There’s a party going on in the basement of Chelle and Lank’s house – an unlicensed after-hours drink-and-dance dive in inner-city Detroit. That is, until a police raid on a similar establishment explodes into violence and the neighborhood goes up in flames.

Detroit ’67 is the first, and weakest, of Dominique Morisseau’s trilogy of plays known as the Detroit Project. The current production, through March 10 at Hartford Stage Company, is a collaboration with the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, NJ, where it played last fall. First produced in 2013, this is the play’s first outing in this area. The second in the cycle, Paradise Blue, debuted at Williamstown Theatre Festival in 2015, and Skeleton Crew had its New England premiere at Chester Theatre Company in 2017.

The trilogy looks at black lives in Morisseau’s hometown during three different eras – a smaller-scale echo of August Wilson’s monumental ten-play Pittsburgh Cycle. Each of the plays captures a turning point in the Motor City’s history and a moment of crisis for the African-American community. Paradise Blue takes place in a 1949 jazz club in the city’s historic Black Bottom district that’s threatened by gentrification. Skeleton Crew unfolds in the break room of a present-day auto-assembly plant on the verge of closure. Detroit ’67 is set against the backdrop of the deadly riots in the summer of 1967. (In an interview included in the Hartford program, the playwright tells us that some locals use the term “the Great Rebellion” in preference to the pejorative “riots.”)

In all three, Morisseau’s focus, like Wilson’s, is on black life in itself, with few white characters and only glancing reference to the white world. Their predicaments may be impacted, even dictated, by society’s racism, but the day-to-day connections and conflicts occur among themselves. Here the connections are between Lank (named for Langston Hughes) and his widowed sister Chelle (short for Michelle) and with their respective best friends, Sly and Bunny.

In all three, Morisseau’s focus, like Wilson’s, is on black life in itself, with few white characters and only glancing reference to the white world. Their predicaments may be impacted, even dictated, by society’s racism, but the day-to-day connections and conflicts occur among themselves. Here the connections are between Lank (named for Langston Hughes) and his widowed sister Chelle (short for Michelle) and with their respective best friends, Sly and Bunny.

The conflicts arise, first, over Lank’s determination to use the small nest-egg he and Chelle inherited from their parents, in order to acquire a legit bar that’s for sale in the neighborhood – he ambitious to improve his lot, she skeptical of his plans and committed to insuring her son’s education. (This plot point takes us right back to themes in Lorraine Hansberry’s groundbreaking A Raisin in the Sun.) The conflicts mount when Lank and Sly encounter a young white woman on the street, beaten and disoriented, and Lank gives her refuge in the basement – which sets off all of Chelle’s alarm bells.

The cinder-block walls of Riccardo Hernandez’s set are hung with posters – Joe Louis, Malcolm X – and strung with Christmas lights to give the basement a festive air. It’s an underground space in more than a literal sense, touching on both the illegality of the improvised night spot and the semi-secret currents of black life in a white-dominated world.

Morisseau’s dialogue is pitch perfect in the jostling back-and-forth of jokes and squabbles, but it can get a bit stilted in moments of self-reflection or self-assertion. The second act is punctuated with monologues in which characters express principles and passions we’ve already gleaned from their interactions, as if the points need to be formally stated. The plotting, too, is often heavy-handed. Making this all the more evident, the director, Jade King Carroll, has encouraged, or allowed, her cast to oversell almost every moment.

Carroll’s otherwise energetic, well-paced production fields a supple cast of Hartford Stage newcomers. As Lank, Johnny Ramey shows a tough tenderness that helps us believe he would rescue a white damsel in distress – and fall for her from the look in her eyes. Myxolydia Tyler, who starred in Well Intentioned White People last summer at Barrington Stage, is affecting as Chelle, whose very name suggests the brittle shell she’s built around her feelings, a defense against the hostile world outside as well as the insistent courtship of Lank’s friend Sly.

Carroll’s otherwise energetic, well-paced production fields a supple cast of Hartford Stage newcomers. As Lank, Johnny Ramey shows a tough tenderness that helps us believe he would rescue a white damsel in distress – and fall for her from the look in her eyes. Myxolydia Tyler, who starred in Well Intentioned White People last summer at Barrington Stage, is affecting as Chelle, whose very name suggests the brittle shell she’s built around her feelings, a defense against the hostile world outside as well as the insistent courtship of Lank’s friend Sly.

To that role Will Cobbs brings a hip swagger that fits his street smarts but fails to amuse Chelle. Nyahale Allie is blowsy, bosomy Bunny, decked out in shimmering gowns (by costumer Dede M. Ayite) and fashion wigs (by Leah J. Loukas) that scream “party girl,” a holler aimed particularly in Lank’s disinterested direction.

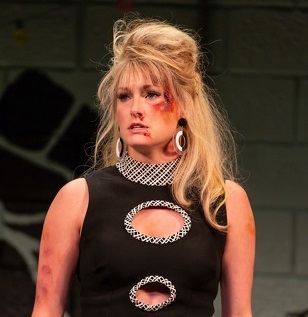

Bunny, and to some extent the white woman, Caroline, are more dramatic devices than fully fleshed characters – Bunny as a banter-buddy for Chelle, Caroline as a means of bringing the outside world, with its ever-present dangers, into the basement sanctuary. Ginna La Vine gives us a rather implausible white person, not only “unprejudiced” but almost instantly comfortable in these alien surroundings.

Bunny, and to some extent the white woman, Caroline, are more dramatic devices than fully fleshed characters – Bunny as a banter-buddy for Chelle, Caroline as a means of bringing the outside world, with its ever-present dangers, into the basement sanctuary. Ginna La Vine gives us a rather implausible white person, not only “unprejudiced” but almost instantly comfortable in these alien surroundings.

Even more than the violent Rebellion, which brought troops and tanks onto the city’s streets to quell it, Detroit in the Sixties is remembered as the cradle of Motown, the music that flavored the era and floats through the play. We first see Chelle coaxing a skipping 45-rpm record through the Temptations’ “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” (Morisseau is also the librettist of the jukebox musical about the Temps, Ain’t Too Proud) before Lank and Sly equip the makeshift nightclub with the latest in hi-fi technology – an 8-track player.

The stereo pumps out familiar hits from the likes of Smokey Robinson and the Four Tops, Martha and the Vandellas and Mary Wells. In fact, the chosen tracks are, and were, so mainstream that it rings a little false when Lank is surprised to discover that Caroline knows them too – though perhaps it’s meant to signal the chasm of contact between the races.

For all its sometimes awkward plotting and speechifying, Detroit ’67 is a potent piece of work, a time capsule that also serves as a reminder of the dangers that still stalk African Americans on our cities’ streets and, with its jaunty Motown soundtrack, that even in times of crisis there are moments of joy, even hope.

Photos by T. Charles Erickson

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com