Time travel has been a perennial theme for fiction writers for over 200 years, as well as a theme from ancient myths, dating back far longer, from countries all over the world. It’s also an idea — or at least the notion of moving into the future is — that’s been examined by physicists through the study of the theory of relativity and phenomena such as black holes.

But short of building yourself a time machine, as H.G. Wells did in his 1895 novel of that name, time travel might best be achieved by immersing yourself in an historical novel — a tradition that also dates back centuries.

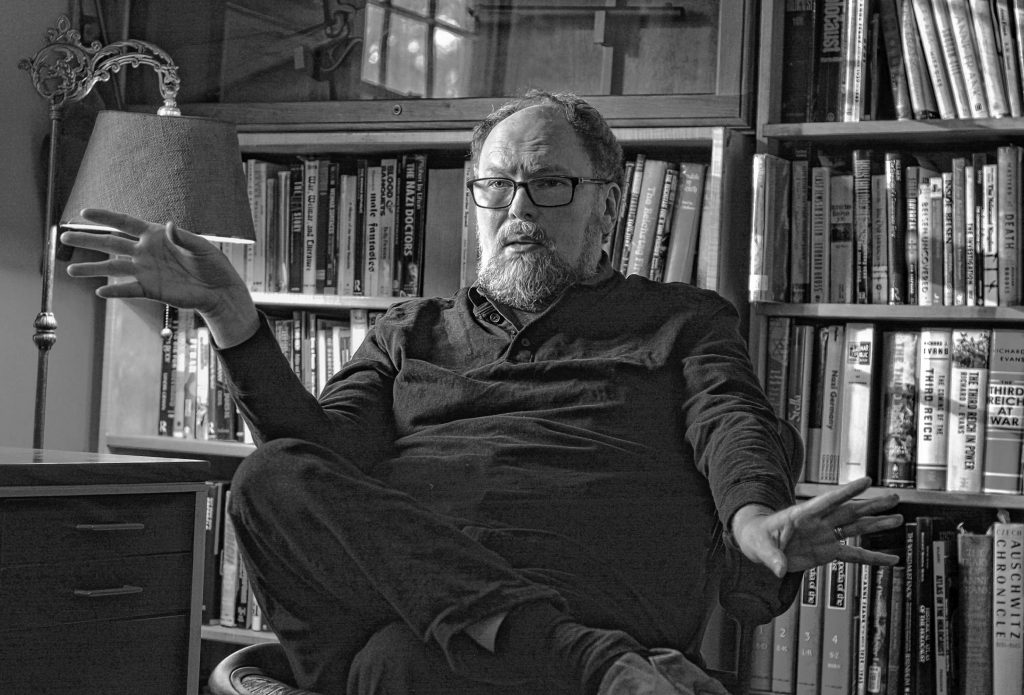

Amherst writer David Gillham has drawn on his study of World War II and the Holocaust in two novels set in WWII-era Europe. Jerrey Roberts photo

Why write about the past? That’s easy, says David Gillham, an Amherst author who’s written two novels set during the World War II era. “For me, I like the distance [the past] affords me,” he says. “I like to try to recreate those worlds with my own ideas and imagine how people interacted, how life might have felt and sounded.

“I try to bring the past forward as another way of understanding it,” adds Gillham, whose most recent novel, Annelies, imagines that Anne Frank, the famous teenage Dutch-German diarist of life in Nazi-occupied Holland, survives the Holocaust and struggles to put her life back together after returning to Amsterdam.

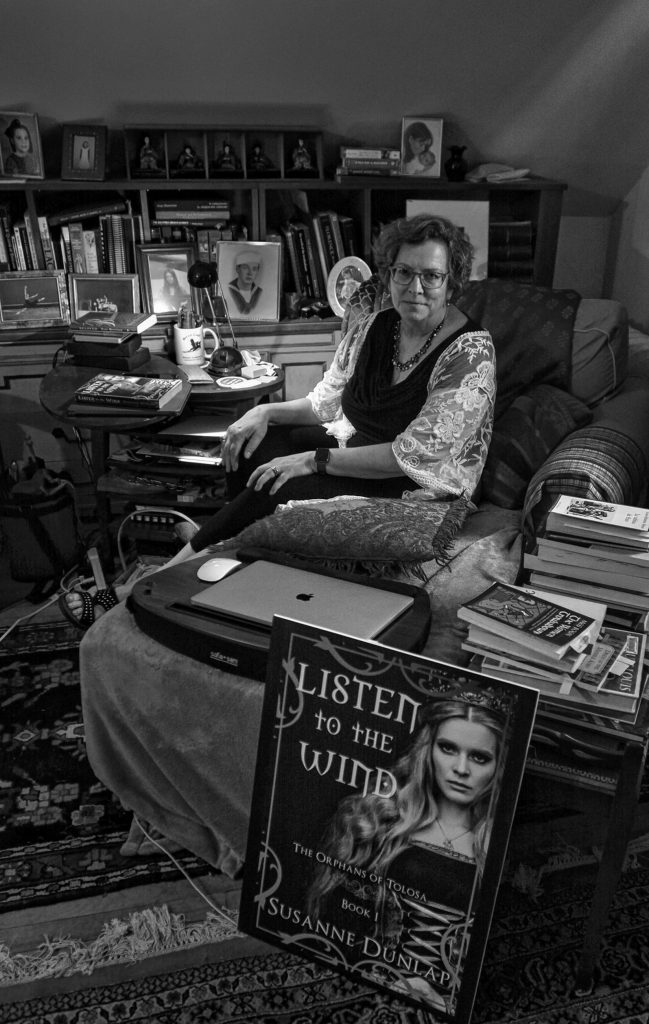

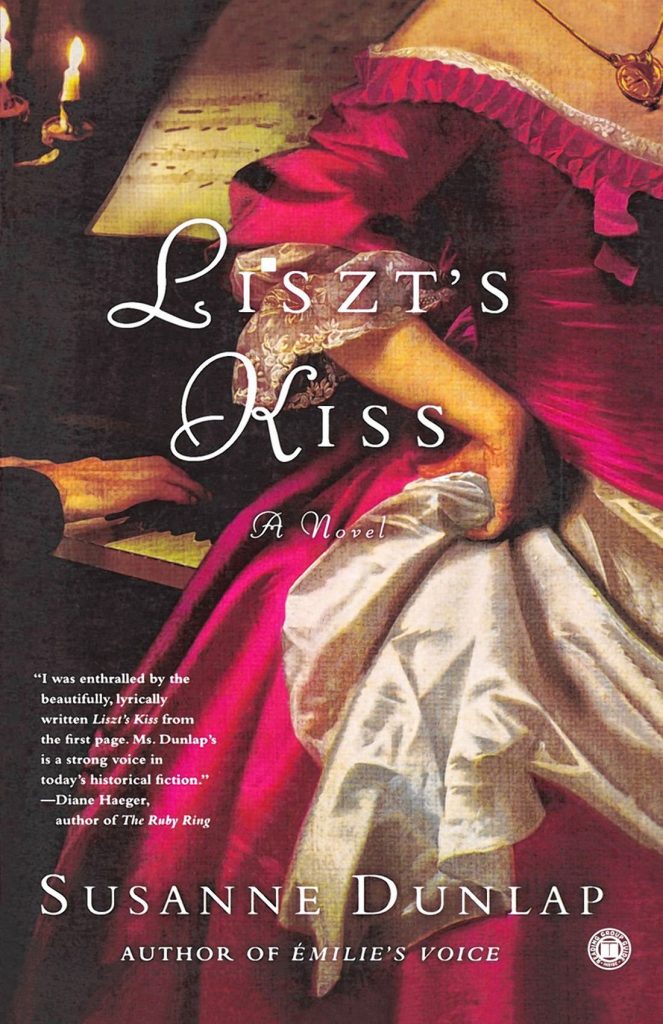

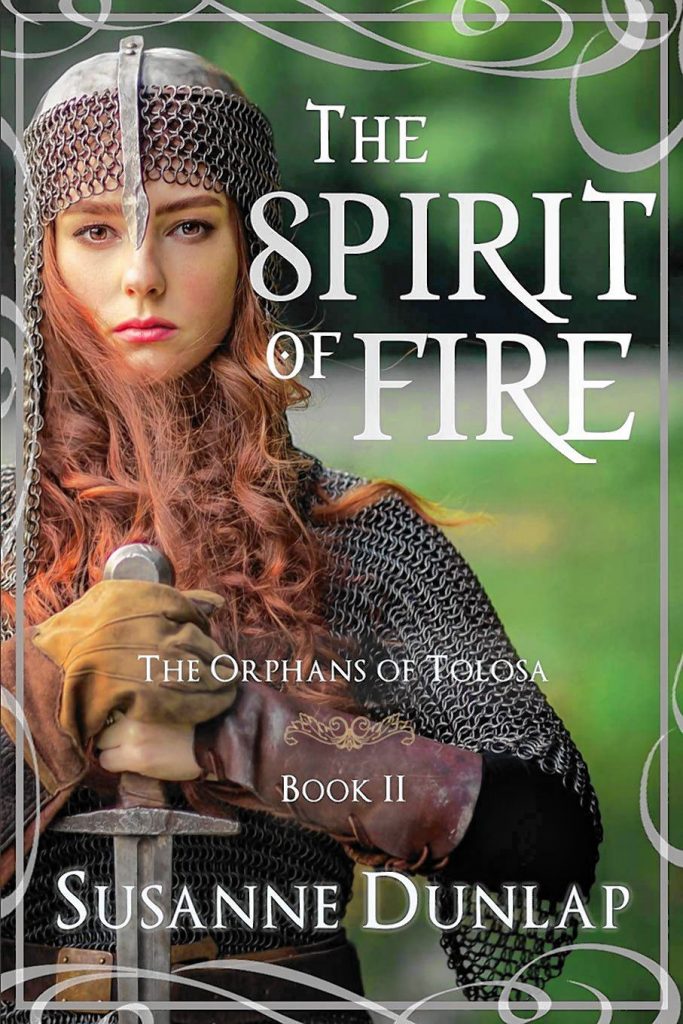

For Susanne Dunlap, the author of several young adult and adult novels whose settings range from medieval France to early 20th-century Russia, the entrée to historical fiction came in part after she earned a doctorate in music history but couldn’t find a suitable teaching post. With a background that also included promotional writing and music performance (as a pianist), Dunlap, of Northampton, decided to turn to historical fiction, in a series of books that frequently have music as an important theme.

Northampton author Susanne Dunlap has drawn on her background in music history and performance in writing a number of her historical novels. Jerrey Roberts photo

And Dunlap had another motivation with her fiction: making girls or young women the focus of her narratives. “So much of history is told from the perspective of men,” she says. Doing research on a particular era and then building a storyline around her female characters “is a lot of fun, and it’s a way to tell the stories of women, since we rarely hear about them.”

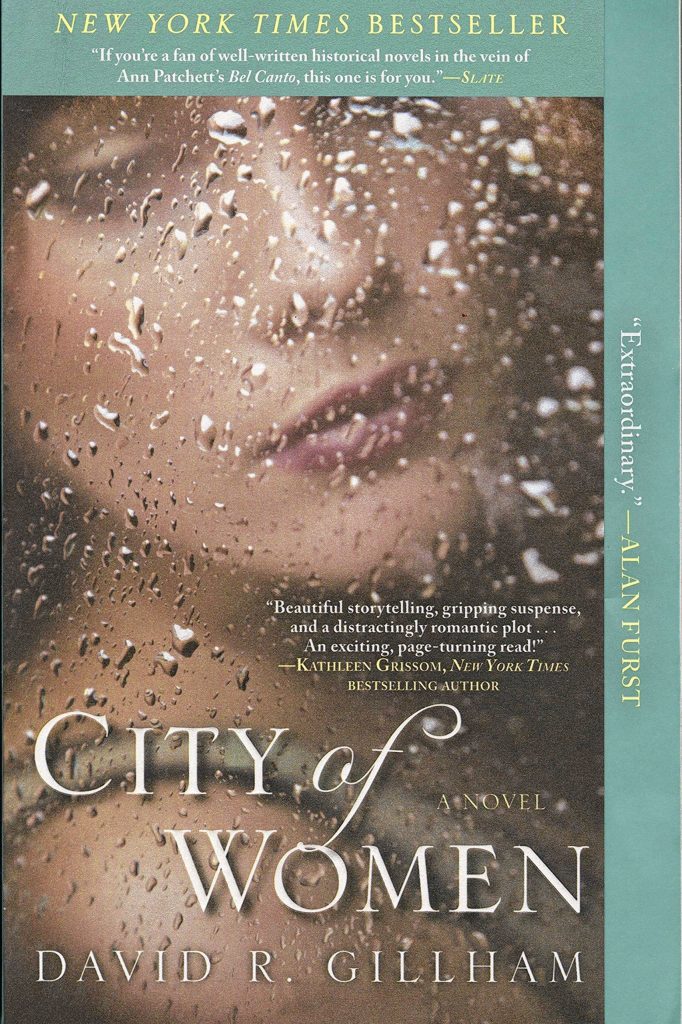

Along similar lines, Serena Burdick, of Greenfield, and Gita Trelease, of Deerfield, have centered their novels around young women in the past. Burdick’s first novel, Girl in the Afternoon, follows a young woman artist in 1870s Paris trying to make her way in the male-dominated world of Impressionism. Her newest, The Girls With No Names, to be published in January, is centered on two teenage girls, from very different backgrounds, who end up in a brutal “reform” institution for “wayward young women” in early 20th-century New York City.

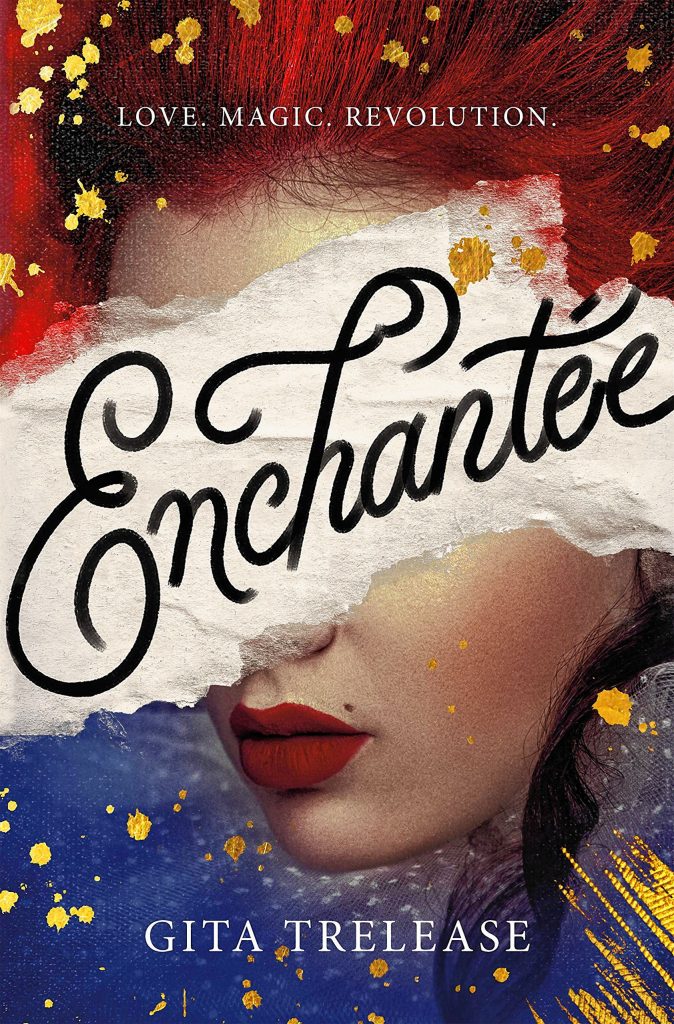

The protagonist of Trelease’s YA novel, Enchantée, meantime, is a poor teenage girl, Camille, who’s been orphaned in revolutionary-era Paris and must use her inherited gift of magic to fend for herself and her younger, chronically ill sister, Sophie. Camille takes on the dangerous gambit of disguising herself as a widowed baroness and gambling with the arrogant aristocrats who hold court at Versailles with King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

Trelease says she’s long been interested in history. Even as a young girl, she adds, she can remember visiting historical sites such as Plimoth Plantation or old houses and feeling “I could just go around the corner and I could be there, in the past…. It never felt like something that was that far away or distant.”

Later, after reading J.R.R. Tolkien’s fantasy The Lord of the Rings and then 19th-century English novelists such as Jane Austen and Charles Dickens, she was also struck by the similarities between the books. “In my mind, there’s not that much difference between Tolkien’s world and the country life of Jane Austen. They’re equally fantastical and enchanting.”

Facts and fiction

That said, writing believable historical fiction requires a good understanding of the era you’re writing about: the culture, the language, the smells and sights of everyday life, the way people acted and thought. Invoking real-life historical figures demands an even greater depth of research, enough to allow you to create imaginary scenes for that character that would not feel out of bounds to, say, a biographer.

Greenfield novelist Serena Burdick has written one story set in France in the 1870s and the other set in early 20th-century New York City.

The four Valley writers all say research is obviously a key part of their work, one they deeply enjoy. But they also face a challenge in employing that research judiciously, using it as a backdrop to the more important task of creating an immersive story.

“You try to extrapolate,” said Dunlap. “You want to understand what clothing looked like, how sanitation was handled, things that made up day-to-day life, and you build that in to serve the story … you’re not writing a history book.”

Dunlap says she doesn’t have her characters speak in some stylized, “old-fashioned” way, particularly when writing for younger readers. What’s more important is guarding against anachronisms: allowing modern terms and actions to creep into a narrative set in the past. When writing one of her newest books, The Mozart Conspiracy, set in Vienna in the late 18th century, she realized at one point she’d made a reference to “ ‘the weekend,’ and that obviously wasn’t right. That’s a 20th-century term. There wasn’t any concept of it at that time.”

What exactly do you draw on for research? Serena Burdick jokes that she doesn’t really consider herself an historical novelist, even given the subject matter of her first two books. But she became interested in the subject of Girl in the Afternoon because of her interest in Impressionism — in particular, the way women artists were shut out of many of the salons and art studios in Paris during that era. From reading about Berthe Morisot, one of the few female artists who won wide acceptance in male Impressionist circles, she began to build her own novel. She also immersed herself in French literature from that period, such as the novels of Émile Zola, to get a feel for the era.

“And for The Girls With No Names, I read [fiction by] Edith Wharton and about the Suffragette movement,” Burdick notes. “That was a really interesting time, when you had the end of the Victorian era and older women kind of clashing with the younger generation that was demanding changes.”

Deerfield author Gita Trelease says she wants her historical fiction to offer both an absorbing picture of the past and a narrative that has relevance to today’s world.

Gillham, the Amherst writer, says he brought his interest and extensive reading on World War II, the Holocaust and pre-war Europe to bear in his books. For his first novel, City of Women, set in war-time Germany, he relied on books he’d read of Berlin in the 1920s and 1930s as well as accounts of day-to-day life in the Third Reich (the story is a fast-paced literary thriller about a Berlin housewife who begins to help Jews hiding from the Gestapo as the tide of war turns against the Nazis).

For Annelies, Gillham did a close re-reading of Anne Frank’s full, unedited diary, read numerous books about her and her family and interviews with people who had known her, and visited Amsterdam and two Nazi concentration camps where the family was sent in 1944 after police found their Amsterdam hideout. He also plumbed the memoirs of Holocaust survivors.

“I try to hit a middle ground” between historical detail and narrative, says Gillham. “You can build in some of that detail in unobtrusive ways by, say, having a character take a train trip and look out the window … you want to be careful about giving history lessons and present [the history] in a way that enriches the story and doesn’t sidetrack it.”

Trelease says she turned to a number of sources for writing Enchantée, including biographies of Marie Antoinette and Lady Georgiana Spencer, a leading British aristocrat of that era who was a friend of the French queen and also led a notorious nightlife full of gambling, drinking and various love affairs. She relied as well on some primary documents and selected histories of the French Revolution. (Trelease lived in Paris and taught English for a few years after college and always thought the City of Light would make for a great setting for one of her novels.)

In addition, Trelease says she aimed in Enchantée (and in a sequel she’s now working on, Liberté), to draw links between the past and the future so that her narrative has the romantic appeal of a very different world but also feels “very close and true.”

In Enchantée, for instance, the gross inequality in revolutionary-era France “has some parallels with the inequality we see in our country and the world today,” she says, while Liberté examines the way “rumor, suspicion and fear came to dominate the French Revolution,” just as we see some people today refusing to trust media reports (“Fake news!”) and giving credence to internet-based conspiracy theories, Trelease adds.

Burdick notes that The Girls With No Names owes its origins to a more contemporary story: the horrific reports that surfaced in Ireland in the late 1990s of the Magdalene Laundries, “reform” institutions run by Roman Catholic orders for “fallen women.” As many as 30,000 girls and young women, according to various reports, were confined in prison-like conditions in these facilities in the 19th and 20th centuries, and 155 female corpses were uncovered in 1993 on the grounds of one site, prompting a huge outcry in Ireland.

Burdick at first thought about crafting a novel based on these reports but decided it was too recent a story. But doing further research on the subject, she says, led her to the system of “Houses of Mercy” in the U.S. in the 19th and early 20th centuries: religious institutions that claimed to want to improve the moral character of women but in reality reduced them to slave laborers, doing unpaid work such as washing clothes. One, located in upper Manhattan, became the focus of her novel.

“In that way you see the past catching up with the present,” says Burdick.

What they’re reading themselves

The four Valley novelists don’t confine themselves to the past. All mention reading contemporary fiction, and Trelease, who previously taught fiction and fantasy writing in college and high school, also has written poetry. For her part, Burdick is working on a new novel set in more recent times, one based on the life of Estelita Rodriguez, a Cuban-born Hollywood actress who starred in many westerns in the 1940s and 1950s.

Background material that Amherst writer David Gillham compiled for “Annelies,” his speculative novel about Anne Frank.

But they also mention a number of favorite historical novelists and titles of their own, such as Tracy Chevalier (Girl with a Pearl Earring) and Paula McClain (The Paris Wife). Gillham likes The Good German, a noirish story set in post-WWII Berlin by Joseph Kannon, and Trelease is partial to the work of Hilary Mantel, the English novelist whose two books about Thomas Cromwell’s rise to power under Henry VIII, Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, became international bestsellers.

Trelease points to Mantel as a good spokesperson for the value of the historical novel, both as a creative means for telling a story and for shedding fresh light on the past, especially for people who might be averse to reading straight history. That’s one of the appeals of writing about the past, adds Dunlap: It’s very simply “a lot of fun and a challenge as a writer to transport yourself to a different time, and hopefully bring readers with you.”

Given the widespread critical acclaim her Cromwell novels have garnered — both won the Booker Prize, Britain’s top literary award — there’s also a sense that Mantel has elevated the whole genre in the last decade or so. In an interview earlier this year with BBC History Magazine, Mantel said historical fiction used to be “conflated with ‘historical romance’ and looked down on as cheap escapism” even though “War and Peace is a historical novel, and no one ever suggested it was trivial.”

But today, Mantel added, historical fiction has gained greater acceptance because it “makes us turn our attention to the 99.9 percent of human activity that never made it onto the record — and which can only be recovered by the imagination. It can offer insight and new ways of thinking about some of the puzzles the past represents. It can also send readers to history texts, whetting their appetite to know more.”

As Trelease puts it with a laugh, “Some readers [of Enchantée] have said to me, ‘If this had been one of the ways I could have learned about the French Revolution in school, I would have been more attentive in class.’”

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@valleyadvocate.com.