Each year, high school students across the country see uniformed members of the armed forces within school walls offering information on how to join up. But a local organization asks the question whether these soldiers are overselling a dangerous career path to an audience whose brains are still developing.

The Resistance Center for Peace and Justice, a Northampton nonprofit, has published three editions of a report called “Military Recruitment in Western Massachusetts High Schools,” which authors claim to be the first record of military recruitment activity in the region’s schools. Authors accuse recruiters of emphasizing financial and travel incentives while downplaying the risks of psychological disorders, job insecurity, and sexual trauma.

Jeff Napolitano is executive director of The Resistance Center for Peace and Justice, in Northampton. Photographed at the center on Thursday, March 21, 2019. Kevin Gutting photo

Resistance Center Executive Director Jeff Napolitano, 40, said recent efforts to curb military recruitment efforts are not tied to his organization’s pacifist leanings.

“This is not about being in opposition to the military,” he said. “It isn’t even about being anti-war. Why are we allowing the military, which is a pretty serious thing, to solicit children in a vulnerable environment, in an unsupervised space? In a place of learning, of all places.”

“These are kids,” added Miranda Groux, 23, program coordinator at the Resistance Center. “They’re so susceptible to making choices that might not serve them well if they’re manipulated.”

Military recruiters, however, say they are offering an option available to students after graduation, and stressed that no one is forced to follow the advice of visiting recruiters.

“Every student I’ve made a connection with obviously had their own best interests in that connection,” said Sgt. Maj. David O’Dea, an Army official in the office that oversees recruitment efforts in the region encompassing Western Mass. “They’re no more forced to listen to us than they are their English teacher or their history teacher.”

Writing the report

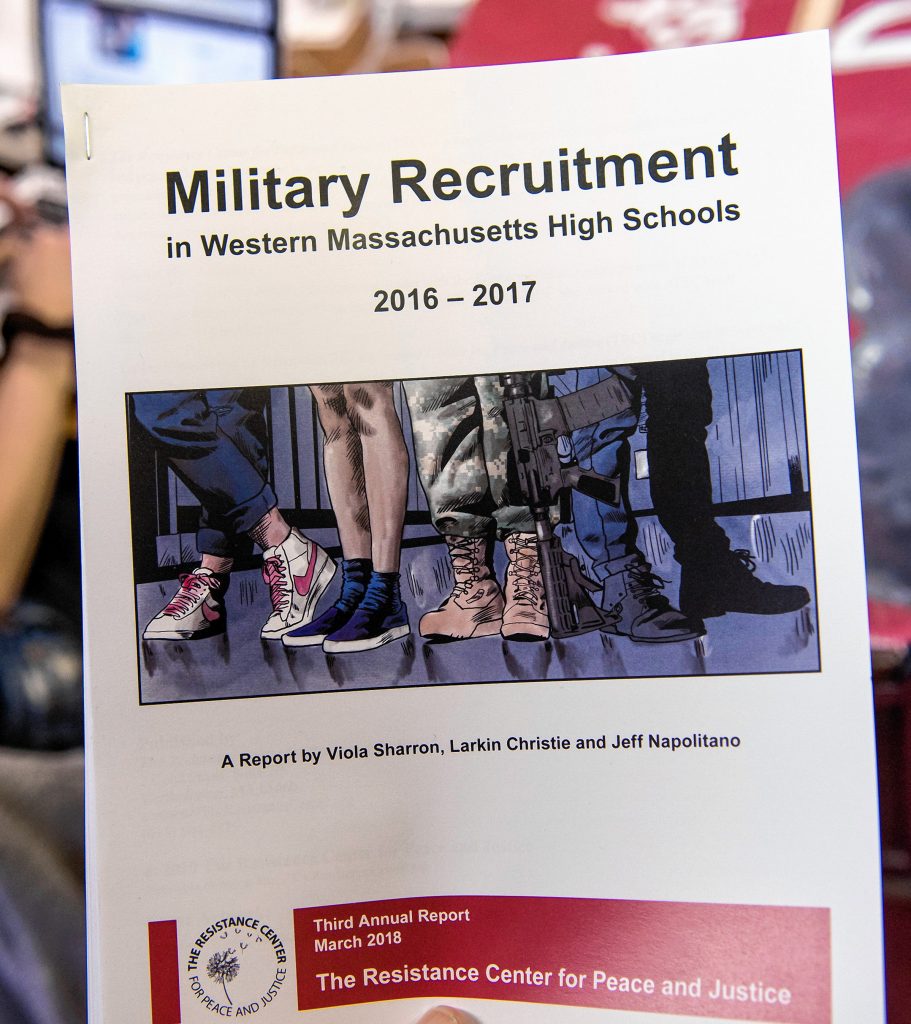

Military Recruitment in Western Massachusetts High Schools 2016-2017, a report by The Resistance Center for Peace and Justice, in Northampton. Photographed on Thursday, March 21, 2019. Kevin Gutting photo

The 97-page Resistance Center report contains survey responses from schools in Hampshire, Hampden, Franklin, and Berkshire counties. Schools were sent a list of questions, seeking information such as dates and branches of military visits, the specific location of the recruiters within the school, and if students were left alone with the soldiers. The survey also asked when and how schools distributed forms to allow students to decline, or “opt out” of having their contact information sent to the Department of Defense.

Since 2001, the No Child Left Behind Act requires public schools to give recruiters from the military, colleges, and employers equal access to students and provide the defense department with students’ contact information, if requested. The Resistance Center’s report alleges that with these mandates in place, recruitment efforts have grown — a claim disputed by the military and that could not be confirmed by school administrators.

The report acknowledges that No Child Left Behind gives military recruiters a legal right to visit public schools, but lists recommendations for school administrators to limit contact between soldiers and students. These include requiring faculty or staff supervision during military recruiter visits, keeping detailed records of visits and having a written policy for recruiters that is sent home to parents.

Publishing the report, authors say, is an attempt to inform the public and hold schools and the military accountable. The most recent edition, the third, was published in March 2018 and contains data from the 2016-2017 school year. The Resistance Center is now working on a fourth edition.

“Nobody else in the country is doing this sort of report,” Napolitano said.

Other data requested for the Resistance Center’s report included whether schools host a Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps program, also known as JROTC, and whether the Armed Forces Vocational Aptitude Battery (ASVAB), a standardized test to determine suitability for service, is made available. The report alleges that the ASVAB gives the military access to students’ private information, and that the JROTC programs shape young minds in misleading ways.

“Our schools are no longer just about education, they are sites of exploitation by the Pentagon,” the report reads.

Miranda Groux is program coordinator for The Resistance Center for Peace and Justice’s Military Recruitment Report. Photographed at the center in Northampton on Thursday, March 21, 2019. Kevin Gutting photo

The Resistance Center’s report criticizes military recruiters’ regard for students’ privacy and quotes language said to be from a recent United States Army Recruiting Command school recruiting handbook, advising recruiters to have some students go through yearbooks and provide phone numbers and email addresses of their peers.

The same language is cited in a 2011 study titled “Should We End Military Recruiting in High Schools as a Matter of Child Protection and Public Health?” published in the American Journal of Public Health, and is attributed to a U.S. Army recruitment handbook published in 2006.

When the Advocate asked for a current recruiting handbook, military recruiters said there is not one available. The handbook did not appear to be available on the army’s recruiting website.

Out of the 51 schools surveyed for the most recent Resistance Center report, 33 responded.

Based on the responses, the reports’ authors assigned letter grades to the schools, from A to F. According to the report, the most weight was given to whether students were provided with opt-out forms, the frequency of military visits, if the ASVAB is administered, and if there is a JROTC program.

On recruiter visits, many schools provided dates and branches, some schools listed the branches without specific dates, and some responses were vague, such as “varies.” Grades were affected by what the report’s authors deemed a lack of transparency and record keeping. Schools that did not respond were given an “F.”

“We realize that public schools are not operating with an abundance of resources,” the report reads. “Nevertheless, interaction between school youth and the most advanced and well-financed military institution in the world merits monitoring.”

The only school given an “A” was Amherst-Pelham Regional High School, which reported no military visits in the 2016-2017 school year and claims to not administer the ASVAB.

‘The perfect target audience’

Napolitano said vocational schools are of particular concern because of high graduation rates — a high school diploma or equivalent certification is required for military enlistment — and because students are trained in skills that could take them straight into a job, as opposed to college. He also noted that vocational schools often have higher populations of students from low-income families who may not be able to afford college.

“For military recruiters, vocational school students are sort of the perfect target audience,” Napolitano said.

Smith Vocational and Agricultural High School in Northampton received a grade of “B” in the Resistance Center’s report. According to the school’s survey response, the Army, Marines, and National Guard each had one visit during the school year. The visits were overseen by several school administrators, including the principal and assistant principal, and students were never left alone with recruiters. The ASVAB was not administered.

According to the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education website, 32.9 percent of Smith Vocational students are at an economic disadvantage.

Andrew Linkenhoker, the superintendent of Smith Vocational, said in an email to the Advocate that the school does not favor any post-high school option — industry, college, or military — over another. He said the process for military recruiters to visit the school is the same as for college admission counselors: Recruiters from all organizations reserve a table that is only visible in the cafeteria during lunches.

“Our students are gaining valuable skills at Smith Vocational and we want to ensure all options are available to them upon graduation,” Linkenhoker wrote, adding that college recruiters outnumber military recruiters in the school’s cafeteria.

Smith Vocational typically has 5 to 8 percent of its students enter the military upon graduation, he said.

Rebecca Bard, guidance counselor at West Springfield High School, said she cannot say whether recruiting efforts changed since No Child Left Behind. She joined the school’s guidance department in 2011 — 10 years after the law.

West Springfield also received a “B” in the Resistance Center’s report. According to the school’s survey response, the dates of military visits were not recorded, but recruiters were allowed to request a table during lunch. The answer given to who oversaw the visits was “administrator on duty.”

Bard said in her experience, military recruiters do not meet one-on-one with students to discuss enlistment without a parent or guardian present.

Unlike many schools surveyed, West Springfield does not set a deadline for returning opt-out forms. The school district gives the ASVAB.

Bard described her experience with military recruiters in the school as positive.

“Additionally, I have had quite positive experiences with the administrators of the ASVAB exam on-site and would consider their follow-up interpretation of score reports as un-biased toward the military and very much civilian-career-exploration based,” she wrote in an email.

She provided the Advocate with military service rates among graduates of the past three years: 5 percent of the class of 2018, 4 percent in 2017, and 3 percent in 2016. She said in addition to those who enlisted, she also had a few students who hoped to pursue Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC) in college.

“For some students, the military offers great opportunities,” Bard wrote.

Northampton High School received a grade of “C.” According to its survey response, the Air Force, Navy, Army, National Guard, and Massachusetts Air National Guard each had one 30-minute visit during the school year. The visits are said to be overseen by the “Registrar/Counselors” and take place in the school guidance office. Students are left alone with recruiters in the guidance department conference room, according to the report. The ASVAB is offered, with usually about 10 students signing up, according to the survey.

According to Napolitano, Northampton High School received a lower score based on imprecise data reporting — the school responded with an approximate percentage instead of an exact number when reporting how many students took advantage of “opt-out” forms, for example.

Northampton Public Schools Superintendent John Provost said about 1 percent of Northampton High School students have post-graduation plans that include military service, and more than 90 percent of graduates plan to further their education.

“Our primary mission will always focus on helping students connect with college and careers,” he wrote. “For a small number of those students, access to military recruiters is important.”

Provost noted that adolescents are faced with a number of life decisions, including taking on student debt and signing contracts.

“I think they are always wise to seek the counsel of trusted adults before making any commitments,” Provost wrote.

No set script

Requests to speak with military recruiters in the Valley were redirected to soldiers at the Watervliet Arsenal, near Albany, N.Y. The office oversees school recruitment efforts in the Pioneer Valley and other parts of the Northeast.

The soldiers interviewed were unable to review the Resistance Center’s report. A military spokeswoman said Army security did not permit its viewing on government computers. The Advocate told the soldiers of some of the criticisms in the report.

Sgt. Maj. David O’Dea, left, and Lt. Col. Eric Treschl, Commander, Albany Recruiting Battalion, work at the Watervliet Arsenal near Albany, New York. Contributed photo from Michaellyn Perkins, United States Army Recruiting Command Public Affairs

Sgt. Maj. David O’Dea, 47, has served for over 23 years — having enlisted at age 24 — and said he has had no combat deployments. He said he enlisted because of the educational opportunities available. He now has an associate degree in general studies, a bachelor’s degree in general studies with a minor in psychology and a master’s degree in communication and leadership. He noted that his daughter used his GI Bill for her own education, and now has a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Colorado in Colorado Springs.

“In other words, the Army financed my daughter’s degree, and she does not serve,” O’Dea said.

On the same call was Lt. Col. Eric Treschl, commander of the Albany Recruiting Battalion. Treschl, 50, enlisted 29 years ago for money after college. First, the Army paid for him to earn a bachelor’s degree in psychology.

“Once I got that degree, it opened up opportunities,” he said. “It became less and less about money and more about serving the greater good.”

He now has three master’s degrees: one in management and leadership, another in military arts and science and the third in military operational art and science. Places he has served include South Korea, Kuwait, Iraq, and Afghanistan.

O’Dea and Treschl said visits to schools are different each time, depending on factors such as the school, the recruiter, and the size of the audience.

“We don’t have a set script,” Treschl said.

O’Dea said while some schools have table setups, as many Valley schools reported to the Resistance Center, other schools host classroom presentations or activities with athletic departments.

Treschl said he is not aware of recruiters downplaying the risks of enlistment.

“Our job is inherently risky,” Treschl said. “That’s part of our profession.”

He said families of prospective recruits often ask about PTSD, and acknowledged the risk.

“We are getting better as a profession to deal with and to treat PTSD, but just because you join the military, not just the Army, but the military, does not mean you’re going to get PTSD,” Treschl said.

Between 11 and 20 percent of veterans who served in operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom experience PTSD in a given year, according to the United States Department of Veterans Affairs. The department reports that 12 percent of Gulf War veterans and 15 percent of Vietnam veterans experienced PTSD.

Both Treschl and O’Dea disagree that recruiting efforts have changed specifically as a result of No Child Left Behind in 2001.

“The whole world has changed since 2001,” Treschl said, naming the introduction of the iPhone and social media.

The Resistance Center report criticized social media use, providing an example of an unsolicited message to a high school student describing “awesome reserve bonuses … up to $20,000 if you qualify,” and jobs available in mechanical, medical, and aviation fields.

O’Dea and Treschl were not familiar with the example shown in the Center’s report, but confirmed the Army uses social media in its recruiting efforts.

“Before 2001, recruiters were told they have to go where the people are at. Since 2001, social media is where the people are at,” O’Dea said. “It’s no longer the pizza joint. Now, it’s somewhere on a digital platform. So, absolutely, we take advantage of social media, like anyone else does.”

Counter recruitment

Seth Kershner, a Berkshire County resident, co-authored the book, “Counter-Recruitment and the Campaign to Demilitarize Public Schools.” Kershner, 37, said counter-recruitment, or efforts in opposition to recruitment into the armed forces, is made difficult by cultural norms in favor of the military.

“Part of counter-recruitment is to push up against that and get students to think critically,” he said.

Counter-recruitment efforts, which date back to the Vietnam War era, include visiting schools and presenting alternative options for students who cannot afford to go to college. Kershner said he is not advocating for removal of military recruiters from schools, but what he describes as “common-sense rules and regulations,” such as placing a cap on the number of military recruiter visits.

“Counter-recruiters are not seeking to replace one form of marketing and propaganda with another,” he said. “They try to get students to think critically about militarism and the military’s role in society and in their schools.”

Kershner interviewed Napolitano for his book, published in 2015. Kershner said he obtained thousands of pages on school recruiting by filing Freedom of Information Act requests to the military, but that he had to wait over a year for his requests to be fulfilled. He noted that the military keeps more specific records than the schools.

“Schools don’t know how many times they’re coming; that’s not their job,” he said. “If they don’t have a policy in place, there’s virtually no reason for them to keep track.”

The data he received from the military, Kershner said, showed some Springfield high schools to get an average of 90 Army visits in the 2012-2013 school year.

In the Resistance Center’s report, the High School of Commerce in Springfield and Springfield Central High School were the only schools of those who responded to the survey that answered “yes” to having a JROTC program. Both schools received a grade of “D.” Emails to administrators of both schools were not returned.

Kershner said military recruiters give particular focus to schools with high populations of students who are not white, and both the High School of Commerce and Springfield Central fit that description, according to state records. Both contain student populations with between 60 and 80 percent designated as economically disadvantaged.

Kershner graduated college near the start of the Iraq War. He said he was drawn into counter recruitment. He started by visiting schools as an activist, but around 2010, changed his focus to research — which he acknowledges some readers may expect to show bias.

“I came out of an activist background, but the sourcing that [co-author] Scott [Harding] and I use in our research, I don’t think anyone can argue with that,” he said. “We’re going by what the military says in their own records.”

A veteran perspective

Rob Wilson, formerly the executive director of the Veterans Education Project in Amherst, said schools should present information about military service in an objective manner that encourages critical thinking among students.

“You can join the military when you’re 18, so the time to start learning about this is when you’re in high school,” he said “Unless the law changes, the recruiters will be there.”

Wilson is now a volunteer for the Veterans Education Project, which, among other initiatives, brings veteran speakers into classrooms, where they share their individual experiences. Providing opportunities to hear from veterans and active service members who are not recruiters is one way Wilson believes schools can educate young people about the military.

“I think it’s very useful for students to understand what it means to go into the military and possibly go to war,” he said. “They have to understand more than what they’re learning in textbooks or from movies or from video games and comic books. All of those, in different ways, can glorify war, and just about any veteran, no matter what his political perspective, will tell you war is something that shouldn’t be glorified.”

Wilson emphasizes that the Veterans Service Project does not try to encourage or discourage students in regard to enlistment.

Another way he said schools can educate students on military service is through literature, suggesting The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien, Redeployment by Phil Klay and What Every Person Should Know About War by Chris Hedges. He said his organization recently worked with a high school that hosted veteran speakers shortly after the senior class read The Things They Carried.

“I just think it’s important for teachers and parents to try to provide different points of view, and not to be agenda-driven,” Wilson said.

Activist roots

Napolitano has for a decade been encouraging students to consider alternatives to joining the military. In 2009, he became director of the American Friends Service Committee of Western Massachusetts, housed in the building that now holds the Resistance Center. The local chapter of the Quaker organization was established by local activist Frances Crowe in 1968 to provide counseling in resistance to the Vietnam War.

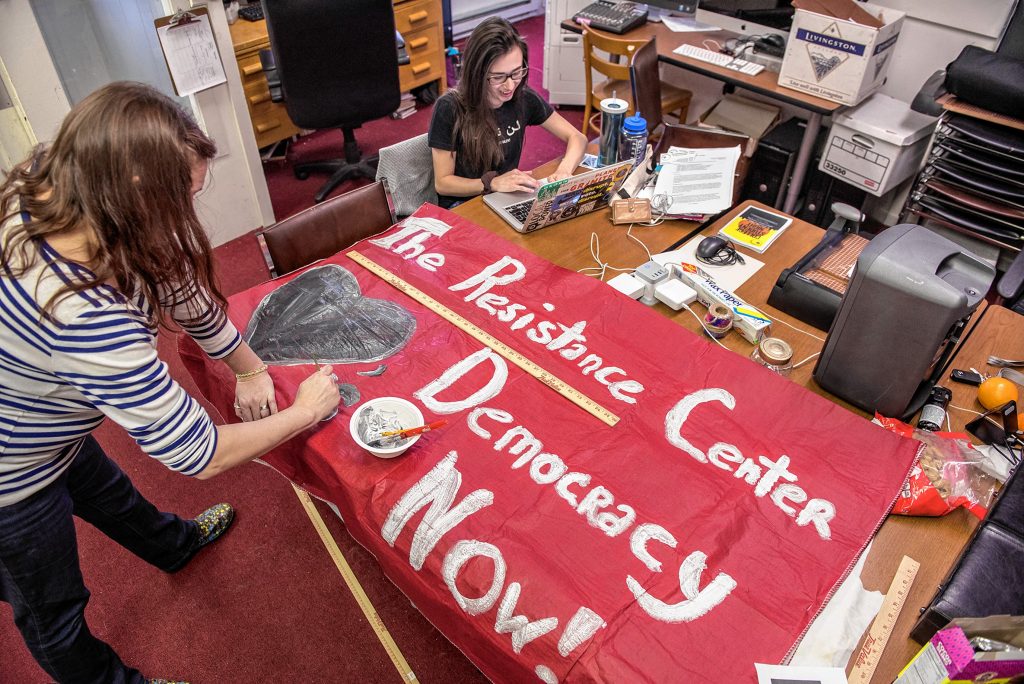

Tara Bernier, left, office manager for The Resistance Center for Peace and Justice in Northampton and program coordinator Miranda Groux prepare for a talk by journalist Amy Goodman at John M. Greene Hall on Thursday, March 21. The Resistance Center has published three editions of a report questioning whether military recruitment in high schools is appropriate. Kevin Gutting photo

Napolitano and his colleagues set up tables in school cafeterias, where they pitched alternatives to joining the military. They brought in lists of labor apprenticeships that young adults could enter with only a high school diploma.

But after only being able to reach so many students at three to five schools during 20-minute lunches, Napolitano began to consider a new approach.

“We were going in, but we didn’t really have a sense of what we were going into,” he said.

To get a sense of military recruitment activity, the local American Friends Service Committee began surveying all of the public schools in the four counties of Western Massachusetts. The first edition of the report was published in March 2015.

The Resistance Center’s Conz Street office still pays homage to its roots as the organization founded by Quakers, members of a religious society known for its pacifist values. Across one wall is a painted image of a tree, bearing the words “Another world is possible/On a quiet morning I can hear her breathing” and a logo for the American Friends Service Committee. The local chapter closed in September 2017.

Groux said she and her colleagues are hoping the information in the report will attract the attention of parents and teachers. The next step would be convincing school officials to further limit the military’s access to students.

“We need to remind ourselves that it is not just another option for kids, at all,” she said. “There are tremendous risks involved with the military that have to be considered when we talk about the military as another choice for students.”