Barry Roberts has heard Massachusetts is facing an energy crisis, but he doesn’t buy it.

Roberts is a commercial landlord who owns several buildings in Amherst including the Amherst Cinema building and the block where Amherst Ice Cream is located, as well as properties in Hadley.

He and some of his clients have had to cut back on business expansion due to the moratorium Berkshire Gas placed on new gas hookups in 2015, Roberts said. But the moratorium was a necessary drastic measure, Berkshire Gas explained in letters to its customers, that was caused by a localized fuel shortage. Until the Northeast Energy Direct (NED) pipeline is built, the company said, it would be unable to provide gas to new customers in the communities of Amherst, Deerfield, Greenfield, Hadley, Hatfield, Montague, Sunderland, and Whately.

He and some of his clients have had to cut back on business expansion due to the moratorium Berkshire Gas placed on new gas hookups in 2015, Roberts said. But the moratorium was a necessary drastic measure, Berkshire Gas explained in letters to its customers, that was caused by a localized fuel shortage. Until the Northeast Energy Direct (NED) pipeline is built, the company said, it would be unable to provide gas to new customers in the communities of Amherst, Deerfield, Greenfield, Hadley, Hatfield, Montague, Sunderland, and Whately.

This means the total usage of natural gas in moratorium towns cannot increase. So, Berkshire Gas is not accepting new customers, and any development projects or remodeling that requires more gas either cannot be completed or must use propane or electric — both of which can be more costly.

It’s been three years since then and energy needs in Massachusetts are declining, in part because of an explosion of residential solar installations that reduce electric grid demand. The NED pipeline was killed in 2016 and Kinder Morgan says it has no plans to resurrect the plan. In 2015 the Massachusetts Attorney General delivered a rebuke of the energy crisis narrative with a 70-page report claiming Massachusetts has plenty of fuel/energy delivery capacity during normal and peak times until at least 2030. The study did not look further beyond that time. Berkshire Gas still has the moratorium in place, however, and Roberts is growing impatient.

“They don’t seem to be too interested in short term solutions,” Roberts said.

In the meantime, Roberts is having to coordinate to bring in more expensive energy-consuming equipment and delay construction. For example, he said, a new office building he’s been working on over on North Pleasant Street ran into problems when it was discovered there was no room to build a propane tank for the building. So, the entire development had to move forward with electric. “This is a perfect example of something that is going to cost us more to build, and the tenants a lot more in utilities,” Roberts said.

In the meantime, Roberts is having to coordinate to bring in more expensive energy-consuming equipment and delay construction. For example, he said, a new office building he’s been working on over on North Pleasant Street ran into problems when it was discovered there was no room to build a propane tank for the building. So, the entire development had to move forward with electric. “This is a perfect example of something that is going to cost us more to build, and the tenants a lot more in utilities,” Roberts said.

Berkshire Gas declined telephone and email requests to be interviewed for this article, but did provide a written statement.

Christopher Farrell, manager for corporate communications and government relations at Berkshire Gas, said the company is still working on how to serve new natural gas customers in Franklin and Hampshire counties, but did not provide details.

“Importantly,” Farrell said, “the company’s resource plan will enable it to continue to provide reliable and safe natural gas service to its existing natural gas customers.”

Filling The Gap Left By Nuclear And Coal

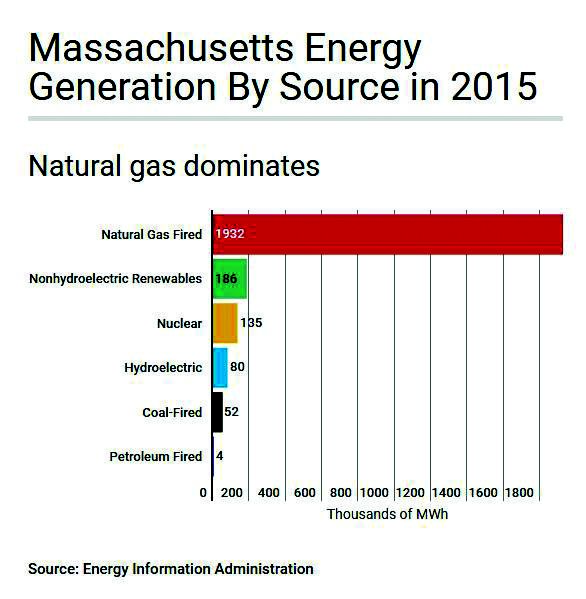

People who push the idea that Massachusetts is in the midst of an energy crisis say the closure of nuclear power and coal-fired plants have left a gap in the state’s energy portfolio that can’t be filled by renewable resources alone — at least not in the short term.

“The Northeast has major energy challenges,” said Stephen Leahy, vice president of policy and analysis of Northeast Gas Association — whose members include both Berkshire and Columbia Gas. “And natural gas is part of the solution, but not the whole solution.”

Leahy said natural gas consumption, used primarily for heating homes, has been rising in the Northeast during recent years. This has been in part due to the state closing several coal-fired and nuclear power plants over the last 10 years. In April, Massachusetts’ energy consumption was derived from 80 percent natural gas (the national average is 29 percent) and 11 percent from renewable energy resources (nation wide, the average is 22 percent).

Leahy says the state’s energy challenges are in part due to the size of natural gas pipelines.

“There are pipeline constraints,” he said. “The pipelines that were built in the 1950s haven’t been enhanced in a big way in a long time. That’s why you see these proposals to bring more gas — to increase the deliverability of natural gas into the region.”

Meanwhile, people who are critical of the energy crisis message point to the AG’s report and say the ability to provide power to Massachusetts people is secure for now, but will need attention along with considered, environmentally-friendly, sustainable actions.

Fran Cummings, a former director of energy under then-Gov. William Weld’s administration (she served from 1995 to 1998) and a member of the Massachusetts chapter of environmentalist group the Sierra Club, said the push for more gas is knee-jerk.

“I don’t think it’s necessary to keep saying, ‘Well, just because we’re going to have less coal and we’re going to have less nuclear, we need more gas,’” he said. “We need something, but it can be renewables, it can be energy-efficiency.”

Berkshire Gas has said in letters to customers that if the NED pipeline is not built, the moratorium would be indefinite. Since 2016, when plans for the pipeline fell apart and Kinder Morgan officially ended its plans to build the pipeline, Berkshire Gas has been left without a clear way out of the gas rations.

This stalemate is hurting businesses. Geoff Kravitz, the director of Amherst Development, said that the moratorium hit Amherst at the worst possible time. Amherst has been going through some serious development in the downtown area and Kravitz said ending the moratorium “would definitely decrease the costs, which would mean lower rents for tenants, either residential or commercial, and lower heating costs.”

It’s “certainly made development more difficult,” he said.

Kravitz said that there have been cases of business opting not to move into the area due to the moratorium.

“There was a microbrewery considering relocating to Amherst and when I told them about the moratorium, they dropped off the map.”

Energy Demand In Decline

Since the Attorney General’s 2015 report, “Power System Reliability in New England,” was issued, energy demand and prices have been on a downward spiral and gas capacity has increased in Massachusetts, said Chloe Gotsis, deputy press secretary for the AG’s Office, citing information from ISO New England.

She said Spectra Energy’s Algonquin Incremental Market Pipeline, which moves gas from New Jersey across Connecticut and Rhode Island, and into the eastern half of Massachusetts, went online in November 2016, and has helped increase gas capacity in the commonwealth.

However, ISO New England, a regional transportation organization that oversees the operation for the bulk of the region’s electric power system and transmission lines, sees problems in the years ahead for power supply in New England. They warn renewable energy sources such as hydroelectric, solar, and wind will not provide the power that fossil fuels can.

Renewable resources provide benefits, said Matthew Kakley, communications specialist with ISO New England, including helping to meet environmental and clean energy goals, but they also pose challenges, including their “intermittent nature and the transmission investments needed to access wind resources in remote areas of New England and hydropower resources in Canada.”

Still, Kakley said ISO New England is working on building a power system that can handle the integration of more renewable generation.

Being Prepared

While an energy crisis may not be gripping Massachusetts right now, it doesn’t mean state, community, and business leaders can sleep on power needs.

State Sen. Anne Gobi, (D-Spencer), who represents parts of Worcester, Hampden, Hampshire, and Middlesex counties, and is a member of the Massachusetts Joint Committee on Telecommunications, Utilities, and Energy, told the Valley Advocate she doesn’t think the commonwealth is heading towards an energy crisis, but does believe the state should be looking at changes in how it generates its energy.

“I know that there are a lot of companies that would like to see natural gas come into the area, but with that there’s a lot of environmental concerns that I have — one, you’re going to put pipeline in.”

Gobi said she’s not a pipeline proponent because she’s seen proposals for projects that cut through rural and environmentally sensitive areas.

Gobi said she’s not a pipeline proponent because she’s seen proposals for projects that cut through rural and environmentally sensitive areas.

“I just don’t think that’s good for Massachusetts and especially in these areas where we have some very pristine open space,” she said. “Seeing a pipeline proposed in those areas is a problem for me.”

Cummings, a director of energy under Weld, said she doesn’t think the commonwealth will be facing an energy crisis at any time soon.

“It’s not like we’re falling asleep and about to get run over by a truck or a tidal wave or something that we didn’t anticipate,” he said. “People are acting and I don’t see any reason why we can’t use cleaner energy than natural gas.”

Cummings also noted that the addition of new natural gas pipelines doesn’t mean Massachusetts’ supply would increase. A lot of pipelines that have been planned for New England, he said, are designed to lead to exports of gas.

“So, pipelines would go to [liquified natural gas (LNG)] facilities, which would turn the gas into LNG, and put them on LNG ships to Europe or anywhere in the world,” he said. “Most of that pipeline argument is not about New England.”

A Zombie NED? Kinder Morgan Says ‘No’

After the NED pipeline was withdrawn by Kinder Morgan in May 2016, many environmentalists have speculated that the project may return in the future.

For some town officials in Ashfield, where part of the pipeline was slated to go, the idea of the NED being resurrected is a major concern. It’s part of the reason why the nearby protests at Otis State Park have gotten so intense. Even a small win for the natural gas and pipeline companies could lead to a snowball effect of decisions against the environment.

For some town officials in Ashfield, where part of the pipeline was slated to go, the idea of the NED being resurrected is a major concern. It’s part of the reason why the nearby protests at Otis State Park have gotten so intense. Even a small win for the natural gas and pipeline companies could lead to a snowball effect of decisions against the environment.

“I’ve always said that it was a zombie NED; that it was taken off the table for a moment of time,” Ashfield Select Board member Ron Coler said. “I think in today’s political environment they’re feeling pretty bullish about taking this precedent here [in Otis State Forest] and applying it to the state.”

However, Richard Wheatley, a media liaison with Kinder Morgan, refuted this claim.

“The Northeast Energy Direct Pipeline project is not being placed in an open season. It is not being revived at this point,” he said. “We have other projects in the area that we’re considering … An open season is merely a solicitation that pipeline companies use to determine interest in the market place.”

All this stunted action has put many in limbo. Short terms solutions are becoming more important as it appears long term solutions will be slow coming.

Two proposed solutions have been the installation of a new pipeline in the Pioneer Valley, or a expansion of an existing liquefied natural gas storage facility in Whatley. However, neither solution has seen much resolution.

In April of this year State Sen. Stan Rosenberg (D-Amherst) and five other legislators signed a petition to force Berkshire Gas to hurry up with figuring out a solution to the moratorium. The petition, citing an expert witness who testified that Berkshire could “lift the moratorium this year” with infrastructure upgrades and better use of its storage plant in Whately, said that the moratorium could be closed without building a new supply line.

When asked if she thought the idea of an energy crisis was manufactured, Gobi replied, “I’m not going to say that it’s manufactured. Obviously, if I was in the pipeline business I would want to see more pipeline. I think that it’s just natural that the industry would promote what’s in its best interest.”

Contact Chris Goudreau at cgoudreau@valleyadvocate.com, and Christin Howard at christinhowa@umass.edu.