Two plays now on Broadway for limited runs, a world classic and a world premiere, revolve around fractured families whose dynastic dreams turn sour. One involves the ambitious daughters of an English king, the other the ambitious wife of a former U.S. president. Neither ends well.

Hillary and Clinton

Lucas Hnath is interested in what-ifs. In his last Broadway outing, A Doll’s House, Part 2, he asked, What if Ibsen’s Nora returned home 15 years after famously slamming the door on her arid marriage? Now he has turned to contemporary America, three years after the door was abruptly slammed on Hillary Clinton’s political career.

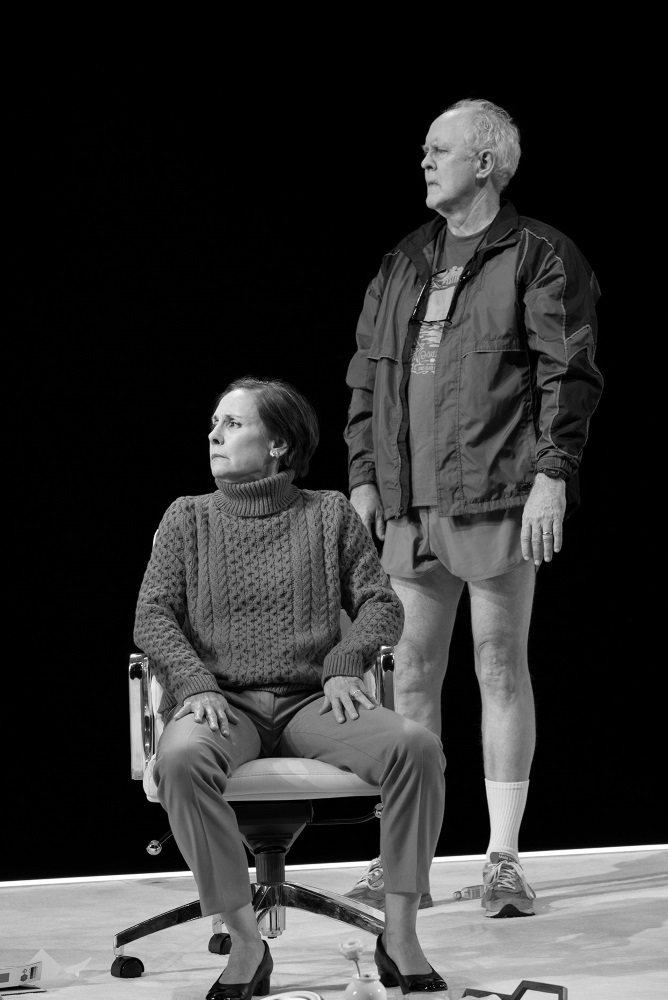

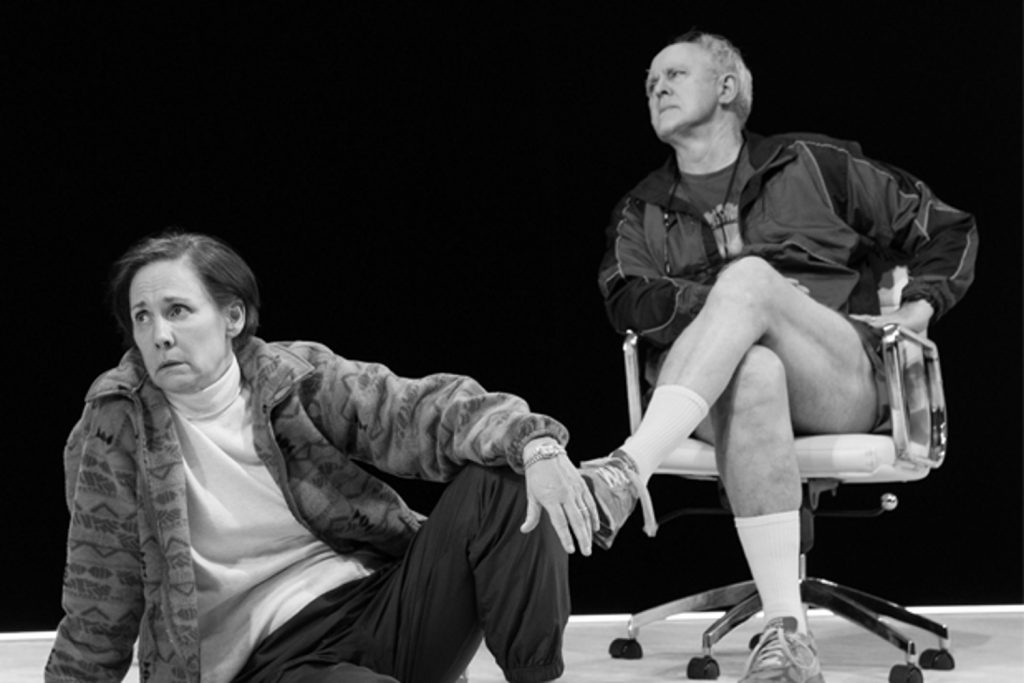

Hillary and Clinton, playing through July 21st, is a sideways slant on a bit of contemporary history, slyly suspended between earthbound reality and the cosmic plane. It takes place in 2008 in a New Hampshire hotel room that, in Chloe Lamford’s set – a white cube backed by infinite blackness – suggests a way station to the afterlife.

At the outset, the wonderful Laurie Metcalf (who played Nora in Hnath’s Doll’s House and won the Best Actress Tony) addresses the audience. Tossing a coin and pondering the laws of probability, she wonders, What if the universe contains more than one reality, more than one outcome to any given circumstance? What if everything that could happen here, does happen somewhere else, over and over? What if, for instance, the presidential aspirations of a certain politician, whom we might call Hillary Clinton, had an infinity of possible results?

At the outset, the wonderful Laurie Metcalf (who played Nora in Hnath’s Doll’s House and won the Best Actress Tony) addresses the audience. Tossing a coin and pondering the laws of probability, she wonders, What if the universe contains more than one reality, more than one outcome to any given circumstance? What if everything that could happen here, does happen somewhere else, over and over? What if, for instance, the presidential aspirations of a certain politician, whom we might call Hillary Clinton, had an infinity of possible results?

As we’re mulling that over, she enters the hotel room where one of these Hillarys is facing a likely defeat in tomorrow’s primary, at the hands of an upstart challenger named Barack. When her husband, Bill, arrives to “help out,” politics gives way to a domestic quarrel in which the subject is still politics but the subtext is who needs who the most – the ultimate co-dependent power couple.

Hnath’s intention, and director Joe Mantello’s, is not to recreate onstage the Clintons we know, but to project them through an altered lens. Neither Metcalf nor John Lithgow, who plays Bill, makes any attempt at impersonation (in a recent interview, Lithgow remarked, “The minute you do an impression, you’re in a Saturday Night Live sketch”). No pants suit for Hillary, who’s in baggy sweats, and Bill is in gym shorts.

But the personalities are there: Hillary’s intense, goal-directed focus, underlaid here with a wide-eyed sense of dread; and Bill’s waggish charm, plus, in Lithgow’s entertaining performance, the man’s pouting resentment at no longer being the center of attention.

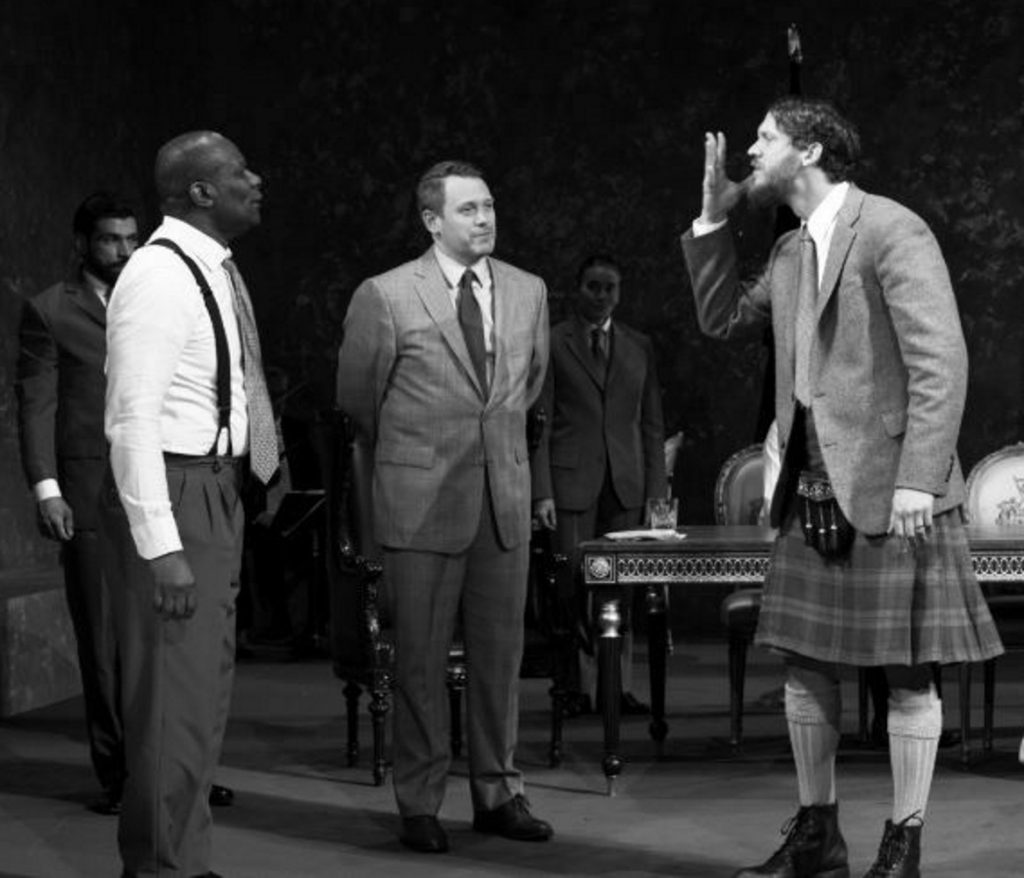

These two are joined briefly by Hillary’s anxious campaign manager, Josh (a prickly Zak Orth) and by Barack (a smooth-talking Peter Francis James) who comes to offer her the vice-presidential spot on the ticket if she drops out now. Barack’s arrival sparks the play’s sharpest moment, as the Clintons drop their heated quarrel and pivot seamlessly into politician mode and an elaborate mutually improvised lie.

These two are joined briefly by Hillary’s anxious campaign manager, Josh (a prickly Zak Orth) and by Barack (a smooth-talking Peter Francis James) who comes to offer her the vice-presidential spot on the ticket if she drops out now. Barack’s arrival sparks the play’s sharpest moment, as the Clintons drop their heated quarrel and pivot seamlessly into politician mode and an elaborate mutually improvised lie.

As we know in our real world, Hillary won the New Hampshire primary (and after Super Tuesday made the same VP offer to her opponent) but lost the nomination. And though the play takes place in a version of 2008, it’s also about 2016, when she won the nomination and then lost the election – the multiverse spinning infinite variations, except for the one in which she wins.

King Lear

Glenda Jackson doesn’t do things by halves. Since her return to the theater in 2016 at age 80, after a 25-year hiatus to bestride the political stage as an outspoken Labour Member of Parliament, she has hardly been off the boards. First, King Lear in London, then Albee’s Three Tall Women in New York (with Laurie Metcalf, Tonys for both of them). And now she’s Lear again, in a different production, running through July 7 – one that obliges her to battle hostile scenic and sonic elements like Shakespeare’s mad monarch raging against the storm.

Yes, Jackson plays the title character, but this is no Queen Lear. Sam Gold’s production is defiantly gender- and color-blind, in keeping with a doggedly disparate approach to the whole thing. It’s stuffed with invention, but is such a mish-mash of acting styles, directorial conceits and high-concept gestures that the debris littering the stage in the final scenes can be seen as a metaphor for the entire evening.

Miriam Buether’s set is another large cube, this one walled in beaten gold and carpeted in royal purple. It’s a present-day pleasure palace (Trumpian, if you like) where, as the play opens, a black-tie reception is in progress to the strains of a string quartet (more on that later).

Miriam Buether’s set is another large cube, this one walled in beaten gold and carpeted in royal purple. It’s a present-day pleasure palace (Trumpian, if you like) where, as the play opens, a black-tie reception is in progress to the strains of a string quartet (more on that later).

Jackson is the smallest person on the stage, diminutive and wizened but hardly frail. She radiates “authority,” as the king’s sturdy defender Kent later observes, and her face at moments bears a striking resemblance to Ian McKellen’s Lear. When the king rashly divides his realm between his two fawning daughters, Regan and Goneril, disinheriting his youngest, Cordelia, who refuses to flatter him, Jackson seethes with energy – proud, peremptory and quick to anger. That high-voltage trajectory, once begun, has nowhere to go except louder, and it’s not until late in the play, when Lear is finally at peace in the strange clarity of madness, that Jackson’s magnificent vocal range and detailed physicality really come into play.

Sam Gold is a magpie director, his style anachronistic and eclectic, but here, at least, with no coherent object or pattern. For instance, Regan’s brutal husband, the Duke of Cornwall, is played by a deaf actor (Russell Harvard) whose ASL-signed dialogue is spoken by a servant. I’m guessing the casting is not a metaphor of some kind, but a more or less random instance of diverse casting. (Equally random, indeed mistaken, is the kilt he wears, when it’s Goneril’s husband who’s even putatively Scottish, since his dukedom is the ancient Scots province of Albany.)

That string quartet, playing a typically repetitive original score by Philip Glass, fits nicely into the opening scene but soon becomes an ever-present soundtrack underscoring (or overbearing) much of the action. When Lear, maddened by his faithless daughters’ cruelties, flees into a vicious storm, the strings saw away in a frenzy that, together with thunderstrokes created by actors beating against the metallic wall, nearly drowns out the king’s railing.

That string quartet, playing a typically repetitive original score by Philip Glass, fits nicely into the opening scene but soon becomes an ever-present soundtrack underscoring (or overbearing) much of the action. When Lear, maddened by his faithless daughters’ cruelties, flees into a vicious storm, the strings saw away in a frenzy that, together with thunderstrokes created by actors beating against the metallic wall, nearly drowns out the king’s railing.

Jackson is joined onstage by another Brit, the marvelous Ruth Wilson, who doubles as Lear’s candid daughter Cordelia, cool and resolute, and his caustic Fool, a Chaplinesque music-hall Cockney. It’s an apt double act, as they are two frank sides of the same coin, both speaking truth to power, unafraid of telling Lear the facts, indeed, unable not to.

Jayne Houdyshell is a bustling, no-nonsense Duke of Gloucester, father of the faithful Edgar and the scheming Edmund. For me, the production finally struck home in the quiet, poignant scene between Gloucester and Lear, after the storm and before the tragic climax – two old friends, one blinded and the other mad, both of them grieving parents betrayed by their children.

The cast is also diverse in their approach to Shakespearean language, or for that matter, acting in general. There’s a stylistic spectrum, from Jackson’s grand gestures and classical modulations, through Pedro Pascal’s snide, jokey Edmund to Sean Carvajal’s hip-hop cadences as Edgar. In the sweet spot of this continuum stands Kent, in the person of John Douglas Thompson, who’s well known to audiences at Shakespeare & Company (he’ll play Coriolanus there this summer), comfortable in the sweep and swell of the verse, neither grand nor prosaic.

The cast is also diverse in their approach to Shakespearean language, or for that matter, acting in general. There’s a stylistic spectrum, from Jackson’s grand gestures and classical modulations, through Pedro Pascal’s snide, jokey Edmund to Sean Carvajal’s hip-hop cadences as Edgar. In the sweet spot of this continuum stands Kent, in the person of John Douglas Thompson, who’s well known to audiences at Shakespeare & Company (he’ll play Coriolanus there this summer), comfortable in the sweep and swell of the verse, neither grand nor prosaic.

In an interview prior to opening, Sam Gold previewed Jackson’s performance for us: “Glenda is going to do something very intense, very special, very big. She is going to go through something most people don’t go through. Glenda Jackson is going to endure this, and you are going to witness it.”

And we do. Watching this near-legendary player battling a visual, sonic and stylistic cacophony, my overwhelming feeling was that whatever is lost in her performance is due to being, like Lear himself, “more sinned against than sinning.”

Hillary and Clinton photos by Julieta Cervantes & Sara Krulwich

King Lear photos by Brigitte Lacombe

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com