It was a scene straight out of a paranoid thriller: 1961, a Paris airport, the KGB circling ever closer around a famous Russian, bent on closing the net around their prey. A waiting plane destined for Moscow. At the last moment, a dash for freedom — with the help of the head of French border control, a White Russian whose father had been sent to prison for criticizing Lenin. Slipping the Soviet net, the Russian would be smuggled to the headquarters of the French police before finally defecting to the West for good.

But what sounds like an old James Bond story was the true tale of Rudolf Nureyev, the world’s most famous male dancer (though one might argue that Baryshnikov, who himself defected in 1974, could now lay claim to the title). While dancing with the Kirov during a tour abroad to promote the idea of Soviet cultural superiority — it was only a few months earlier that Yuri Gagarin and his Vostok 1 spacecraft had given the Soviet Union bragging rights to manned space flight — Nureyev’s behavior (breaking curfews, visiting Paris’s gay bars) had ruffled feathers in Moscow. Word was sent down: bring him back and show him his place. But such was Nureyev’s talent that neither the Kirov nor the embassy in Paris wanted to enforce the order; while they battled it out with Moscow, the dancer made his nimble exit.

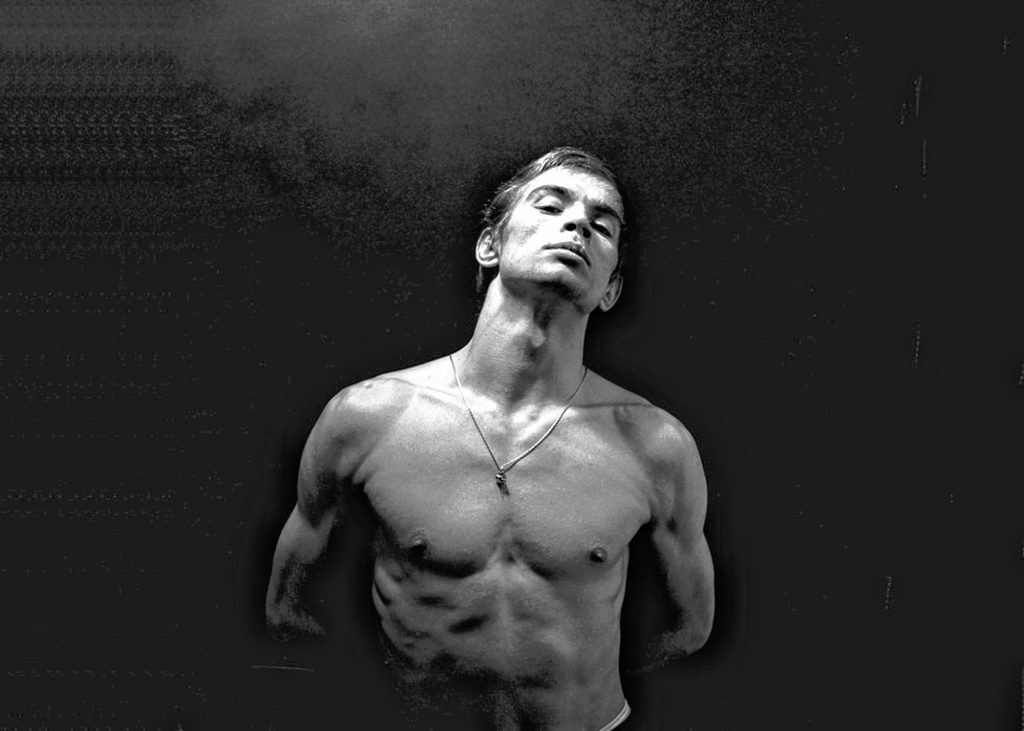

The airport escape is a dramatic highlight of Jacqui and David Morris’s new film Nureyev, which screens this Tuesday at Amherst Cinema. The documentary follows the dancer from humble beginnings — he was born on a Trans-Siberian train — through his rise in the competitive world of Soviet ballet, to his standing as a cultural icon. But the film also places Nureyev in the almost impossibly complex political world of his era, when the Cold War was an ever-present consideration for any international affair. In that context, the most famous son of Russia was practically the nation’s ideology made manifest — or so the leaders would have it. For Nureyev’s part, he makes pains to point out that he always considered himself a Tatar, rather than a Russian.

In retrospect, it sometimes seems that nothing could have held Nureyev back, and that allowing a wild 23-year-old loose in Paris might not be the best plan if you wanted him to return to Khrushchev’s regime. But it was a decision with costs; the young dancer would not be allowed to see his mother again until 1987, when she was dying. When Nureyev himself passed away just six years later of complications from AIDS, he was still without the family he always said he wanted to start someday.

And while the airport defection might be the defining moment of his life, it is still only a moment. The Morris’s film mixes the more famous footage of Nureyev’s public career with rare and early archival film shot during his performances in Russia, as well as some never-seen footage of him performing works from choreographers Martha Graham and Paul Taylor. There are also scenes of a modern dance troupe interspersed in the narrative, as a sort of dramatic retelling of pieces of Nureyev’s life (one wonders what the dancer himself — famously temperamental and famously sure of his own greatness — would make of someone else dancing his story).

With the Ralph Fiennes-directed Nureyev biopic The White Crow making the rounds, there is no better time to take in the Morris’s documentary. Dramas can do great things, but when your subject is supposed to be the best in the world at what they do, it always pays to be able to get a look at the real thing. See them both, and get a fuller picture of all that one man’s body contained.

Nureyev, June 4, 7 p.m., Amherst Cinema, 28 Amity St., Amherst

Jack Brown can be reached at cinemadope@gmail.com.