Pablo Picasso often painted himself as a bull.

A fan of attending bullfights in his native Spain, the Cubist master saw himself as the hulking beast with big muscles, wild eyes, and swinging genitalia.

Minotauromachie by Pablo Picasso

In a piece now on view at The Clark in Williamstown, Large Bullfight With Female Bullfighter — a work largely interpreted to feature the artist, his wife, and his lover — the face of the bull is wild with smoothed-back curling hair. His mouth is agape coughing buttons and spewing shit about “doormats and goddesses.” The bull/artist is stabbed through the hump with a long, thin spear that looks like it annoys more than wounds. The hand holding it is scratchy and primitive. Breasts bounce up to the sky. The matador’s neck uncoils like a snake and in the audience is a white bust of a woman’s face that stands in stark contrast to the rest of the inky characters in the arena. (I’d love to share a copy of this print, but copyrights on Picasso’s work are strict. You can, however, see the image here.)

In Picasso: Encounters, a not-to-be-missed 35-piece Clark exhibit focusing on the artist’s printmaking and featuring Large Bullfight, the work displayed seeks to not only showcase Picasso’s art and creative process evident in prints he’s gone back to and developed over time, but also feature the people who worked closely with the artist: his printers and muses.

“There’s this myth about Picasso, that he created everything on his own — the ultimate genius,” said curator Jay Clarke standing before a wall-sized black and white photo at the Clark of Picasso looking over an etching pint, Minotauromachia (1936), with a printmaker.

“He was absolutely a genius,” she continued, “but who are the unsung heroes behind Picasso? Who were the dealers, the printers, the wives, partners, and children — the people who supported him and allowed him to create.”

Picasso, who is said to have sweat machismo, is often seen as a user of women; picking up one and discarding her when he found another he liked better. But that’s not the relationship he demonstrates in the art on display at The Clark.

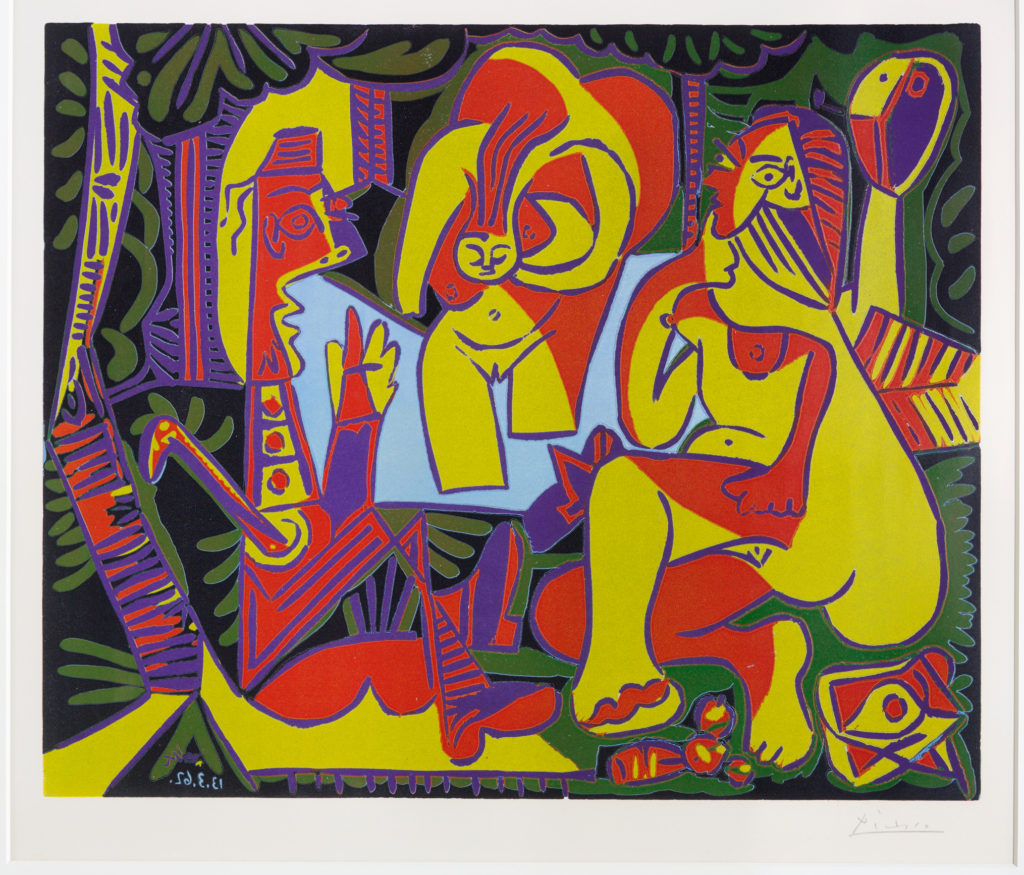

Luncheon on the Grass, after Manet by Pablo Picasso

Picasso needed women — desperately, Clarke said. They had power over him because he depended on them for his home, his care, and his creative muse. That last one must have really chapped his ass, I assume. I can see no other reason why an otherwise intelligent person would say, “For me, there are only two kinds of women — goddesses and doormats” unless driven by fear. (This quote was attributed to Picasso by his longtime lover Francoise Gilot in her tell-all Life With Picasso, which did not reveal an overall flattering profile of the artist.) Picasso didn’t like to be alone, said Clarke noting that he never left a lover or wife without having already begun another relationship. He chased the intoxicating electricity of beginning a new relationship — like a bull.

Large Bullfight With Female Bullfighter (1939) is a intimate depiction of his turmoil during one of those awkward transitional periods between wife and lover. His first wife Olga Khokhlova, a Russian ballerina he often painted wearing a fur collar, is interpreted to be the matador. The bust, smiling like a pigeon in the audience, is his lover, Marie Therese. His wife strikes, but misses the kill spot and ultimately never had a chance of mortally wounding the bull — not with that scrawny body and puny weapon. From the right angle, the bull’s head appears to be splitting, but it’s an illusion; that is just the way he is — half open and wild.

Picasso: Encounters is a revealing look at the artist and his passion. It includes a portrait, Self-Portrait (1901), of the artist during Picasso’s blue period when he was living a Bohemian existence in Madrid. There’s a stunningly deep copy of Picasso’s first large-scale print, The Frugal Repast (1904), which features a gaunt couple etched by hunger. And an historically important print for the Cubist movement, Still Life With Bottle Marc (1912) created at the behest of Picasso’s art dealer to promote his unique style with a cheaper, abundant, print to sell. There are several prints featuring Bull-casso, and others of the faces of his wives and lovers.

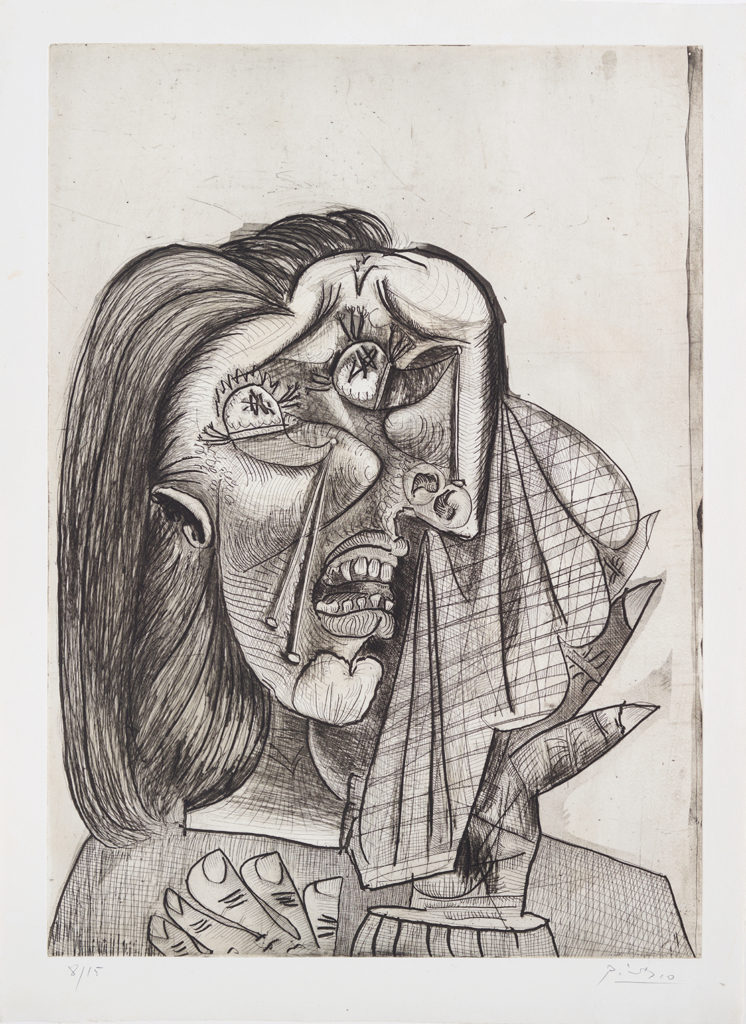

Something art lovers may recognize in the exhibit is The Weeping Woman (1937). Picasso took a distressed woman from his most famous painting Guernica (1937), a mural of tortured people and animals in the wake of the Nazi practice-bombing on the Basque/Spanish town, and began reworking her image, making various prints along the way. The first version of the piece is dark and bold. You can see the woman’s chipped teeth and iron nails coming out of her eyes. By the fourth version of the drypoint etching, her sorrow has been distorted and warped in a way that shows grief has completely consumed her face.

Weeping Woman by Pablo Picasso

Another bright point in the exhibit is Picasso’s reimagining of other artists’ work, something in which he became intensely interested in his later years, Clarke said. His reboot of Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (Luncheon on the Grass, after Manet, 1968), an oil painting of a confidant nude woman hanging out with some fully clothed gents, turns the impressionist work on its head. Gone are the individual brush strokes that gave Manet’s paintings a dream-like quality. Picasso’s Luncheons are hard, definite and bold in their strong colors and lines; compressing Manet’s original concept into a solid print.

Picasso: Encounters will deepen your understanding of Picasso, his creative process, and what made him get up every morning. The exhibit runs through August. Go see it.

Picasso: Encounters: Through Aug. 27. Free for people 18 and under as well as students; $20 for the general public. The Clark, 225 South St., Williamstown. (413) 458-2303, clarkart.edu.