In 1981, Ota Shogo had a vision: “A broken faucet center stage. A thin line of water from the spout. The sound of water. A variety of people come by, approach, touch the water, and pass on. In this composition, silence breathes as living human time, not as form.”

From these images came The Water Station (Mizu no eki), devised by the Sino-Japanese director with the actors of his Tokyo-based company, Tenkei Gekijo, or Transformation Theater. Now the Indian-born director Vishnupad Barve is giving it a rare staging in this country. It opens next weekend at UMass.

Before a rehearsal last week, he told me he came to this work because “I was trying to figure out how to bring in a dramaturgy which is not about representing someone in a direct way, and how to tell stories from the Asian theater, which is about ‘art-making,’ a play as a piece of art.”

In addition, he said, he “wanted to do theater which invites the audience to create their own stories while watching the piece, and to explore my understanding of physical action. The Water Station is perfect for that.”

That is, it’s a non-story told entirely without words and performed at a measured pace, in which certain actions and connections occur, without overt explanation, inviting each audience member to apply meaning to it – their own art-making – or to simply take it in.

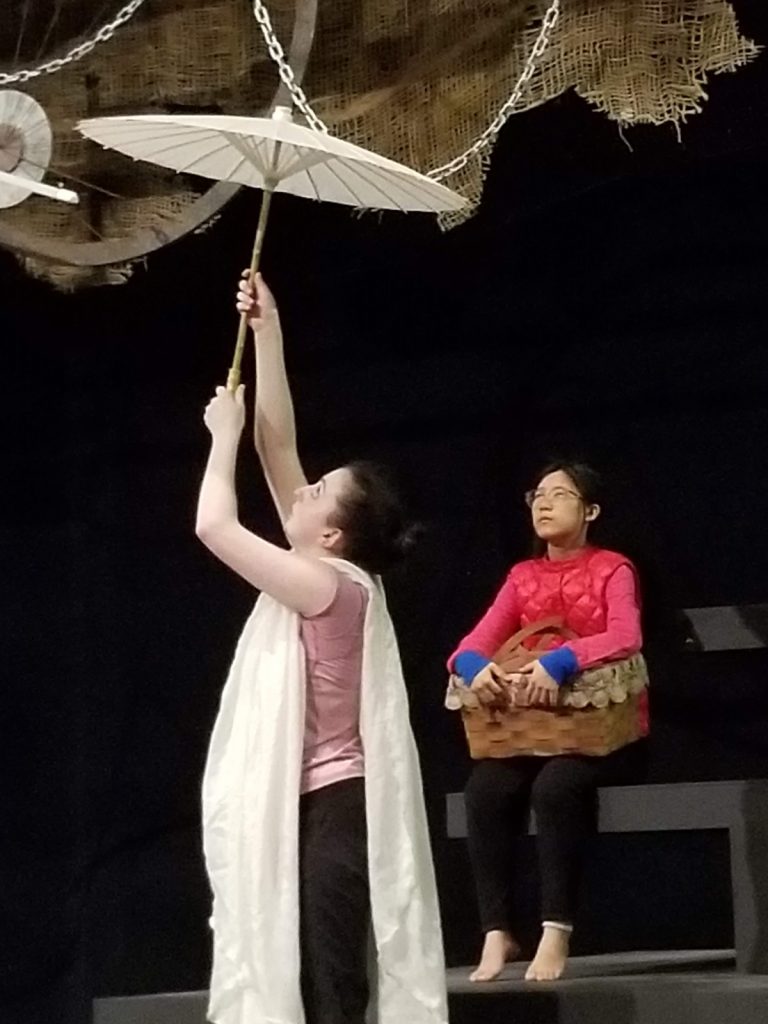

The basic structure is simple: Travelers, individually and in groups, laden with various possessions, arrive at a desolate resting place with a slow-running faucet backed by a towering pile of debris on which a lone figure sits, observing the action below. The voyagers drink and wash and interact – or not – and move on. Their movements are natural but slowed down – not slow-mo but deliberate, almost trancelike, punctuated with sudden bursts of motion.

The basic structure is simple: Travelers, individually and in groups, laden with various possessions, arrive at a desolate resting place with a slow-running faucet backed by a towering pile of debris on which a lone figure sits, observing the action below. The voyagers drink and wash and interact – or not – and move on. Their movements are natural but slowed down – not slow-mo but deliberate, almost trancelike, punctuated with sudden bursts of motion.

The script itself is a meticulous documentation of Shogo’s production, with every movement detailed, down to specific gestures. It’s quite the opposite of standard scripts, which provide the actors’ dialogue and basic blocking, and thus is closer to choreographic notation in dance. Within this framework, Barve said, the 80-minute performance becomes “all about the physicality. We clear the platform so the actors can build their own psychological platforms, their own stories,” and drawing on those stage pictures, so can the audience.

The stage, indeed, is little more than a long platform with a ramp descending to the fountain. Over the course of the performance, an abstract hanging sculpture descends above the stage one section at a time. While there’s no dialogue, there is sound – not only the constant trickle of the water, but music, running through the piece like a flowing stream. Erik Satie’s haunting Three Gymnopedies and a keyboard arrangement of an Albinoni oboe concerto are played live by pianist Amanda Huesmann.

The procession of weary travelers, encountered at one stage of a long journey, inevitably evokes thoughts of immigrants and refugees. But in a larger sense, Barve says, it’s all about “the process of life – travelers seen between two unseens,” like the vision of earthly existence in Hindu cosmology. “We are living life between two unseens. We are coming from somewhere and we go somewhere,” both of them unknown.

Like the play itself, the production process has broken with typical theater practice. Auditioners for the 16-member cast were asked to perform not monologues but short movement pieces. “We looked for specificity of gesture, and for stamina,” dramaturg Tatiana Godfrey told me. The latter is important because the slow, controlled movement asks a lot of the body.

Like the play itself, the production process has broken with typical theater practice. Auditioners for the 16-member cast were asked to perform not monologues but short movement pieces. “We looked for specificity of gesture, and for stamina,” dramaturg Tatiana Godfrey told me. The latter is important because the slow, controlled movement asks a lot of the body.

Every rehearsal includes training in the rigorous physical stagecraft of the Japanese auteur Tadashi Suzuki, led by UMass professor Milan Dragicevich, and yoga exercises to develop breath control, body awareness and “how to be present here and now,” as Barve put it. The actual scene work, he said, is an extension of those exercises, putting the physical forms and inner focus onstage.

Godfrey told me that one of a dramaturg’s jobs is to write an explanatory program note – in this case, “to teach the audience how to watch the show. It’s not what people are used to – not a dance piece, very much a play, but it’s not what they expect of a play.”

She compares it to looking at an abstract painting. “It’s just shapes and colors, but people can have very emotional reactions to it, and take away very different things from it. The same can be applied to our piece. You’re looking at a person moving through space, they stop at the water station, you’re hearing music, you put all these elements together and take something away from it.”

Feb. 27-March 7, Rand Theater, UMass. $15, $5 students/seniors. Tickets online or 800-999-UMAS.

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com