it’s so darned long. I tried to edit it down, but it didn’t work. So we broke it into chapters and made it a novel, with 47 illustrations. I went all out.

Hunter: Had you worked with scratchboard before this project?

Ruth: No — I had done, like, two in my life. But it’s a novel, so I knew I couldn’t do it in full color. And I wanted to use a medium that would do the story justice. My oil paintings run all the way from light to dark. I’m not a timid artist — I focus on the effects of light.

Hunter: The lighting in The Golden Key is so striking. The scenes look almost cinematic.

Ruth: I think that makes me stand out. Almost nobody does scratchboard like this. Well, wildlife artists do — you see a lot of very detailed wildlife art on scratchboard. It’s a chiaroscuro approach. Maybe I was just born in the wrong century.

Hunter: When illustrating people, you’ve said that you often use models. How does that work?

Ruth: Well, everybody knows people! It’s a matter of asking around, and finding friends of friends. Sometimes I’ll just run into somebody on the street and say: that’s a great tattoo — can I do a picture of you?

Hunter: So you’re working from photographs?

Ruth: Yes. I’m exhibiting 17 of my scratchboards at the Manhan Cafe on Cottage Street through the winter. If you stop in at the cafe, you’ll see a picture of a woman with a tattoo on her chest of a winged creature. I met her at the cafe and thought: can I do a scratchboard of someone with a tattoo, and get the light right?

We went to a graveyard in Springfield, where some of the gravestones have an angel figure. I have a picture of her standing behind one, with some flowers, almost like this is one of her ancestors. But she has this tattoo on her chest, and shadowy wings behind her.

That’s the kind of personal work that I was inspired to make by this black-and-white medium. Pictures that I would never dream of doing in oils.

Hunter: The Golden Key is for an older audience?

Ruth: Definitely. I’d say 8 and up.

Hunter: Do you think much about the age of the reader while illustrating?

Ruth: Goldilocks was the first one where I was really thinking about the age of the child, in terms of the style.

Hunter: Do you have conversations with publishers or fellow artists about which styles fit best for different age ranges?

Ruth: No. Each artist thinks about that for each project, to some degree. But what’s great about picture books is that you can do fairly sophisticated pictures for very young children.

These days, publishers seem to want slightly younger-looking styles than they used to. More accessible, childlike, cartoon styles. But my books are still popular at book sales, so I think there’s room for all styles. Some kids like really humorous stories. Some kids are more introverted and dreamy — they enjoy the pictures they can just fall into, and let their imagination take flight.

Grown-ups like all kinds of different books. It’s the same with young children. Then, of course, I have people coming up to me who are in their thirties, and they remember my books from when they were growing up. They say: “this was my favorite book!” and they tell me about growing up with it. That’s what makes this all worthwhile.

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.