On the first page of Fiona Kyle’s dramaturgical notes for Caryl Churchill’s Cloud 9, at Hartford Stage through March 19, is a photo of Margaret Thatcher. The next page features the less- recognizable face of Cecil Rhodes. He was the epitome of 19th-century British imperialism – ruthless exploiter of southern Africa’s diamond fields (and her labor force), prime minister of Cape Colony, champion of Victorian institutions and culture.

His is the spirit that hovers over Act One, a savagely hilarious parody of 1870s colonial Africa and Victorian hanky-panky. And it’s Thatcher who looms over Act Two, which takes place 100 years on, in late-1970s London (though it’s Rhodes’ portrait that haunts the second act, hanging half-hidden on the back wall of the set).

In her notes, Kyle outlines the genesis of this intriguing two-part satire, which began life in a series of workshops and discussions. A group of actors representing a spectrum of sexual identities, together with the playwright and the director of the political theater Joint Stock, explored the “sexual politics” of England in that era and the political aspects of sexuality – and vice versa.

Their conversations and personal histories led back to the Victorian mores and morals that still had weight in mid-century Britain. One chance participant, the rehearsal hall’s caretaker, told of achieving orgasm for the first time in her late middle age, having previously survived an abusive marriage, and reported, “Now I’m on Cloud Nine” – which gave Churchill, the most inventive, audacious and forceful playwright of her generation, the title for her play.

Act One finds a veddy British family on their African estate, smug but restless. The natives in the surrounding villages are restless, too, and in the plantation house there are enough back-stairs shenanigans going on to fill the plot of a sex farce. For example: Clive, the paterfamilias, is secretly in love with the riding-crop-wielding widow from the neighboring farm, while Betty, his wife, is carrying on with Clive’s best friend, a pith-helmeted explorer, who is also getting it on with the family’s slavishly loyal black servant, Joshua. Meanwhile, seven-year-old Edward is girlishly attached to his dolly and his nanny is in love with Betty.

Act One finds a veddy British family on their African estate, smug but restless. The natives in the surrounding villages are restless, too, and in the plantation house there are enough back-stairs shenanigans going on to fill the plot of a sex farce. For example: Clive, the paterfamilias, is secretly in love with the riding-crop-wielding widow from the neighboring farm, while Betty, his wife, is carrying on with Clive’s best friend, a pith-helmeted explorer, who is also getting it on with the family’s slavishly loyal black servant, Joshua. Meanwhile, seven-year-old Edward is girlishly attached to his dolly and his nanny is in love with Betty.

These dangerous liaisons and perversions of Victorian propriety receive a few extra twists in Churchill’s cast list: Betty is to be played by a man, young Edward by an older woman, and Joshua (a caricature of internalized oppression) by a white man. All this adds up to spicy, sassy (and for some Brits in the late ’70s, scandalous) theater that echoed the cross-dressing and gender-bending Charles Ludlam’s Theatre of the Ridiculous was doing in New York at that time, but with a seriousness of purpose underlying the camp.

The play premiered in 1979, the year Margaret Thatcher’s Tory Party took power in Britain, in the midst of widespread labor unrest, which the Iron Lady exploited for electoral gain and then proceeded to exacerbate. While Act Two doesn’t directly address this state of affairs, it does reflect the social upheavals of the time, not least the revolutions of gay rights and women’s liberation.

In Act Two, the same actors appear onstage as different characters, three of them holdovers from the first half. They are grown-up Edward (the unrealistic 100-year timespan is part and parcel of the play’s fantastical structure), his sister Victoria (who was represented by a rag doll in Act One) and their mother, Betty. Edward is gay, as we had already guessed, with a philandering boyfriend.  Victoria is the mother of two, with a floundering marriage and an attraction to a lesbian friend. Betty is finally leaving her husband and discovering the joys of sexual satisfaction for the first time, like the custodian in the play’s early workshop. In this section, all the actors play gender-specific roles but one: the man who played Clive is now Cathy, a bratty little girl.

Victoria is the mother of two, with a floundering marriage and an attraction to a lesbian friend. Betty is finally leaving her husband and discovering the joys of sexual satisfaction for the first time, like the custodian in the play’s early workshop. In this section, all the actors play gender-specific roles but one: the man who played Clive is now Cathy, a bratty little girl.

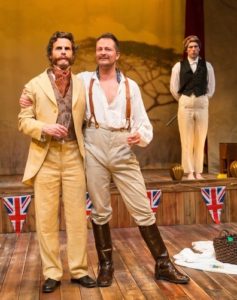

Elizabeth Williamson’s production in Hartford sets the African scenes in an old-time music hall (designed by Nick Vaughn), emphasizing the artificiality and role-playing. Then we transition to a London park with a children’s playground, and the thrust stage is stripped bare to the theater walls for a bit of in-your-face realism.

The contrast, I think, also wants to argue for the show’s up-to-dateness. Hartford’s artistic director Darko Tresnjak says in a program note that “even though sexual mores have changed quite dramatically since 1979, Cloud 9 is just as exhilarating and funny 38 years later” and that “its playful investigation of family, gender and sexuality feels necessary in today’s social climate.”

I was partially convinced of this by Hartford’s production, but not entirely. I’ve seen Cloud 9 several times over the years, and going into this production I recalled Act One quite clearly, but Act Two hardly at all. I think that’s because the first half is so outrageously original and the second half feels so, well, normal. Act Two’s jealousies, flirtations and betrayals still ring true, since human nature never seems to change. The gay relationships in the “contemporary” section may have been challenging in theater at that time – domestic drama turned on its head – but they’re hardly noteworthy now. And perhaps it’s that very normality that makes the second half of the piece less satisfying.

The strong cast handle their contrasting roles with aplomb, even relish. Emily Gunyou Halaas is Betty’s mother in the first half, then her daughter in the second. In Act One, Sarah Lemp plays both the infatuated governess and the sexy widow (which I didn’t even notice till I read the program) and Victoria’s lesbian amour in Act Two. Chandler Williams is the swashbuckling adventurer before the intermission, and Victoria’s discontented husband after. And William John Austin is chilling, in different ways, first as the deceptively faithful servant and then as Edward’s unfaithful lover.

Mia Dillon was a late addition to the cast, after an accident sidelined Kate Forbes during previews, postponing press night for a week.  Despite the hurry-up, she makes a thoroughly convincing job of both the young, doll-cuddling Edward and the older, liberated Betty. Mark H. Dold’s generational switch doesn’t go quite so well. He gives us an amusingly stiff-upper-lipped, ultra-cis-male Clive, but his second-act Cathy is an overdone little-girl burlesque.

Despite the hurry-up, she makes a thoroughly convincing job of both the young, doll-cuddling Edward and the older, liberated Betty. Mark H. Dold’s generational switch doesn’t go quite so well. He gives us an amusingly stiff-upper-lipped, ultra-cis-male Clive, but his second-act Cathy is an overdone little-girl burlesque.

For me, the show’s absolute highlight is Tom Pecinka. He’s Betty in the first act, and it’s one of the most finely drawn and persuasive drag turns I’ve ever seen – funny without going camp, utterly feminine and wholly sympathetic. And in Act Two, he brings an entirely different body, voice and manner to the adult Edward.

This production is also Hartford’s response to, as Tresnjak puts it, “the conversation currently going on in the theatre world regarding opportunities (or lack thereof) for women playwrights and directors.” Churchill’s script and Williamson’s direction add to the sum of opportunities, along with another woman playwright and three more female directors in the company’s seven-play season.

Photos by T. Charles Erickson

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com