As we struggle with tough questions surrounding science today, we could do worse than look for guidance to the great figures of the past.

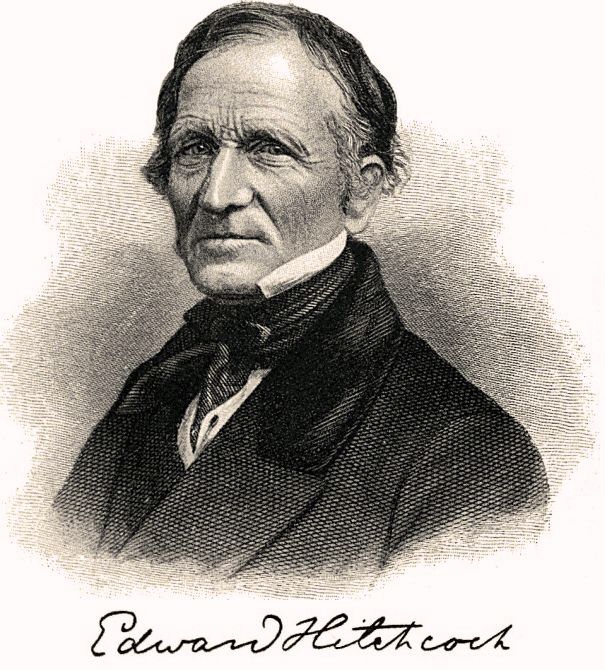

One such figure, it turns out, belongs to our own Pioneer Valley, and many argue he’s received too little attention: Edward Hitchcock, geologist, botanist, minister, teacher, and president of Amherst College from 1845 to 1854.

I first encountered Hitchcock during a field trip as a geology student at Amherst College. We didn’t go far: just to the basement of the geology building, into cool halls below ground. Drawer after drawer held secret texts, printed not onto pages but onto layers of rock: preserved dinosaur footprints, a collection largely gathered and donated by Hitchcock.

Reading about Hitchcock now, I was taken to find that his life and work nearly two centuries ago speak to modern themes: the relationship of science to religion, the importance of citizen science, and the need for an equal role for women in science, reflected in his lifelong collaboration with his wife, the accomplished scientific illustrator Orra White Hitchcock.

Yet, amazingly, this man never earned a college degree. Even more remarkably, until his early 30s, he worked not as a professional scientist but as a high school principal and Calvinist minister. He published his scientific findings as a hobby.

Son of a shoemaker, expected to grow up to work the family farm, young Hitchcock instead sought an education, at Deerfield Academy and with his uncle, astronomer Epaphras Hoyt. Hoyt assigned Hitchcock to collect data on the Great Comet of 1811. The 18-year-old gathered results of high enough quality for publication in a prominent scientific journal.

Later, he explored Massachusetts, by then with Orra White. He discovered a new species of fern. He made the first geologic maps of the state. He identified and studied the traces of an enormous prehistoric lake that once filled the Pioneer Valley, now named Lake Hitchcock in his honor. He discovered fossil fish along the Connecticut River.

He was among the discoverers — and the first to formally scientifically analyze — the first dinosaur footprints ever found. The word “dinosaur” didn’t exist yet, so he identified them as the prints of giant birds — presciently, it turns out, since most scientists now believe birds evolved from dinosaurs.

“I think he’s an underappreciated man of his time,” says Tekla Harms, professor of geology at Amherst College. Charles Darwin, she points out, exchanged letters with Hitchcock, and famous British geologist Charles Lyell visited his home. Even Emily Dickinson studied with him, later including his ideas on rock formation in her poetry.

Hitchcock is about to get a new and more public look at his life in “Impressions from a Lost World,” a new website to debut this summer. Administered by the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, the site explores the history of the dinosaur footprint discovery, including Hitchcock’s pivotal role.

An associated exhibit on the life and work of Edward and Orra Hitchcock will open at the Memorial Hall Museum in Deerfield June 2.

“We’re trying to take the interest in dinosaurs and science, to get people interested in the public questions that swirl surrounding science,” says Tim Neumann, executive director for the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

One of the most contemporary themes Hitchcock grappled with was the relationship of science and religion.

“Hitchcock deserves applause because he was a loner, especially among Calvinist ministers, in finding no conflict between Calvinist religion and science,” says Bob Herbert, professor emeritus at Mount Holyoke College. Herbert, an art historian, has studied Edward and Orra White Hitchcock and contributed to the new website.

Far from taking him away from religion, Hitchcock believed, studying nature brought him to God since the natural world was God’s creation. He felt his life’s work was to reconcile the observable facts he and other scientists saw in the rock record with religious beliefs.

Hitchcock adopted a traditional Catholic view that the days of Genesis were metaphorical, not literal. Each “day” of creation represented a whole eon, allowing for “deep time” before humankind when rocks and fossils accumulated.

More than most ministers and many scientists of his day, Hitchcock was willing to let his religious assumptions be challenged by what he saw in the physical land around him.

“He said, ‘If I can see things the way they really are, it will get me closer to God,’” explains Harms. “It didn’t bother him to say there had been giant birds, it didn’t bother him to say there was deep time, it didn’t bother him to really look and incorporate empirical evidence.”

Hitchcock had his flaws. He was a hypochondriac, Harms notes. Worse, at the pinnacle of his career, he became embroiled in “an unpleasant battle, a priority dispute” over the footprint discovery, says Sarah Doyle, consultant to the Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and principal writer for Impressions from a Lost World.

The first person to notice the prints was a quarry laborer named Dexter Marsh, who showed them to local physician James Deane. The two did some early work on the tracks, convincing themselves that the prints mimicked the stride of an animal like a turkey. Deane took plaster casts and brought the tracks to Hitchcock’s attention, who by then was state geologist.

Hitchcock soon threw himself into study of the tracks, finding and excavating many new specimens. He also asked the editor of the American Journal of Science, who was Hitchcock’s mentor and friend, to publish his report of the findings instead of Deane’s. Hitchcock argued, with perhaps some justification, that his by then extensive geological knowledge brought his article more scientific import than Deane’s.

In the article, Hitchcock did acknowledge Deane’s findings. However, he “gave the back of the hand to his collaborators by not mentioning them often enough or generously enough,” argues Herbert.

The new website chronicles the contributions of Marsh and Deane, including essays on their lives by Herbert. Nearly ten years later, as the fame of the tracks grew, Deane would publish a complaint that he was their true discoverer as “birds” and had been ignored, kicking off controversy.

Marsh, meanwhile, began his own “cabinet” or museum of dinosaur prints, to which visitors arrived from far and wide.

“One of the themes of this period is amateur versus professional,” says Neumann. “When you come down to it, Hitchcock was a brilliant amateur. The other thing is, we’re introducing the common person, like Dexter Marsh of Greenfield. He was a workman, he had his own little business. He was the janitor of the church in Greenfield.”

In the modern era, similarly, “we live in an age when who owns science is a big deal,” says Neumann. “You see it in questions like climate change.”

Despite the simmering conflicts, the ability to contribute to science from all walks of society that marked Hitchcock’s day remains a lesson in our age of specialization.

Across the centuries, Hitchcock’s message still resonates for scientists and ordinary citizens alike. He challenges us to accept the natural world as it is, no matter how surprising – and to learn to use the tools of science and collaboration both to explore it deeply and incorporate it into our worldviews.

“I’m just inspired by Hitchcock as an observer and a man who trusted his observations,” says Harms. “If you just sit down and use your brain, and are honest about what you’re seeing, great things come out of it.”

Naila Moreira is a writer and poet who often focuses on science, nature and the environment. She teaches science writing at Smith College and is the writer in residence at Forbes Library. She’s on Twitter @nailamoreira.