Nowadays, Stratford-upon-Avon feels not so much like a town as a gift shop. The once-sleepy hamlet where William Shakespeare was born some 450 years ago, which he abandoned for a life on the London stage, has become a mercantile monument to Stratford’s most famous son – which must seem ironic to the “anti-Stratfordians” in the Shakespearean authorship controversy, who can’t credit the notion that an uneducated bumkin from a provincial market town could have penned these transcendent masterworks.

In any case, Stratford is the natural home for the Royal Shakespeare Company, which operates two stages in a majestic modern building, completely remodeled in the aughts, fronting the swan-crowded Avon River. Earlier this month I spent a day there with two blood-soaked tragedies – Macbeth, a key fixture in the canon, and The Duchess of Malfi, by John Webster, a younger contemporary of Shakespeare’s and a master of gory Jacobean revenge drama. (You might remember him as the creepy street urchin in Shakespeare in Love who says his favorite play is Shakespeare’s bloodiest, Titus Andronicus.)

The two shows have different casts and directors, but have a lot in common besides their high body counts. Both are performed on bare platform stages thrusting into the audience, providing patrons with a chillingly intimate experience (in the second half of Malfi, protective covering is distributed to the front rows, à la Blue Man Group, in preparation for the blood-spattered climax.)

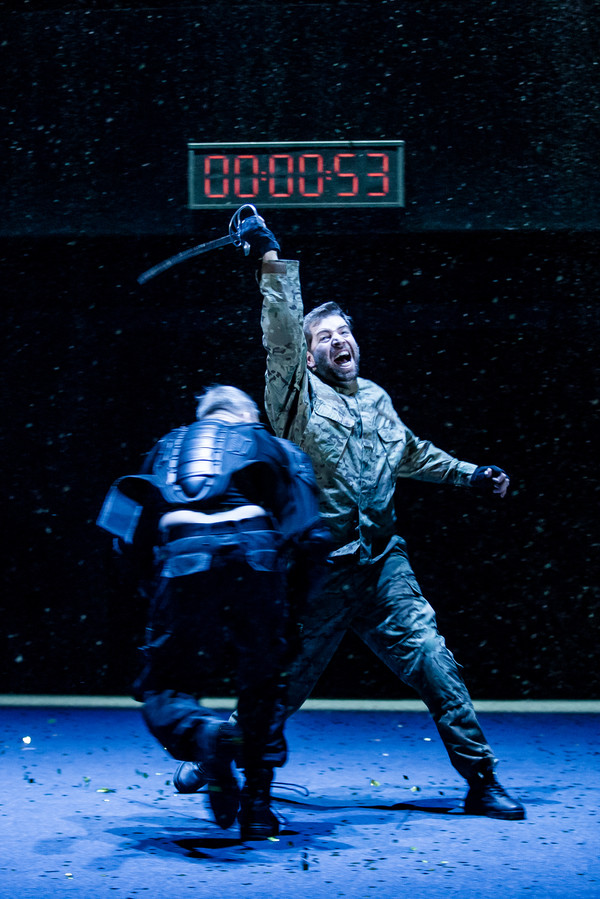

Both adopt a kind of mod-Gothic look – eclectic contemporary garb in spare, shadowy spaces, with period weapons. Both heighten their dramatic moments with bone-shaking sound and music. Both approach their grisly subjects with an ironical detachment. Both compress their onrushing action into two breathless hours. Both are directed by women, as are all the plays in the RSC’s current season. Both are mightily intriguing and pretty strange.

Macbeth is the one about the Scottish war hero who, goaded by prophecies, ambition and a nervy wife, kills the king to take his throne and then goes on killing in order to keep it. In director Polly Findlay’s vision, Scotland is a dark, surreal dreamscape. The witches who foretell Macbeth’s rise to power are three little girls in pink polka-dot jammies, clutching bloody dolls and speaking their lines in a vacant monotone – perhaps avatars of all the play’s dead children.

Macbeth is the one about the Scottish war hero who, goaded by prophecies, ambition and a nervy wife, kills the king to take his throne and then goes on killing in order to keep it. In director Polly Findlay’s vision, Scotland is a dark, surreal dreamscape. The witches who foretell Macbeth’s rise to power are three little girls in pink polka-dot jammies, clutching bloody dolls and speaking their lines in a vacant monotone – perhaps avatars of all the play’s dead children.

The Macbeths’ household is overseen by a laconic caretaker (Michael Hodgson) – Shakespeare’s Porter, here not so much drunken as disenchanted – who patrols with a carpet-sweeper, chalks a running tally of killings on the wall, and stage manages the later murders and battles as he humorously (!) signals the actors to get on with it.

He also cues a large digital clock that begins counting down at the moment of Macbeth’s first homicide and comes to 0:00 at the moment of his death. In one corner of the set stands a water cooler, never used that I noticed, and above the stage, marking the play’s inexorable progress, fragments of lines are projected – The future in the instant / Fears and scruples shake us / What’s done cannot be undone.

He also cues a large digital clock that begins counting down at the moment of Macbeth’s first homicide and comes to 0:00 at the moment of his death. In one corner of the set stands a water cooler, never used that I noticed, and above the stage, marking the play’s inexorable progress, fragments of lines are projected – The future in the instant / Fears and scruples shake us / What’s done cannot be undone.

Christopher Eccleston’s Macbeth is a blunt, bluff military man who delivers his speeches with more impatience than reflection. His assertive swagger only occasionally cracks with uncertainty – even the moment of his death is a decision, when he finally gives in to the weight of circumstance and mocking prophecy and offers his neck to Macduff’s avenging sword.

Lady Macbeth’s usual dramatic arc runs from steely resolution to suicidal madness, but in Niamh Cusack’s performance she’s pretty neurotic from the outset – a chattering, simpering hostess to the about-to-be-murdered king, a gleeful co-conspirator showing her bloody fingers to front-row spectators, a newly invested queen reveling in pomp and power but tottering on unaccustomed high heels. Finally, when she’s sleepwalking in guilty remorse, unable to wash the blood from her hands, she’s dressed not in the standard flowing nightgown, but silk pajamas – perhaps in sisterhood with those child-witches in onesies.

Macho gone mad

The Duchess of Malfi is a tense, claustrophobic tale of sexual obsession and violent jealousy in which an independent-minded young widow flaunts tradition to marry her social inferior and pays for it with her life. The night I was there, the title role was taken by an understudy, Amanda Hadingue, who gave the part a proud, brittle energy, a fierce determination to obey her own will and defy her enemies.

Those adversaries are her own brothers, a Cardinal (Chris New), who’s incensed at her secret unsanctified marriage, and Ferdinand (Alexander Cobb), who wants her for himself. In their efforts to discover and slay the duchess’s lover (Paul Woodson) they are abetted by her double-dealing servant Bosola (Nicholas Tennant), a cynical ex-con who does their dirty work with stoical detachment (there’s death by stabbing, strangling and a poisoned Bible) before a crisis of conscience turns his knife against his employers.

Those adversaries are her own brothers, a Cardinal (Chris New), who’s incensed at her secret unsanctified marriage, and Ferdinand (Alexander Cobb), who wants her for himself. In their efforts to discover and slay the duchess’s lover (Paul Woodson) they are abetted by her double-dealing servant Bosola (Nicholas Tennant), a cynical ex-con who does their dirty work with stoical detachment (there’s death by stabbing, strangling and a poisoned Bible) before a crisis of conscience turns his knife against his employers.

Maria Aberg’s production is the epitome of high-concept. Where Webster’s critique is of moral corruption in aristocratic circles, Aberg’s attention is on testosterone-fueled male domination. The set, by Naomi Dawson (one of an all-female design team), is backed with monkey-bar scaffolding suggesting a gymnasium. From this gloomy enclave emerges a squad of sweaty men, the embodiment of toxic masculinity, who execute a heavy-metal dance routine and later become a “wild consort of madmen” sent to intimidate the duchess.

The setting also evokes an abattoir. The partly dismembered and emasculated carcass of a bull is suspended from a chain on one side of the stage. At the beginning of the second half, forecasting the coming litany of slaughter, Ferdinand slits it open and blood pours out, oozing over the stage until every footprint is red and every dead body in the corpse-strewn climax is soaked with it (thus the front-row blankets).

The setting also evokes an abattoir. The partly dismembered and emasculated carcass of a bull is suspended from a chain on one side of the stage. At the beginning of the second half, forecasting the coming litany of slaughter, Ferdinand slits it open and blood pours out, oozing over the stage until every footprint is red and every dead body in the corpse-strewn climax is soaked with it (thus the front-row blankets).

A program note stresses the production’s focus on “masculinity and madness,” to draw connections between power and violence, entitlement and extremism, even sports and militarism, “and how this resonates with the violence and brutality we see on a daily basis around the world.”

Macbeth runs in Stratford until September 18, then plays at the Barbican in London from October 15 to January 18 2019. The Duchess of Malfi closes this weekend, but also on the Stratford stages are Romeo and Juliet and The Merry Wives of Windsor – both running into September before moving to the Barbican – and Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine, August 16-December 1.

Macbeth photos by Richard Davenport

The Duchess of Malfi photos by Helen Maybank

© Royal Shakespeare Company

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email StageStruck@crocker.com