When over the past several years states began to legalize marijuana for medicinal purposes and then some of them for recreational use, many people from the Baby Boomer generation witnessed something they doubted they would ever see in their lifetimes. People who had long known or believed that marijuana was a far safer and beneficial alternative to alcohol had that conviction sanctioned by some state governments. Marijuana advocates finally had their hard-earned victory.

Yet if one now gazes out at the cultural horizon, there is a storm heading our way the impact of which would not only dwarf cannabis legalization, it may have a transformative effect on the entirety of our social fabric. As vividly detailed in Michael Pollan’s 2018 bestseller How to Change Your Mind (Penguin Books), momentum is building towards the legalization and mainstreaming, at least for medical use, of the class of substances known as psychedelics or entheogens. Yes, LSD, psilocybin (found in certain mushroom species), and mescaline (from the peyote cactus) are undergoing a resurgence being described as a renaissance.

Unbeknownst to most people, research and clinical studies on psychedelics have been going on at universities and medical schools in the U.S. and Europe for much of the past two decades. Psilocybin has already been passed through Phase II clinical trials by the FDA, and if Phase III is successful it may be approved for psychiatric treatment early in the next decade. How psychedelics have returned from the abyss and reached this level of approval by the U.S. medical establishment is a story of how some scientists, believing that something of great value was lost when psychedelics were made illegal in the 1960s, made it a mission to regain and rehabilitate these substances for a new generation. But another surprising aspect of this renaissance is how this research has opened a window to the world of spirituality that most involved wouldn’t have thought possible.

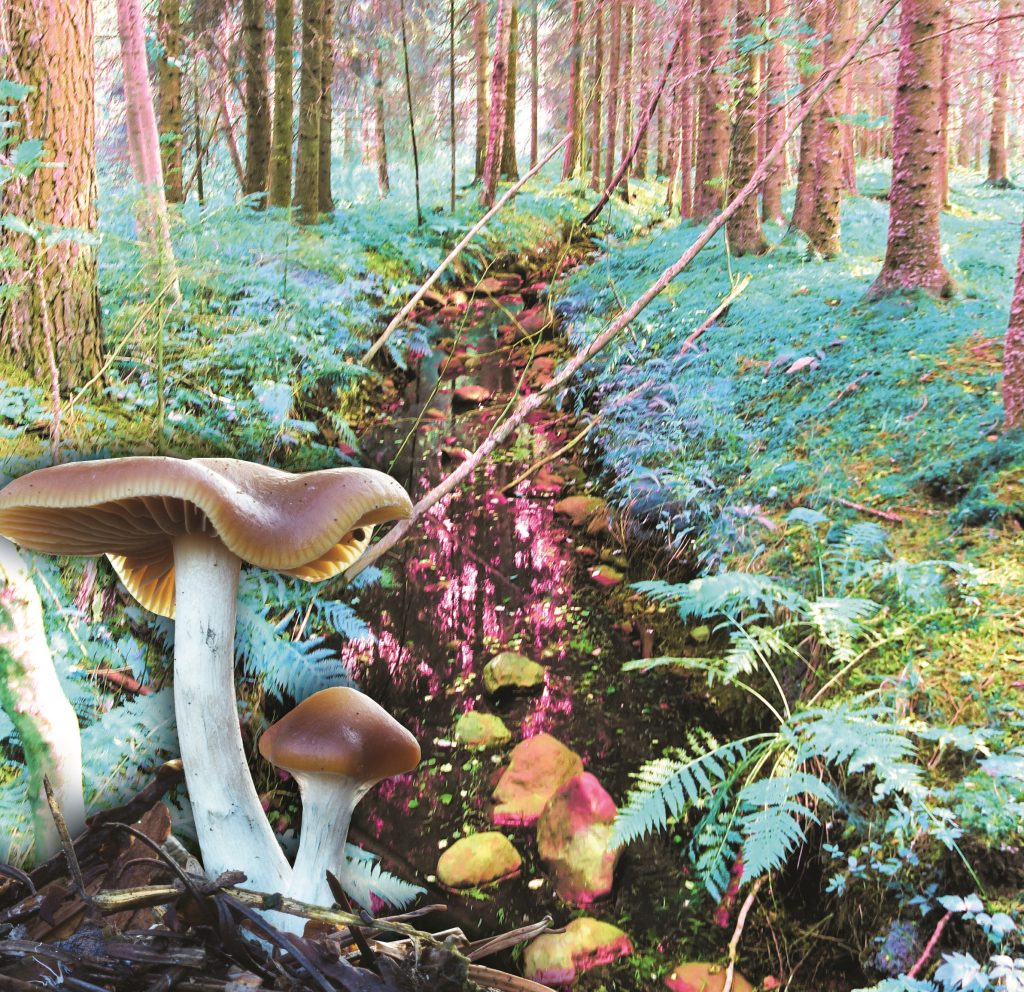

What makes psychedelics such a fascinating and important topic of interest is that their very existence, unlike anything else this writer can conceive of, has to be considered as being of deep philosophical significance. Here we have a naturally occurring molecule or chemical, that nature has placed in various plants and fungi, that users have insisted for centuries elevates their consciousness to an unmistakable level of spiritual awareness and realization. There is nothing else that allows for science and spirituality, those two supposedly irreconcilable realms of human endeavor, to be analyzed for their connectedness, not their distinctions and differences.

Legal status

Encouraging news for legalization advocates occurred earlier this year, when Oakland, California, and Denver, Colorado, passed measures to decriminalize the possession of psilocybin mushrooms. Campaigns to place mushroom decriminalization referendum questions on 2020 election ballots have also begun in Oregon and California. But while these events represent progress for those hoping for legal sanction for personal use, the scope of these efforts are likely to be limited in size at least until there is widespread approval for medical use, much like what happened with cannabis. In fact, if there is an area of disagreement among advocates it is the types of usage psychedelics should be legalized for.

Outright legalization for recreational use a la marijuana? While there are still those who hope for this level of social acceptance and government approval, the majority opinion is that might not be the best idea. While research has shown that psychedelics are remarkably safe, nontoxic, and completely nonaddictive, there is as with any substance the potential for misuse. They are not for drinking beer with and watching a Three Stooges marathon. Activists have a genuine reverence for psychedelics and don’t want to see them being used frivolously.

Applications for psychedelics for which there is much more enthusiasm are in the medical/psychiatric and spiritual/religious fields — the psychedelic movement has always been about more than just medical usage. The true believers from outside the medical profession have always envisioned broader applications for psychedelics, especially for their use in spiritual contexts. The phrase “the betterment of well people” is a mantra for those with this mindset. Activist Bob Jesse, founder of the Council on Spiritual Practices, would like to see trained and certified psychedelic guides administer entheogens (what psychedelics are more often called when describing their use in spiritual contexts) in contexts which to Pollan sounded “a lot like churches.” Others envision psychedelics being used in spa-like or religious retreat settings, again with trained guides present to take care of people having their experience and then helping them integrate it afterwards.

Before the 1960s there was no law restricting the use of entheogens and they have been in use for spiritual purposes by cultures around the world for centuries or millennia. In the Western Hemisphere evidence indicates widespread usage among indigenous cultures throughout the Americas, with usage in Latin and South America, and among Native Americans, continuing today.

Southern Oregon University Religious Studies Professor Martin W. Ball claimed that many of the world’s religious and spiritual traditions are rooted in ancient use of entheogens. In hunter-gatherer societies, the predominant form of spirituality was shamanism, and shamans have always made use of plants and fungi, including entheogens, that alter consciousness, he said.

“The ancient Greeks used entheogens in their religions. So too did ancient Hindus,” said Ball. “There’s evidence for entheogen use in ancient Egyptian religion, Zoroastrianism, indigenous African and Native American traditions, to name just a few. It’s important to understand that it was (and is) a global phenomenon and has not been limited to any particular time or place in the world.”

Unfortunately, those centuries of prior spiritual or sacramental use became problematic when the U.S. started making all known entheogenic agents illegal in the 1960s, but in 2006 a slight legal opening for spiritual use appeared courtesy of the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled that the UDV, a small religious sect founded in Brazil in 1961, could legally import ayahuasca, an entheogenic tea it uses as a sacrament, into the U.S. The Court based its decision on 1993’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which when enacted allowed the Native American Church to continue the peyote ceremonies that had been a part of the Church’s worship for decades. The UDV, which stands for Union of the Plants in English, expanded in the U.S. after the ruling, and had about 525 American members in nine church communities in 2018.

So, it seems as if a legal precedent has been established that sanctions entheogenic use in religious worship, but there are caveats. Part of the Court’s decision included the recognition of the UDV as an already existing religion, so it remains to be seen how the government would respond if an American citizen wanted to establish a new church in which entheogens were part of its practice or worship.

Science and spirit meet

Mark Hart of Deerfield was able to shed some light on why psychedelics have been used in spiritual practices or religious ceremonies for centuries. Hart has a psychotherapy practice in Amherst but also has a Ph.D. in theology from Boston College, so he is a person with a rare blend of psychological and religious knowledge and insight. In addition to his psychotherapy practice he is also a founder and leader of the Bodhisara Dharma Community in Amherst, which teaches insight meditation and other practices from the Buddhist tradition.

When asked about the spiritual experiences many people on entheogens report Hart said, “People report insights on reality that are not unlike those of people in profound meditative states. I used to be somewhat of a Buddhist chauvinist, saying our way of meditation is the best but I would say in the last 10 years that has gone by the wayside. My suspicion is that people do have genuine spiritual experiences on these substances. And I think the proof is in the lasting effects of these experiences.”

Martin Ball, the Oregon religious studies professor, has been an advocate for entheogenic spirituality for years and has written several books on the topic. “Not all use of psychedelics results in a spiritual or mystical experience, but these experiences do show up quite unexpectedly and regularly and can also be intentionally sought after through conscious use of entheogens. It’s very interesting that these kinds of experiences can happen whether one is seeking them out or not. In fact, one could make the argument that psychedelics and entheogens are the premier tool for having deep spiritual experiences simply because they are so reliably effective and potentially powerful.”

The questions statements like this raise are as profound as they are obvious. What are we to make of the mushrooms, cactus, and other botanical forms of life that have this amazing power to profoundly alter our state of mind and raise our awareness from the physical to the spiritual realm of being?

What we do know is that the power of psychedelics to create or enable these shifts in consciousness is not a recent discovery. And what may be more impressive to some people is that it was not yogis, gurus or other New Agers first making these claims, but the scientists who have been researching psychedelics from when LSD was first synthesized in 1938 and continuing to the present day. Almost all of those who led psychedelic research programs from the ‘50s onward sampled psychedelics for themselves, and even those who were staunch atheists or materialists before their experience felt as if profound truths about the existence of a spiritual realm were being revealed to them. Most if not all of the research up until the 1966 prohibition led many of the scientists involved to feel strongly about the potential of psychedelics as a possible agent for human transformation and societal betterment.

Even in the pre-1960s much of the focus of psychedelic research changed from psychiatric treatment of the mentally ill to something much more encompassing: bringing peace, happiness, and spiritual understanding to all of humanity.

If one person stands out as the leading figure in the psychedelic renaissance, it is Roland Griffiths, who heads a team that restarted psychedelic research at Johns Hopkins in 1999. In fact, Pollan writes that if there is a date that the revival fully blossomed it was 2006, and the key event triggering it was the publication in the medical journal Psychopharmacology of Griffiths’ paper “Psilocybin Can Occasion Mystical-Type Experiences Having Substantial and Sustained Personal Meaning and Spiritual Significance.” That the words “spiritual” and “mystical” could appear in a research paper’s title is remarkable enough, but even more so was the enthusiasm with which the paper was received by the scientific establishment. It was as if Griffiths had singlehandedly created a space allowing for the spiritual to be accepted as a subject of legitimate scientific inquiry.

The research: News from the clinic

Among the most recent and current psychedelic research programs is one at New York University. Here researchers are working to see if psychedelics can be helpful for people with very difficult to treat psychological conditions, most notably those who have been diagnosed with cancer and are facing a possible terminal prognosis. The NYU psilocybin cancer trial is trying to determine if psilocybin can help people facing the greatest personal crisis there is: the existential fear and dread that comes with knowing that you have only a short amount of time to live. And the results thus far have not only amazed researchers, they’ve shown how spirituality has been thrust into the scientific paradigm.

Stephen Ross, part of the NYU research team, saw things in his patients he could hardly believe and said, “People who had been palpably scared of death — they lost their fear. The fact that a drug given once could have such an effect for so long is an unprecedented finding. We have never had anything like that in the psychiatric field.”

One case study Pollan described is that of Patrick Mettes, a New York man with bile duct cancer who volunteered for the NYU program and had his initial psilocybin session in January 2011. Mr. Mettes was able to speak in great detail about his experience even as he was having it, at one point sitting up and saying to his doctors “Everyone deserves to have this experience, that if everyone did, no one could ever do harm to another again… wars would be impossible to wage.” He eventually added, “The sheer joy, the bliss, the nirvana, was indescribable. I know I’ve had no earthly pleasure that’s ever come close to this feeling. No sensation, no image of beauty, nothing during my time on earth has felt as pure and joyful and glorious as the height of this journey.”

Mettes lived another 17 months after his experience, and loved ones say he seemed to carry that bliss with him the entire time. From his hospital bed in his final days he was the one consoling his wife and friends, not the other way around. “It was like he was a yogi. He put out so much love,” his wife Lisa said.

One thing I was struck by upon reading these accounts is how similar they seem to those I’ve read of people having near-death experiences in the now abundant literature on that topic. This is probably not a coincidence or misjudgment. Johns Hopkins researcher Katherine MacLean said, “A high-dose psychedelic experience is death practice,” or almost like a dress rehearsal for dying. But people experience the blissful realization that there is something on the other side, so the spiritual implications of this are easy to see.

Psychedelics and the brain

While researchers in the U.S. have focused more on the subjective experience of psychedelics and its possible therapeutic applications, in the U.K. the focus has been on how they interact with the brain itself and its neurological functioning. At Imperial College in London, researcher Robin Carhart-Harris has discovered is that it is not the drug that the experience derives from. Instead, they are entirely the creation of the mind/brain.

Many people have heard by now the medical maxim that humans only use about 10% of their brain’s capacity. Modern brain imaging and scanning technologies used in neurological research have more or less confirmed this. But in addition to that, a 2001 discovery showed that most of that 10% is located in an area known as the default mode network, DMN for short. The DMN can be defined as the area in the brain where the concept of self and ego consciousness is constructed. And by the time a person reaches adulthood, the DMN’s neurotransmitter pathways become so worn in by overuse that directing brain activity outside of the DMN becomes almost impossible. Researchers liken it to a pathway that has been cleared through fallen snow that people habitually gravitate towards. That is what gives people the sense that they are trapped in captivity of their ego/self-identity. Psychic walls are built that confine the person’s subjective experience and create the impression that the self is forever a separate entity from the world perceived by the senses. And an overactive DMN is linked to numerous mental health problems, most notably anxiety, depression, and existential distress.

Returning to the snow analogy, what psychedelics do is add a fresh layer of snow to the brain and cover the DMN, allowing mental activity to take place along neurotransmitter connections the person has likely never used before. Another way it has been described is that psychedelics “reboot” a person’s neural activity into a state of consciousness where the usual distinctions between self and world, subject and object, dissolve. This further convinces those having the experience that consciousness continues after the self no longer exists, with the resulting effect being the perception that a transcendent spiritual realization has been achieved.

One more feature of the research that is of vital importance is how the brain scans of people having psychedelic experiences and those having mystical experiences through deep, advanced meditation are remarkably similar. Judson Brewer, now at the Center for Mindfulness at UMass Medical School in Worcester, has reported that scans show in both instances brain activity in the DMN is significantly reduced.

An interesting paradox is at work here. Research involving psychedelics has been applied with the highest standards of the scientific method, yet the success of this research seems to depend on the prevalence of mystical experiences that take subjects into places science is unable to venture. It may have been the great religious scholar and theologian Huston Smith who expressed the situation best. In a letter to Bob Jesse after the publication of Roland Griffith’s 2006 paper that got this Renaissance started, he wrote, “The Johns Hopkins experiment shows — proves — that under controlled experimental conditions, psilocybin can occasion genuine mystical experiences. It uses science, which modernity trusts, to undermine modernity’s secularism. In doing so it offers hope of nothing less than a re-sacralization of the natural and social world, a spiritual revival that is our best defense against not only soullessness, but against religious fanaticism. And it does so in the very teeth of the unscientific prejudices built into our current drug laws.”

What does it mean?

Science has taught us that all forms of life evolve and adapt over the course of eons, and that they naturally develop attributes to better ensure their long-term survival. But what would be the reason that certain plant species developed psilocybin and mescaline over the course of their evolution? Botanical research has shown psilocybin and mescaline provide little if any benefit to their host organisms, but they do astounding things for the people who use them. It’s not a defense mechanism or something to strengthen an organism’s long-term survival prospects if it makes it more likely that humans will want to consume it.

Something is going on here. A person doesn’t have to be anti-science to believe that organisms that contain these incredible properties to enlighten minds to the spiritual realm of being couldn’t possibly have evolved on this planet by accident. Is the natural world we share this planet with trying to share secrets with us about life that it’s known all along? Is the immanent and transcendent God, in which we live and breathe and share our being, trying to speak to us through these amazing plants?

Most importantly, are we listening?

One of the things I loved about Michael Pollan’s book were its numerous references to something very dear to me and that is William James’ masterpiece The Varieties of Religious Experience, which is still thought to be one of the greatest nonfiction books of the 20th century even though it was published in 1902. James’ study of mysticism led him to believe that our everyday waking consciousness “is but one special type of consciousness, whilst all about it, there lie potential forms of consciousness entirely different. No account of the universe in its totality can be final which leaves these other forms of consciousness quite disregarded.”

Amen.

Peter Stilla is an editor at the Daily Hampshire Gazette and an ordained Christian Universalist minister. He lives in Deerfield with his wife and two daughters. Reach him at pstilla@gazettenet.com.