Barb Hadden walks about the white walled Oxbow Gallery on Pleasant Street, contemplating the placements in her show at the Northampton artist collective.

With two galleries, artist-members have a show in the large front gallery and a show in the back gallery. Hadden’s show is in the front gallery and it is her last.

“I can’t figure out how long I’ve been a member at the Oxbow,” she says perplexed. “About 10 years maybe… or maybe it’s 12.” But she describes the gallery as “a beautiful space, and it shows paintings at their best.”

Her show Thoughts on the Education of Daughters at the Oxbow Gallery in Northampton is visually sparse but thick with meaning. Which is a perfect representation of Hadden herself.

Hadden is an artist’s artist; clad in workaday clothes and a good nature, she is quick to laugh and expresses herself in an unadorned fashion. Although she is neither tall nor physically expansive, there is a rangy quality about her. And it comes as no surprise that she loves the outdoors; it is her silent but inextricable partner in the world.

Hadden is a finely educated artist, and as a photographer she has often chosen trees as her subjects. Her selenium silver images are largely dedicated to capturing the tangle of limbs and branches one finds in the forest.

And these tangles also reflect the artist; talking to Hadden about her work is much like walking into a cluster of trees. The subjects of her conversation seem discrete and separate, but upon closer examination, you realize they are bound by a web of interconnected roots.

The trees also afford her protection from outside forces and the forces within. In her conversations, Hadden broaches the subjects of singleness, reproduction, aging, lesbianism, romance, and danger. But her photos and previous paintings deal with the natural world, not the human condition.

Even when her subjects are human, Hadden’s figures remain seminal parts of the landscapes; there’s her desire to marry the human form with its surroundings and the environment. There’s also the desire to recreate situations through which she can live vicariously.

From the title of her show, which is also the title of 18th century feminist Mary Wollstonecraft’s conduct book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, to the inspiration for her most recent paintings, the Title Nine catalog, Hadden’s binding thread throughout is the limitations of femaleness.

Although the Title Nine clothing retailer is named after the landmark 1972 federal civil rights law that, in part, cleared the way for increased athletic opportunities for females, it represents a mythical world for most women. A world that they can only dream about.

Hadden describes Title Nine catalog as “a funny periodical” whose photos of tawny, happy athletic women served as inspirations for her Thoughts paintings. But it dawned on her that there was more to it than an appreciation for good photography that drew her in. “I realized I wanted to do those things–hiking, biking….It’s great to be able to put yourself in the picture.”

Hadden was once a part of the “picture” and still spends time outdoors; she’s a house painter when she’s not creating art. But she was also in the thick of it, at one time. A part of the trees she photographed.

“I used to love going hiking a lot. I went when I was 18 or 19. I did the first quarter of the Long Trail (part of the Appalachian Trail in Vermont) but it got really creepy ‘cause of the guys….I didn’t feel safe, so I stopped doing it.”

Perhaps in response to that imposed limitation, Hadden eventually saw the vignettes in the Title Nine catalog as an escape; she says that in spite of the “funny” aspects of the photos, she “actually wanted to be on the beach or in the snow on a mountain. These are cultural pictures to put ourselves in.”

As a result, the subjects of her paintings are not only outdoors, they are truly meshed with the landscape. She explains it this way: “They (the persona and the environment) are not on a separate plane.”

To match the complexities in her inner world, Hadden is honest about her creative process and openly admits it’s neither clean nor tidy, and it “takes months to resolve an image.” She adds, “the process mirrors how I live and make sense of life: I make mistakes, struggle with communication, get into trouble.”

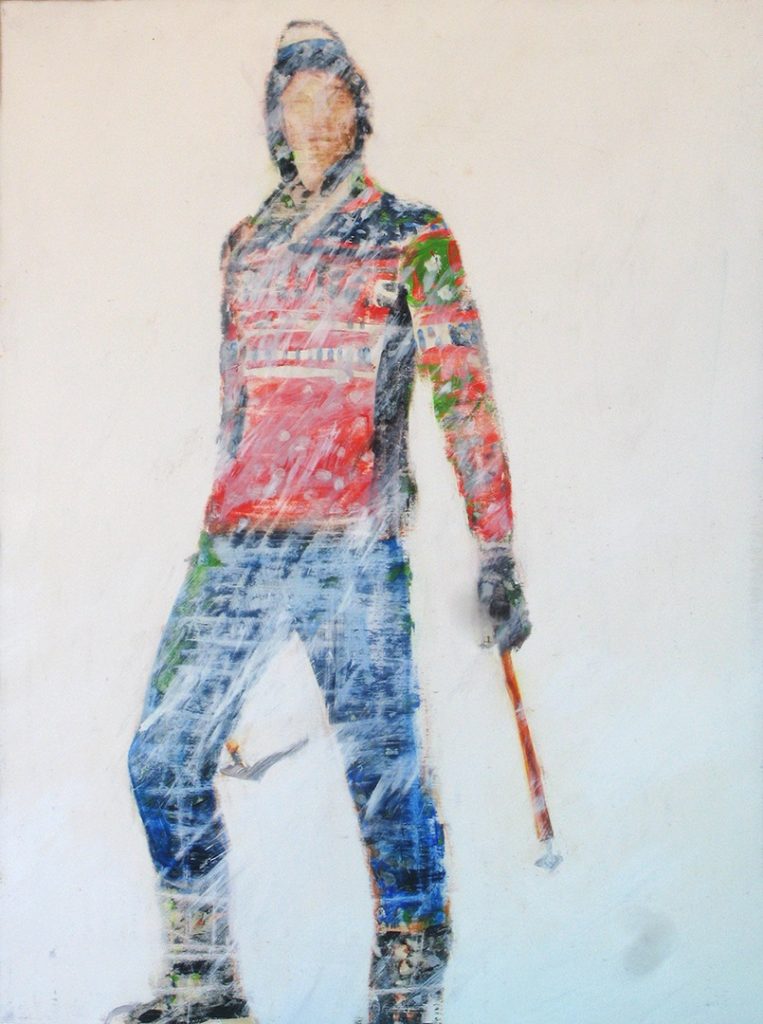

That admittedly untidy process makes for some compelling work; Hadden’s paintings are organic, honest and open. There is an ephemeral quality to her paintings.

The painting, “Snowman” is “a direct quote from the Title Nine catalog,” and a combination of two realities. The majority of the painting is black, but lacquered to provide sheen and nuance. The outline of a woman in a bikini holds the reins of a snow white horse.

Snowman, the horse, was an animal who was saved from slaughter by a man who taught it to become a champion. And although “Ty”, the woman from the Title Nine catalog is just an outline, Snowman is fully realized–beautifully and realistically crafted.

The rest of the painting is void of any landscape which makes “Ty” truly mesh with the “landscape. But the figure manages to be as powerful as the horse. A remarkable feat in black, white, and a few imperceptible colors that make up her outline.

Another, Paper Ocean, is the ocean, the horizon line, and sand. Placed on top of the landscape is a female figure walking with energy and purpose. The woman, however, is conjoined with all of the elements of the shore through tightly knit horizontal lines that run through both the figure and the water. Hadden achieves the oneness with the environment.

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters is a terrific show, but it becomes even more stellar, like most shows, when the artist is there to fill in the blanks and guide the viewer to their own conclusions.

It’s too bad that Hadden’s tenure at the Oxbow is over, but it’s difficult to believe her depth of thought and her experiences will cease to find their ways into the world through art. As Hadden says, “The older I get, the more I live and the more I actually learn…I’m really amazed.”

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters. The Oxbow Gallery. April 5 thru 29, 2018 Thursday – Sunday from 12-5 p.m. Reception, Friday, April 13th 5-8 p.m.