Editor’s note: Due to the dangers facing those seeking asylum and their families in their home countries, as well as the sensitive nature of their legal cases, the Advocate is using pseudonyms Ramon and Santiago for two asylum seekers featured in this story and refraining from naming their countries of origin.

Santiago left his home in the middle of the night to escape an authoritarian government in Central America, which to this day wants to capture or kill him.

Facing similar dangers, Ramon fled a civil war tearing apart his home country in West Africa.

“The government compiled a list of people that could not leave the country,” Santiago, who does not speak English, said in Spanish. “They wanted to sequester people and bring them to prison or to assassinate them. On one of those lists, I was included.”

These two now reside in western Massachusetts and are in different stages of the asylum-seeking process in the United States. Seeking asylum takes months and often years, and in the majority of recent cases results in a denial. An immigration judge granted Ramon with asylum status in June 2019 and Santiago is still working through the legal system with his next immigration court date in spring 2021.

They are two individuals among tens of thousands who fled their countries for fear of their lives and arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in recent years seeking the protected status of asylum in the United States.

In December 2018 and January 2019, these two men from very different corners of the world arrived at the Tijuana-San Diego border because they were no longer safe in their home countries — the two faced different situations, but both were persecuted by their countries’ governments. Their arrival coincided with the height of the so-called migrant caravan that originated in Honduras, which swelled to 4,000 to 7,000 migrants, as estimated by the United Nations.

‘No Turning Back’

Months before arriving at the Mexico-U.S. border, Ramon left his family living in a West African village after his country’s military killed his brother and burned down his home. Returning one day from work, he found the aftermath of the military’s attack and his mother told him to leave the country because it was not safe for him to stay.

In his country, which the Advocate is declining to name due to safety concerns for Ramon, there is a civil war between a separatist faction and the government, and the conflict has escalated to the point where Ramon says the government is arbitrarily attacking people who they perceive to be part of the separatists’ faction. Ramon and his family became targets, he said.

“I wasn’t home and they came looking for me,” he said. “So I had to run. I went to a neighboring village and tried to find out how things were going back home. And my mom said they were still looking for me. From there, I had to look for money and I went to a neighboring country.”

Ramon traveled through two African countries before getting on a plane in October 2018 to fly to Ecuador. He spent the next two months journeying through Central America and Mexico, sometimes through the jungle, sometimes through cities. He speaks no Spanish and often had to rely on Google translate on his cell phone to translate from English to Spanish so he could communicate. He would occasionally be wired money from his family to afford bus tickets and meals.

“The main thing on my mind was to get to safety,” Ramon said. “I wasn’t actually thinking straight because I was going through all the trauma and the stress of my brother being dead and my family not being safe at all. I was just like, ‘OK, let me go. If I survive, I survive, and if I don’t, then it’s OK. But it’s better to die trying than to just stay.’ That was what was on my mind, just trying to be safe.”

From Ecuador, Ramon crossed Columbia by bus and then entered Panama by boat. He traveled with a group of 30 into Panama, which included Indians, Bangladeshis, Chinese, and Haitians. They were smuggled into Panama overnight, and when they landed there, they were guided into the jungle. As agreed upon with their guides, they were left on a path in the jungle after a few hours. The group would make the rest of their way on their own.

Ramon, a man from West Africa, who has received asylum status dribbles a soccer ball, Monday, Feb. 3, 2020.

Some split off and traveled faster. Others were slower and could not keep up. Ramon encountered dead bodies along the route, some who had drowned in rivers, others laying in bushes. The group slept on the jungle floor at night. “We had no choice,” Ramon said.

“From the Panama jungle, it came to a point where we met the Panama army,” he said. “They kept us in a camp for four days and they put us in a boat and took us closer to Panama City. We spent another two days in a camp and then they brought us to Costa Rica immigration.”

The Costa Rican government gave him a pass for seven days so he could travel into Nicaragua, where he scaled a fence to enter its borders. He gave money to Nicaraguan authorities to get into the next country, Honduras, where he spent 11 days waiting for the government to allow him to continue north. By bus, he continued through Guatemala to arrive in the southern part of Mexico, where he stayed for a week in an immigration camp. After 15 days, he got on a bus bound for Tijuana.

“I wasn’t 100 percent safe,” Ramon said. “I was just barely safe because it was very risky. Especially going through Panama and all those countries. I was kind of lucky because most of the people get robbed along the way and some people died … I just knew there was no turning back.”

Ramon survived much during his journey to get to the U.S. border, but his challenges were far from over.

Seeking asylum in the U.S.

Asylum seekers typically leave their countries due to violence from drug cartels, hostile governments, civil wars, domestic violence, or persecution for belonging to a social group, which could include a racial or religious minority or a political affiliation.

During their stays in Tijuana, Mexico, Ramon and Santiago forged connections with Valley activists who were there to inform immigrants on how to get asylum status. Gaining asylum is a process that involves uncertainty at every step of the way: arriving at a U.S. port of entry, months of detention in a network of facilities across the United States, and potentially a years-long process in immigration court. It’s all undertaken in the hope that a federal immigration judge will grant them asylum status and residency in the United States.

Asylum status in the United States is similar to refugee status in that it may be granted for individuals who have been persecuted or fear they will be persecuted on account of race, religion, nationality, and/or membership in a particular social group or political opinion, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

The key difference is asylum seekers are already in the U.S. or are seeking admission at a port of entry; individuals can only seek refugee status from outside of the U.S.

During President Trump’s first week in office, he signed an executive order to broaden the ability of immigration agents to apprehend and deport individuals from the United States. Prior to the order, U.S. Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) would release asylum seekers and assign them dates to show up to immigration hearings if they did not pose a danger to a community; many of them were tracked with ankle monitors or other monitoring systems.

Now the process for seeking asylum has become a maze of draconian bureaucracy. It forces many asylum seekers who arrive at a port of entry at the U.S.-Mexico border to wait in Mexico before being admitted to begin their asylum claim process — a metering system that began in April 2018.

During January 2019, the administration instituted a policy called Migrant Protection Protocol, also known as Remain in Mexico, which forces asylum seekers to undertake their cases while in Mexico. Last month, a federal appeals court found Remain in Mexico to be legally invalid, stating that the policy is causing “extreme and irreversible harm,” and the Trump administration is expected to ask the Supreme Court to weigh in. The court temporarily stayed its injunction, meaning the policy will remain in effect until March 11 for review by the Supreme Court.

Customs and Border Patrol this past week sent 160 troops to two ports of entry at the southern border — San Ysidro, California, and El Paso, Texas — in anticipation of the Supreme Court’s review. Officials said that, if the policy is struck down, they anticipate large crowds of migrants will seek entry into the United States.

Individuals who remain in Mexico may wait for months until they are allowed into the U.S., and when they are, they are immediately placed into detention. Asylum seekers are then interviewed by immigration officials to determine whether they have what is called a “credible fear of persecution or torture” in the individual’s native country. If immigration officials are satisfied with the legitimacy of the claim, then the asylum seeker can proceed through the federal immigration court system.

Many asylum seekers navigate the immigration court system while in detention or in Mexico. Under Remain in Mexico, tens of thousands of asylum seekers have been turned back by American authorities into Mexican border cities, where migrants are living in tent encampments. Crime in those cities has surged as migrants have been victimized by sexual assault, kidnap, and torture.

For those who establish a sponsorship with someone in the United States, they can be released from detention and continue the asylum-seeking process while living in the country. Sponsors are U.S. citizens or legal permanent residents who submit paperwork to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to secure an asylum seeker’s release and commit to housing an asylum seeker upon their release.

In 2019, Chinese nationals were granted asylum more than any other nationality, with around 3,600 cases granted. Other top nationalities, in descending order, were El Salvador, India, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Cuba, Cameroon, Nepal, and Venezuela.

From October 2016 to September 2017, there were 55,584 claims of credible fear at ports of entry, according to CBP figures. In that same time span for the following year, there were 92,959 claims of credible fear at ports of entry. A spokesman for the agency said figures for 2019 are still not available.

From October 2018 to September 2019, judges issued decisions on 67,406 asylum cases. Nearly 69 percent of cases were denied asylum relief, according to Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC), a data research center at Syracuse University. On average, asylum applicants wait three years for their cases to be decided. Many wait longer, with a quarter of applicants waiting for four years.

The Department of Homeland Security and President Trump have claimed that immigrant arrivals at the border are at an all-time high, which is not supported by the U.S. government data. From October 2018 to September 2019, there were 859,501 immigrants who crossed the southern border between ports of entry — half of which were families, according to CBP.

Between 2000 and 2007, however, the number of border crossers was consistently near or over 1 million. The number reached as high as 1.6 million in 2000.

Recent statistics show that what is unique about recent years is that the number of families and children seeking asylum has spiked. In 2012, the percentage of families and unaccompanied minors made up 10 percent of apprehended immigrants. Last year, that percentage jumped to 61 percent, according to data released by CBP.

Months in custody

In the month and a half that Ramon spent in Tijuana, he lived in a hotel room and worked at a car wash while waiting for Border Patrol to admit him into the United States for his asylum claim. He waited for his number to be called by U.S. immigration in a process known as the metering system.

The Trump administration began implementing the metering system in April 2018. Under the system, asylum seekers are put on a waitlist at the border and denied entry into the U.S. until their number is called to initiate their asylum claim.

Once his number got called in January 2019, Ramon was detained by U.S. Border Patrol to begin an initial screening process for asylum seekers known as the “credible fear interview.”

During a credible fear interview, asylum seekers must prove that there is a “significant possibility” that they can establish in a hearing before an immigration judge that they face fear of persecution if returned to their country, according to USCIS. Ramon then spent a week in a California detention facility that detainees refer to as “the cold house,” or “icebox,” while waiting for his credible fear interview.

ICE officials out of the Boston office did not return multiple requests for comment regarding the so-called “icebox” and conditions for asylum seekers in detention.

“Conditions there in the first one in California were very horrible,” Ramon said. “We were like 30 in a room with a toilet in a corner, and they gave us a very thin mat and we put it on the floor and paper, like sealing paper — that’s what we used to cover our body and it was very cold in there.”

Before actually having his official credible fear interview, Ramon was transferred to a medical detention center in Arizona — a routine check-up asylum seekers undergo — and then to another detention facility in Mississippi. The credible fear interview took place over the phone while detained in Mississippi, and an immigration agent asked him questions including, “What happened in your home country?” and “Why are you seeking asylum?”

Other questions posed during a credible fear interview, per the USCIS, include: Do you have any fear or concern about being returned to your home or being removed from the United States? Would you be harmed if you were returned to your home country or country of last residence?

A month later, immigration authorities established Ramon had a credible fear of persecution and transferred him to a fourth facility in Georgia to begin the immigration court process for asylum seekers. In order to win his case, he had to include documents to support his claim for asylum, which included an affidavit from his family in Africa and newspaper clippings reporting on the violent attacks in his village.

“Newspapers, affidavit letters from my mother, aunt, and friends,” Ramon said. “And also pictures, death certificates. My brother was killed so I had to mail a death certificate to prove that my brother was dead.”

Ramon navigated the immigration court process without a lawyer, but he had help from a group called the Western Massachusetts Asylum Support Network (WMASN), which helps establish relationships between sponsors and asylum seekers in detention, along with other support services.

Volunteers from western Massachusetts, who went down to the border as part of the New Sanctuary Coalition, formed the WMASN upon their return to the area in early 2019. The New York City-based coalition’s mission is to end deportations and provide support for individuals navigating the U.S. immigration system.

Those volunteers were able to help Ramon gather necessary documents and build a relationship with his eventual sponsor. To this day, the group continues to help him in various capacities. Part two of this series will go more into depth about the WMASN.

Ramon was granted asylum by a federal judge and released from detention in June 2019, five months after being detained at the Mexico-U.S. border. He spent the night of his release in a shelter for asylees in Georgia and the following day boarded a plane headed for Bradley International Airport in Connecticut.

“I was excited for being out of detention,” Ramon said. “It was a dream, but it was also good because I was out and I had to try to contact my family. Throughout this whole time in detention, I spoke with my family just twice.”

Escaping before dawn

In Santiago’s situation, much like Ramon’s, there was not a lot of time for planning. Leaving the country became a matter of survival. In the early hours of a late summer morning in 2018, Santiago had to slip out of the country with little more than the clothes on his back.

Santiago, a man seeking asylum, holds a crucifix at his apartment, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2020, that a friend gave him while they were in detention together.

One of Santiago’s former professors warned him he must leave the country. Santiago had worked for the government and repeatedly refused to take part in activities that not only went against his code of ethics, but which he claims were illegal.

“I was part of an organizing effort against the government due to violations of human rights,” Santiago said. “Even though I am here, my family is there (in Central America) with a lot of things happening to them.”

It was after joining activists who were protesting the government’s seizure of land belonging to indigenous people, however, that the government began sending paramilitary forces and police to patrol his house.

His former professor told him the government had placed him on a list of people not allowed to leave the country. Santiago feared the government wanted to capture or perhaps kill him, as many other activists had been killed.

The government, Santiago said, “began to shoot (activists). They killed a 15-year-old boy. He arrived to bring water to protesters because everyone had spent three days protesting, and when the boy arrived, they put a bullet in his throat.”

The government has continued to retaliate against activists with deadly violence. The protests were also in response to the government raising the age to receive a pension, raising the prices of national health insurance premiums, and the forcible seizure of indigenous people’s lands, according to Santiago.

Before taking part in the protests, Santiago said he had already become something of a thorn in his government’s side for not facilitating what he said were illegal activities. By his account, the government wanted him to falsify records and documents in order to assist in the illegal trafficking of goods, but he refused. He continued publicly decrying the municipal government’s corruption even as he got transferred to different departments until he eventually lost his job.

“I spent seven months without work,” he said. “When I began to work for the government, I began to see the mafia that existed. I am someone who believes that the violation of human rights is something unforgivable. I always, since I began working there, I always said that is not right — even to the mayor.”

Santiago said he would receive threatening messages at his work and at home from the government in retaliation to his involvement with the protests.

‘He told me it’s my problem’

Both Ramon and Santiago had to leave their countries unnoticed by their governments so they had a shot at getting asylum in the United States.

Santiago left his country in late summer 2018 by slipping past the border far away from an official port of entry. He left for Mexico without a concrete plan, and he found life difficult once he got there.

“It was very difficult there (in Mexico) because I had to flee my country in the very early morning without planning so I wound up living on the streets for weeks in Mexico,” Santiago said. “Then, there were people that helped me there to get up to the border.”

By January, he arrived in Tijuana where he met a group of activists orienting immigrants on the asylum-seeking process, the same activists from western Massachusetts that Ramon had met.

He arrived at the office with a group of 12, and from there he began to visit the office on a near-daily basis. The group of activists were doing workshops for immigrants on what they could expect once detained by U.S. Border Patrol. He spent a month in Tijuana, and by the end of his stay, he was helping to run the workshops himself.

Meanwhile, Santiago waited for his number to be called following the Border Patrol’s metering system.

“Sometimes you have to wait a month,” Santiago said. “For others, three months. A month or two is the average. At the port of entry, there is a kiosk and there are people noting why you are there.”

When the day came to cross into the United States for Santiago, he had all his belongings taken by Border Patrol, including his passport, and he got placed in a frigid detention center in California he called the hielera, or “icebox,” where there were nearly 30 others — a similar experience to Ramon.

“We slept on top of each other,” Santiago said, due to overcrowding in the small room. “They would take two out and bring in four. It was very uncomfortable. Without soap, or toothbrushes, or deodorant, you can imagine how one becomes.”

A friend Santiago made while detained in that detention center was deported one morning. Another friend had to go back to Mexico to await his immigration hearing after establishing his credible fear with immigration officials under the Trump administration’s Remain in Mexico policy.

A month after his friend went back to Mexico, Santiago said, his friend found out he had cancer, and since he was undocumented, hospitals in Mexico would not treat him.

“He began getting worse … so he desisted from continuing with his case and he had to return to Central America,” Santiago said.

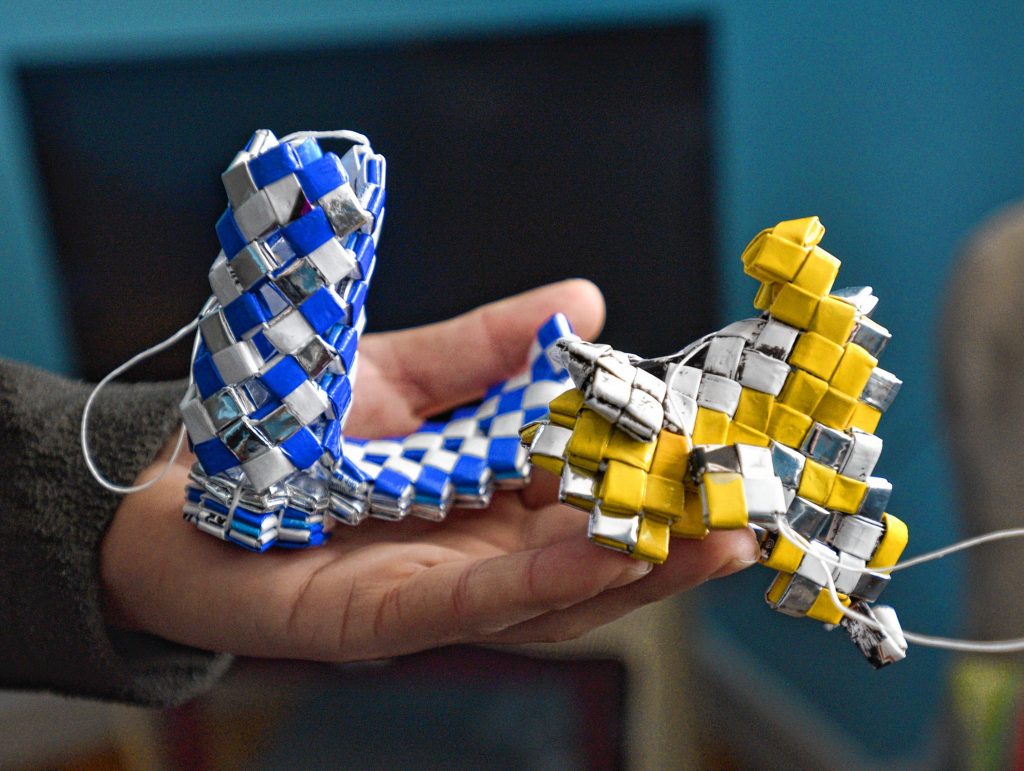

The “icebox” detention center is underground, windowless, and the lights are on at all times, according to Santiago. He said he suffered from insomnia due to the conditions and racism from many of the detention officials. An elderly man was put into solitary confinement one night simply for making small plastic figures out of cookie wrappers.

Santiago, a man seeking asylum, holds a boot and a saddle he made from Oreo wrappers while in detention, at his apartment, Tuesday, Feb. 11, 2020.

“He told us the official that took him had told him that he failed to show him (the official) respect,” Santiago said.

After being transferred to another detention facility in Tacoma, Washington, an immigration agent told him he had to present his passport. Santiago explained that it had been taken by authorities at the border and it was never returned.

That particular agent was a “nasty character,” Santiago recalled. He told of an interaction with the immigration official when he tried to explain to him how he had not been able to recoup his passport from immigration authorities at the border.

“He told me it’s my problem,” Santiago said. “That I don’t care how you got here or why you have come. To me, your life isn’t important. Nor what is happening to you. You have to get this document, and if not, well that’s your problem.”

Santiago’s lawyer managed to contact his sister in his home country and she was able to get a copy of his passport from his house. This allowed Santiago to continue with the application to get out of detention after passing his credible fear interview.

At the last minute, Santiago said immigration authorities added a bond payment of $7,500 as a requirement to be released, and he was forced to pay.

Settling in Western Mass — for now

Santiago had retained a sponsor in another part of the country before being detained. He had met a woman at the border who agreed to house him upon release, which happened in spring of 2019.

He spent the past nine months in a different state, which he asked not to identify, while still going through the federal immigration court process to gain asylum status. He recently moved to the western Massachusetts area and is in a state of limbo while he waits for his next court hearing in spring 2021.

“I’ve been feeling a little bit lost not knowing what will happen,” Santiago said. “I have a strong case but the judge might not be so amiable.”

He said he believes he has less than a 50-50 shot of winning his case.

Ramon likewise is attempting to settle into life in the Valley. His asylum approval within five months of detention is an unusual case. Only 16 percent of unrepresented asylum applicants received asylum during the government’s 2019 fiscal year, running from October 1, 2018, through September 30, 2019, according to TRAC.

Ramon is now living in a rural western Massachusetts town and over the past few months experienced the short days and long nights of a chilling Northeastern winter for the first time. He works in the mornings in a kitchen as a prep cook and spends his days attempting to establish himself in a town that hardly resembles the one he left in Africa late in the summer of 2018.

In the past six months, he has acquired a social security number, started taking driving lessons, attempted to get accustomed to new foods, and is adjusting to a new life in the Pioneer Valley. In his free time, he goes to the gym and is attempting to learn to cook on his own for the first time.

“I am just working now,” Ramon said. “But I am planning on going back to school to study civil engineering and construction.”

Luis Fieldman can be reached at lfieldman@valleyadvocate.com.

Coming next week: Part 2 of the Seeking Asylum in Western Mass series continues with a look at local people who are helping asylum seekers settle here.