The best thing about summer theater in this region is its variety. Last weekend, for instance, I saw an Irish drama, an American musical and a world premiere.

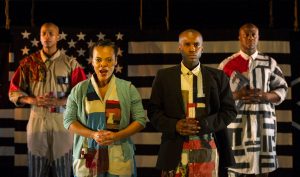

The premiere, at Barrington Stage Company, is a metaphor within a satire that becomes an indictment. America v. 2.1 is a play for the Fake News Era. It imagines this country in a “not-too-distant future” when black people have been expunged from the U.S. population and their history not erased, exactly, but turned inside out.

It takes place onstage and backstage at a kind of theme park where four actors are performing a pageant titled “The Sad Demise and Eventual Extinction of the American Negro,” which is also the subtitle of Stacey Rose’s play. We are in an Orwellian world where fiction is truth and black is, quite literally, white: The performers are black people performing a white distortion of black history.

It takes place onstage and backstage at a kind of theme park where four actors are performing a pageant titled “The Sad Demise and Eventual Extinction of the American Negro,” which is also the subtitle of Stacey Rose’s play. We are in an Orwellian world where fiction is truth and black is, quite literally, white: The performers are black people performing a white distortion of black history.

Their employers, represented by a disembodied voice on the backstage intercom, keep them in line with threats of violence. It’s a layered irony, a bitter echo of the world in which their ancestors were enslaved within a system that viewed their servitude as right and just.

The quartet is led by Donavan (Ansa Akyea), an older man rather wearily accepting his role as overseer. The others, underfed and overworked, are Jeffrey (Peterson Townsend), who had to abandon his son in order to take this job and now chafes under the yoke; Grant (Jordan Barrow), who sees a ghost from the past haunting the performance; and Leigh (Kalyne Coleman), a chipper self-help enthusiast whose enthusiasm wears thin.

The twisted tale they’re obliged to tell in this reboot of history is dedicated to “our Almighty Founding Fathers” and paints a portrait of “hard working White citizens and their cooperative Negro allies.” The picture gallery includes such hybrid heroes as Jesus Chris Lincoln (assassinated by Negroes) and Donald Reagan, along with renegade race traitors like Marcus Shabazz X and Baracka Saddam Osama, and concludes with the ultimate engine of the Negroes’ self-destruction, Hippity-Hop.

It’s a conceit at once ingenious and horrifying. The play moves in parallel arcs, alternating between the grotesque onstage pageant and a growing rebellion offstage, until the two collide.

It’s a conceit at once ingenious and horrifying. The play moves in parallel arcs, alternating between the grotesque onstage pageant and a growing rebellion offstage, until the two collide.

While I was impressed by Logan Vaughn’s vigorous production and the gifted performers’ commitment to the painful material, I found the 90-minute show a bit repetitive and heavy-handed, and the backstage dialogue impassioned but generic. Afterward, though, I found myself quite moved. The audience for this grisly minstrel show is, of course, the play’s audience, and its target is white America’s passive complicity in creating and sustaining this blood crime.

Subtle it’s not, but this is an important play to experience, reflect on, and most imperative, discuss. There are talkbacks after most performances.

After Happily Ever After

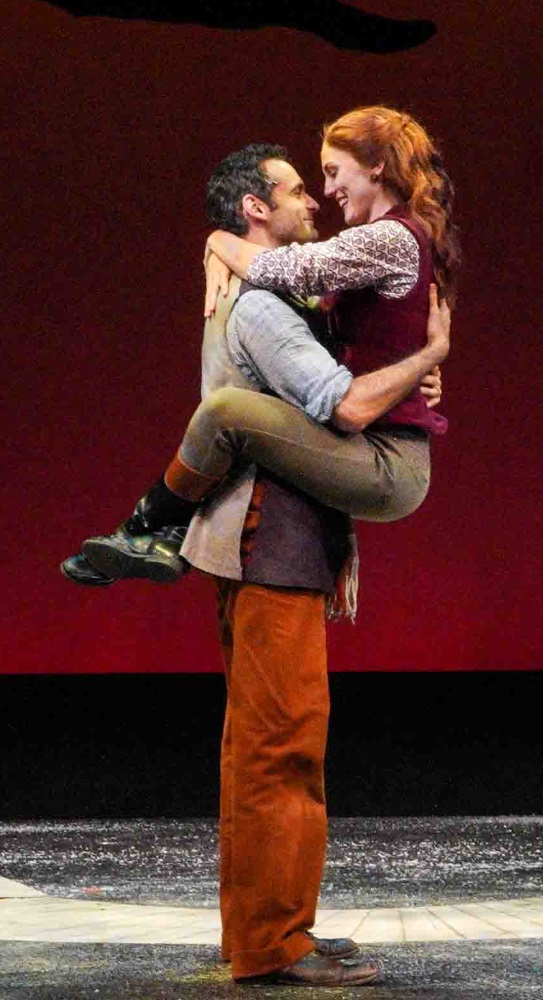

Into the Woods, also at Barrington Stage, is Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s fairytale mashup, the stories of Cinderella, Jack and the Beanstalk, Little Red Riding Hood and Rapunzel wrapped up in the fertility quest of a humble baker and his wife.

Director Joe Calarco and choreographer Mayte Natalio move the large cast nimbly around and through the life-size picture frames that comprise Brian Prather’s set, suggesting both storybook illustrations and a through-the-looking-glass world. Jen Caprio’s witty costumes range from the Wolf in black leather to Cinderella’s stepsisters in pink taffeta, with hair (by J. Jared Janas) to match. Brandon Hardy’s design for Jack’s cow Milky White — a fully articulated semi-abstract marionette — cleverly solves what’s usually a cumbersome prop.

Director Joe Calarco and choreographer Mayte Natalio move the large cast nimbly around and through the life-size picture frames that comprise Brian Prather’s set, suggesting both storybook illustrations and a through-the-looking-glass world. Jen Caprio’s witty costumes range from the Wolf in black leather to Cinderella’s stepsisters in pink taffeta, with hair (by J. Jared Janas) to match. Brandon Hardy’s design for Jack’s cow Milky White — a fully articulated semi-abstract marionette — cleverly solves what’s usually a cumbersome prop.

In the appealing and refreshingly multicultural cast of 15, I particularly enjoyed Jonathan Raviv and Mara Davi as the soft-hearted Baker and his practical wife, Dorcas Leung as a fearless, feisty Little Red, and most of all Mykal Kilgore as the ugly old witch who turns into a ravishing drag queen. Kilgore also possesses the most sensational voice in an ensemble of excellent singers.

The production is buoyant and inventive, but doesn’t quite solve the show’s nagging second-act problem. Just as the characters, after their fairytales come true, struggle to continue their stories on their own, so the script can’t top its intricate first-act tapestry. The follow-up dangers and complications aren’t as engaging, so the show feels quite as long as its 150-minute running time.

What’s Going On?

I should have known The Night Alive is a ghost story of sorts, as all of Conor McPherson’s plays at least flirt with the supernatural. I didn’t know this one, which opens Chester Theatre Company’s 30th season, so it didn’t really register until the play’s very last moment.

Tommy lives in a squalid room in his uncle Maurice’s Dublin house (you can almost smell Ed Check’s crowded set), subsisting on odd jobs with his affable, slow-thinking pal Doc. Their shambolic life is shaken up when Tommy rescues a young woman from a beating on the street and brings her home. He cleans her up and gives her shelter, and his protective instinct leads to a hesitant hope of romance. Turns out she’s a prostitute who’s been assaulted by her “boyfriend,” who turns out to be a suave psychopath.

Tommy lives in a squalid room in his uncle Maurice’s Dublin house (you can almost smell Ed Check’s crowded set), subsisting on odd jobs with his affable, slow-thinking pal Doc. Their shambolic life is shaken up when Tommy rescues a young woman from a beating on the street and brings her home. He cleans her up and gives her shelter, and his protective instinct leads to a hesitant hope of romance. Turns out she’s a prostitute who’s been assaulted by her “boyfriend,” who turns out to be a suave psychopath.

McPherson’s characters tend to live lives of garrulous desperation, haunted if not by actual phantoms then by memories, regrets and their own dogged hopelessness. His plays are filled with quotidian events and fueled by meandering but entertaining dialogue. The playwright has said he’s “always trying to wrong-foot the audience,” first putting us in a comfortable place “and then you suddenly up the stakes exponentially, and they’re like, Oh shit, I didn’t see this coming.” There are two sudden acts of violence in The Night Alive, and while they’re breathtaking, neither has a significant outcome, so they feel a bit gratuitous.

In the excellent cast, Justin Campbell gives Tommy a rough-hewn tenderness while Nick Ullett gives Uncle Maurice a shabby gentility. Marielle Young gives Aimee a determined toughness that doesn’t quite overcome her fresh-faced youth. Joel Ripka gives the sadistic boyfriend a slick street-wise sheen. And James Barry gives the show’s most engaging performance as the play’s most interesting character, Doc, gazing wide-eyed through big glasses with a kind of stunned enthusiasm.

In the excellent cast, Justin Campbell gives Tommy a rough-hewn tenderness while Nick Ullett gives Uncle Maurice a shabby gentility. Marielle Young gives Aimee a determined toughness that doesn’t quite overcome her fresh-faced youth. Joel Ripka gives the sadistic boyfriend a slick street-wise sheen. And James Barry gives the show’s most engaging performance as the play’s most interesting character, Doc, gazing wide-eyed through big glasses with a kind of stunned enthusiasm.

Daniel Elihu Kramer’s production is efficient and affecting, but I wish he had layered in more of McPherson’s creeping sense of an otherworldly reality, to help us absorb the sudden jolts and make sense of the script’s metaphysical hints at the nature of time, space and the afterlife.

In a spontaneous moment, Tommy, Doc and Aimee dance to Marvin Gaye’s anguished anthem “What’s Going On?” — a question that haunts this play. By startling coincidence, America v. 2.1 ends with the same song, challenging us with the question that haunts this country.

America v. 2.1 photos by Daniel Rader

Into the Woods photo by Stephen Sorokoff

The Night Alive photos by Andrew Greto

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com