During the summer 12 years ago, I interned at Science News, a national magazine that reports on science for the public. As a young and inexperienced writer, part of my reporting included visiting the offices of my more experienced colleagues to ask them what good ideas I might fruitfully pursue.

“Write about hurricanes and climate change,” said Janet Raloff, a writer I deeply admire to this day who’s now a Science News editor. “I think that topic’s going to be huge.”

From what I’d already read and heard, it sounded intriguing to me, too. I dived right in.

It was my last big article for the summer. I wasn’t quite finished with it by the end of my internship, so I took it home with me from Washington, D.C., to complete.

I learned in my reporting that scientists were already warning with increasing urgency that climate change could make a big difference for hurricanes. They were discovering, for instance, that a warmer climate would likely cause more rain to pour out of major storms, because hotter air holds more moisture.

They had noticed a significant increase in very strong hurricanes — categories 4 and 5 — as the climate warmed, along with an overall decrease in weaker, category 2 and 3 storms. While the total number of hurricanes wasn’t likely to change, the ones we’d get, their findings suggested, would be nastier.

Twelve years ago, scientists were already cautioning me that while climate change would probably increase hurricane strength, the biggest problem wouldn’t be storm size. Poor urban planning in vulnerable areas would make the impact of big storms far worse than it had to be, they said.

Rising coastal populations, poor building codes, destruction of green space and wetlands that absorb excess water, sprawling asphalt and concrete that make water a rushing menace — these, I was told, would combine with increasingly ferocious storms to make hurricanes more expensive and deadly.

Finally, tired out by the hard work of reporting and writing a complex story, I filed it in August of 2005, glad to have finished.

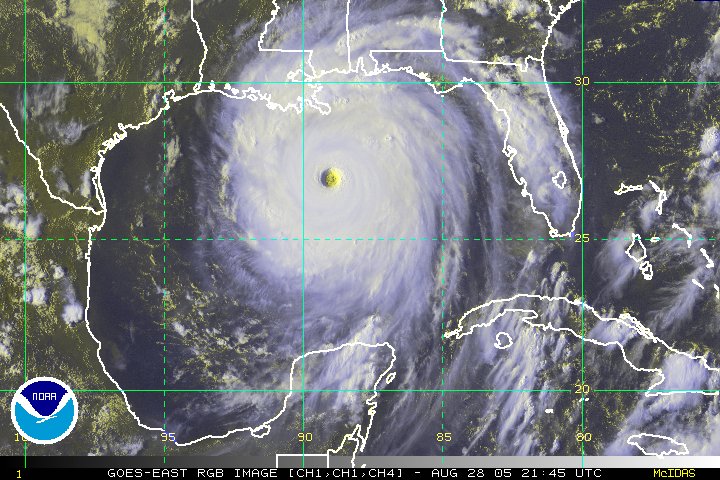

Within days, before my article could see print, Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans.

My article draft came right back to me. “Fix it,” said my editors. “Obviously it’s got to be updated to talk about Katrina.”

I didn’t have to change the science. I called back the researchers I’d already talked to, asking them to comment on the monster storm that cost 1,833 lives and $160 billion in property damage.

As Houston begins the hard work of cleanup in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, as portions of the city still lie underwater, as Harvey is predicted to cost even more than Katrina, it’s frustrating to think just how many years scientists, urban planners and environmental journalists have been warning of the increasing likelihood of just this kind of event.

Just like Katrina, Harvey should have weakened as its size began churning up colder water from deep in the Gulf of Mexico. But just like in 2005, unusually warm waters were present unusually far down in the Gulf. Instead of moderating the storm, the deeper waters strengthened it.

As scientists predicted, warmer-than-normal air also increased the storm’s capacity to absorb and then dump out water. Hurricane Harvey was so big it actually began to take up water it had already rained out, like a giant washing machine circulating its contents around and around.

Could a storm of Hurricane Harvey’s size happen without climate change? Sure, if all the right factors just happened to come together. But that’s the thing with probability and statistics. Normally, we’d expect to get a Harvey maybe once every 1,000 years, according to findings from the Cooperative Institute of Meteorological Satellite Studies.

In a world with climate change, we had Hurricane Katrina, and now here’s Harvey, already pummeling the Gulf Coast again just 12 years later. That’s not to mention the oddity of 2012’s Hurricane Sandy, farther north than hurricanes normally travel. And Hurricane Irma, one of the Atlantic’s strongest hurricanes ever recorded: which, like Katrina in 2005, wasn’t yet even a gleam in the Atlantic’s eye when I started writing this article just a few days ago.

We’re making a world, in other words, where the unusual has become normal. Where a Hurricane Harvey or Irma shouldn’t surprise us anymore. And that’s a result of a climate changed by human activity.

Some have recently tried to mute climate scientists and others, accusing them of “politicizing” Hurricane Harvey in bringing up the role of climate change.

But we don’t call it “politicizing” tragedy when we call out a hospital, say, whose poor safety protocols are leading to premature deaths. Harvey is almost exactly the same thing. As a society, we’ve instituted poor, shortsighted, flawed protocols relative to our climate safety. And our collective refusal to fix our practices, just like in a bad hospital, is causing victims to suffer.

As Hurricane Sandy helped prove, this isn’t a topic of concern only to the typical hurricane belt in the south. Storms in New England, too, are now pouring out rain in larger bursts, threatening flooding and property damage. In the last half century, the amount of water falling during the northeast’s heaviest storm events has increased 70 percent, says Richard Palmer, director of the Northeast Climate Center at the University of Massachusetts.

My senior colleague at Science News, Janet, never called me up to say, “I told you so.” And I didn’t congratulate myself for taking her up on her article idea. In fact, even more than a decade ago it was becoming very clear that climate change and hurricanes were locked in a dangerous, toxic relationship. Janet and I didn’t invent anything, we just followed our reporting noses to a growing story.

Climate scientists and science reporters shouldn’t be criticized for speaking out on what they’ve learned about the earth and its systems. Indeed, it would be criminal for them to say nothing.

In the face of intimidation and attack, they’ve been trying to warn us for a very long time.

Naila Moreira is a writer and poet who often focuses on science, nature and the environment. She teaches science writing at Smith College and is the writer in residence at Forbes Library. She’s on Twitter @nailamoreira.