You wouldn’t think a library would be a likely setting for high drama, but here we are with two playing at once. In Hartford, Sharon Washington is telling the story of her girlhood, when she lived, not virtually but literally, in a library. And in West Springfield, another real-life tale focuses on a political battle over racial insinuations, led by a librarian.

Alabama Story, we’re told at the outset, is “the story of a story” — a children’s storybook, or to be precise, the pictures in that book. Kenneth Jones’s play is a real-life fable about how a couple of make-believe rabbits stirred up a human hornet’s nest. It’s at the Majestic Theater through Feb. 11.

The work at issue is The Rabbits’ Wedding, a picture book written and illustrated by Garth Williams in which the title characters frolic with their animal friends in the forest and then get married. And there’s the rub. The girl bunny’s fur is white and the boy bunny’s is, gasp, black. Gasp, that is, in 1959 Alabama, when Jim Crow (most definitely not a fuzzy storybook figure) is being put to flight by the escalating Civil Rights Movement.

Williams himself is a character in the play, narrating the story of how a die-hard segregationist state senator had the book banned for its supposed race-mixing message (a meaning its astonished author denied) and was defied by the principled state librarian.

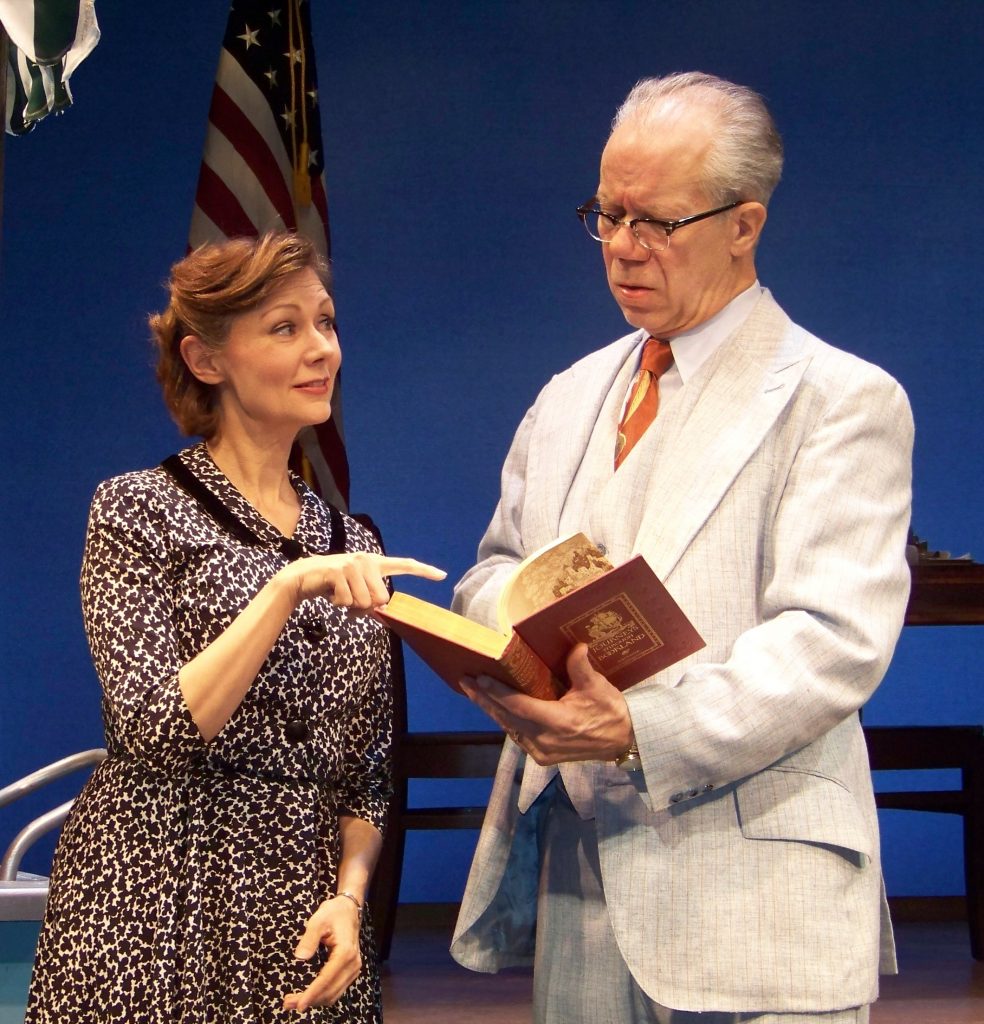

In Sheila Siragusa’s spirited production, Cate Damon winningly portrays the librarian, Emily Wheelock Reed, a starchy, bespectacled lover of literature and scourge of censorship. Her loyal assistant is played by Jack Grigoli with an unflappable geniality that pairs nicely with Damon’s crisp practicality.

The challenge to the book is led by State Senator E.W. Higgins (a semi-fictionized version of the real-life E.O. Eddins), a pillar of the White Citizens’ Council, who is also one of the library system’s biggest boosters (one of the script’s few nuances). In Rand Foerster’s expansive performance, he’s a jovial, garrulous good ol’ boy whose slap on your back could have a knife in it. Mark Dean nimbly plays the author/narrator, and all the supporting characters, too, notably a colleague of the senator’s who shares his solid Confederate credentials but sees the wind of history shifting and counsels bending with it instead of spitting into it.

In a parallel subplot, we meet Joshua and Lily, who were best friends as children. His (black) mother worked as housekeeper for her (white) mother, and they played together with the carefree innocence of storybook creatures until a traumatic moment drew the color line between them. Now, meeting again as grown-ups, they are hesitant, wary, and in her case in denial about what happened back then. While he’s become a civil-rights activist, she has settled into a comfortable obliviousness. For me, these episodes don’t really work, and Silk Johnson and Melenie Freedom Flynn struggle to give life to the contrived thematic parallels and the stilted dialogue.

Daniel D. Rist’s set adroitly represents both the library building and the state capitol, flanked by towers of books and overarched by an imposing marble pediment, and costumer Dawn McKay provides a fitting parade of fifties fashions.

Considering its subject, the playwright’s treatment of this all-but-forgotten slice of history might seem too simplistic, even corny, but it couldn’t be more timely in the current climate of hostility to difference, truculent ignorance, and desperate resistance to change.

Feeding the Dragon

As in Alabama Story, Sharon Washington frames her autobiographical narrative as a storybook tale. Her childhood was, indeed, the stuff of fairytales, both their magic and their perils. The engaging one-woman show is playing at Hartford Stage through Feb. 4.

Washington grew up in the sixties and seventies on New York’s Upper West Side, where her father was custodian of the New York Public Library’s St. Agnes branch. She and her parents lived in a spacious apartment on the building’s top floor, and after hours little Sharon roamed freely through the stacks, reading voraciously and imagining herself a princess in her own private palace.

The first-person narrative is spiced with portrayals of relatives and neighbors, above all her parents, her mother’s sharp-tongued Noo Yawkese counterpointing her father’s comfortable South Carolina drawl.

The title of the 80-minute piece is Feeding the Dragon, referring to her father’s most essential duty — tending the building’s huge coal-burning furnace, a fiery, insatiable monster. It also reflects the dark side of the childhood idyll, her father’s alcoholism, the dragon that regularly consumed him.

Race doesn’t play a key role here, but Washington reads us excerpts from black authors who have inspired her, and evokes W.E.B. Du Bois’ “double consciousness” when she becomes the black scholarship kid in a privileged Upper East Side private school.

Tony Ferrieri’s stage is a set of platforms and stairs resting on rows of books. It’s backed by a wall of lighted panels whose colors, in Ann Wrightson’s inspired design, shift in tune with the story’s scenes and moods. In one of the play’s most thrilling moments, Sharon’s mother desperately revives the furnace her drunken father has neglected, and the background lighting mimics the fire’s slow recovery into a blazing inferno.

While Washington isn’t the most versatile of solo performers — apart from the parents, her renderings of the supporting characters are often too physically and vocally similar. But she’s an enormously personable storyteller, with a supple voice, lively hands, and expressive face, welcoming us with passion and humor into the fairytale castle of her memory.

Chris Rohmann is at StageStruck@crocker.com and valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann