It wouldn’t be accurate to say Scott Tulay is moonlighting. The Northampton architect spends a good number of his evenings and weekends drawing, and he earns some money from it, but drawing is much more a passion for him than a second job.

Then there’s the connection between his day job of creating blueprints for new structures, and the off-hours work of making free-form, black-and-white drawings in which he plays with building forms and spatial dimensions to create other-worldly vistas and ambiguous landscapes.

As Tulay says, he once described his work to a friend by saying “I spend my day getting super-detailed about how to put every part of a building together, and then at night I spend my time blowing them apart.”

Though he drew on and off for years, Tulay, a 1988 graduate of Northampton High School, has become more serious about his art in the past 10-12 years and has been steadily winning notice for his work both regionally and further afield, with showings in Boston, New York, San Francisco, London and Berlin.

He recently had a solo exhibit in Venice, Italy, at the same time that the Venice Biennale, a prestigious arts festival that dates to the 1890s, took place.

Tulay, who works out of a studio in Holyoke, says with a laugh that the gallery owner showed his work in Venice, the noted Italian photographer Michele Alassio, “basically said to me, ‘I’m giving you the best time in the world for a show, in the best city in the world for art!’ How could I say no?”

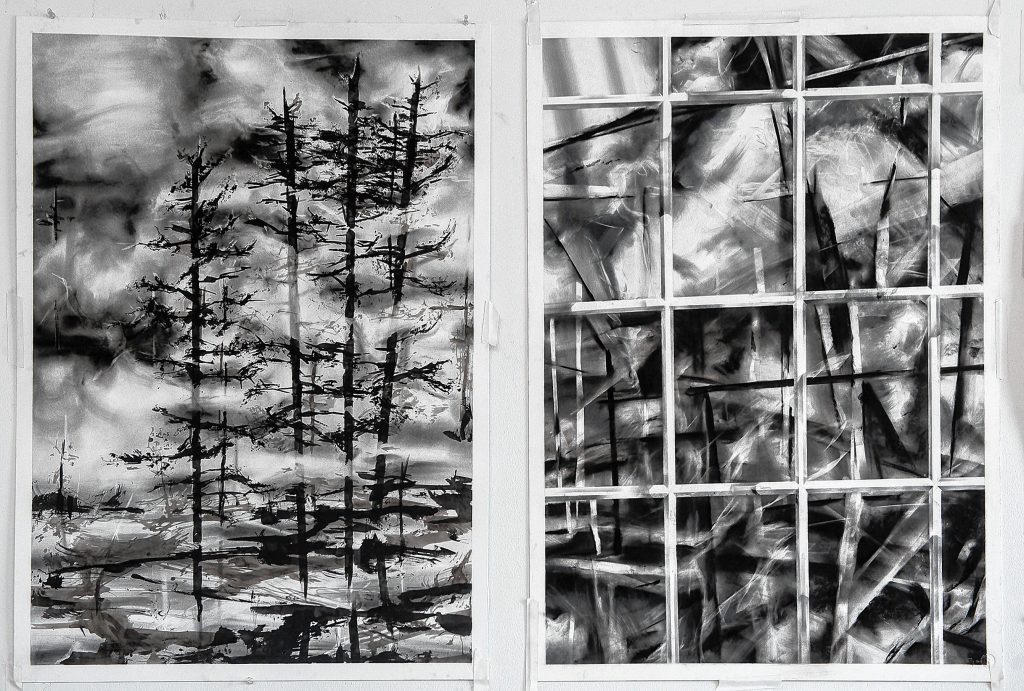

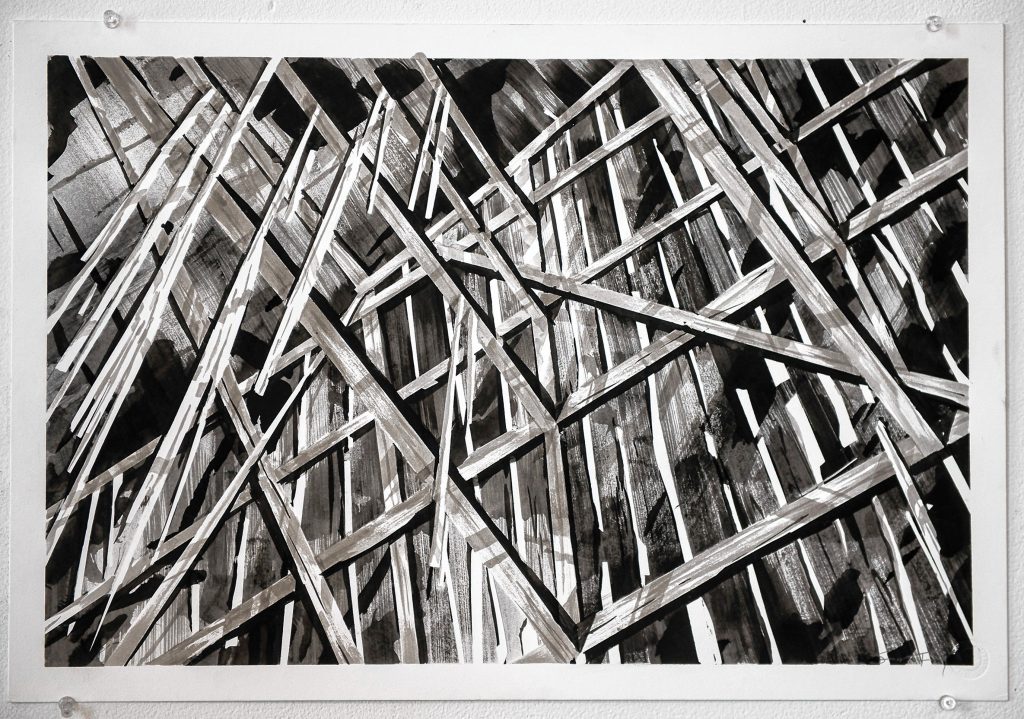

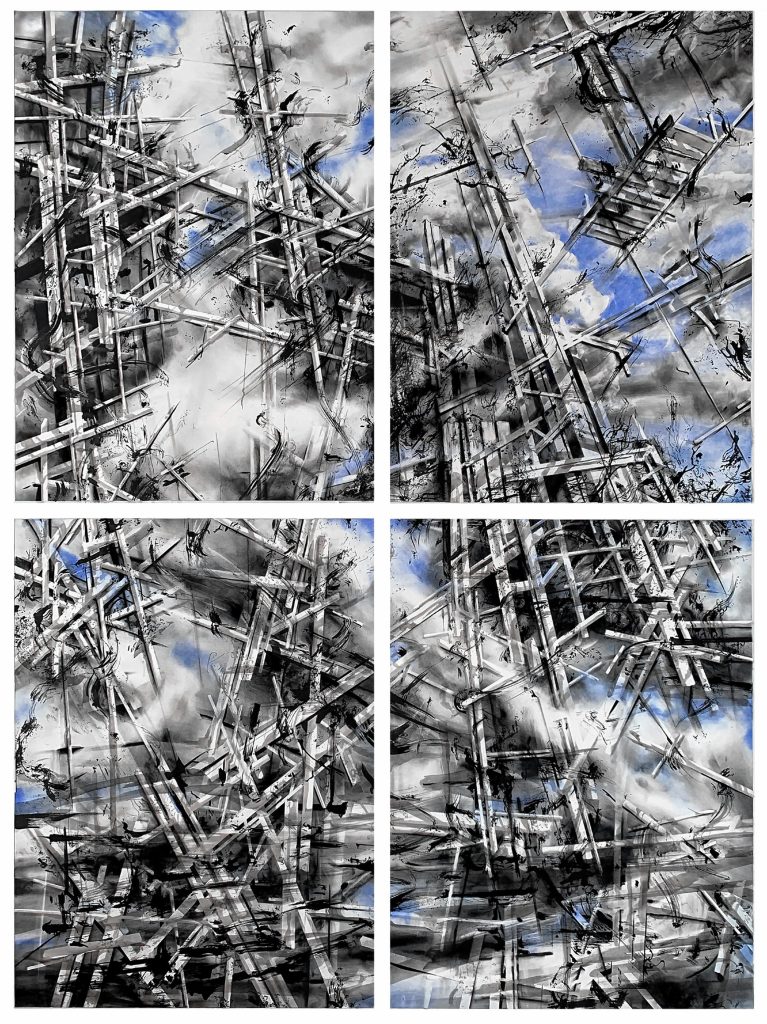

Using a mix of graphite, ink, pen, and paint, as well as some pastel on occasion, Tulay creates layered compositions that offer depth, detail, and energy, with complex, interlocking lines of different contrast and thickness. Some of these works are pulled from his architectural background and feature building outlines, barn interiors, latticeworks, and other somewhat identifiable frameworks.

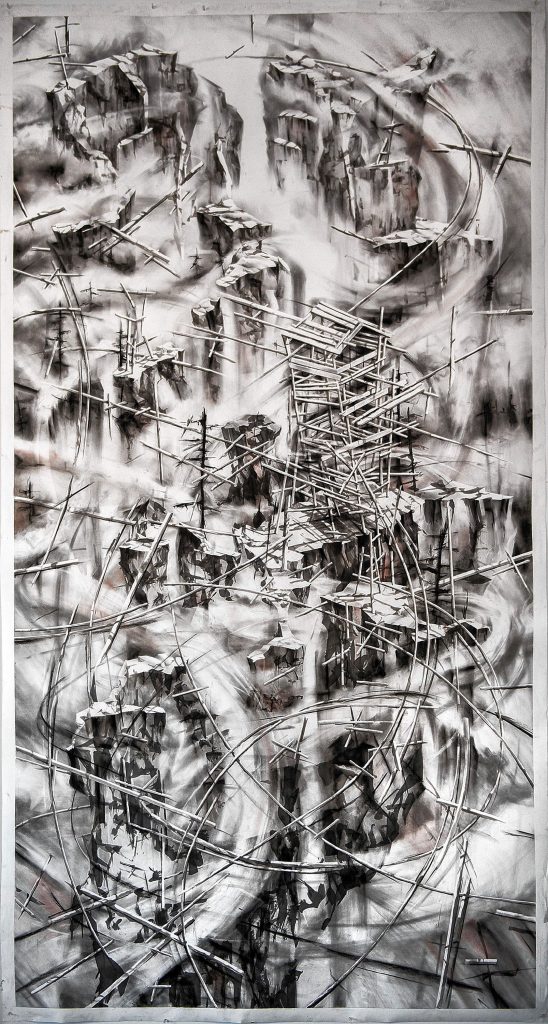

But these “structures” are placed in fantastical settings that can appear post-apocalyptic or just plain ambiguous; many of the images, such as “Explode” and “Untethered,” would be right at home in a graphic fantasy novel or a Japanese anime movie. They’re often back-dropped by swirling, cloud-like forms or a sort of fog that add additional ambiguity to the drawing.

“I really like to play with perspective and spatial relationships, to break down conventional aspects of building construction and kind of turn that upside down or inside out,” Tulay said during a recent interview in his studio.

“Another way to do that is through the treatment of light,” he said, “so as a viewer, sometimes you’re not really clear where you are in respect to the drawing.”

In fact, one of his earliest inspirations for drawing came from seeing the slatted sides of a tobacco barn on his grandfather’s Hadley farm.

“You come in from the sun and inside it’s all cool and shady, and there’s this ethereal light coming through [the walls], and you have this post and beam construction … I always liked that.”

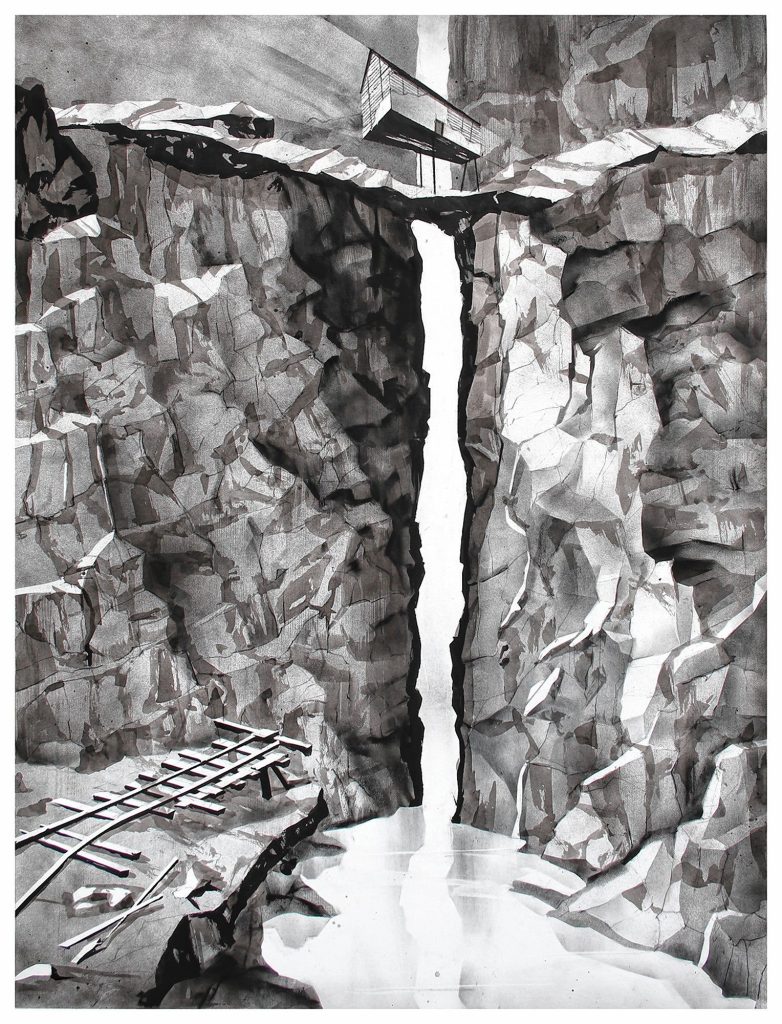

Tulay also constructs imaginary landscapes that can suggest canyon walls and mountains, but again with plenty of uncertainty.

“Weathered Specters,” for instance, presents what appears to be a giant rock chasm with a milky pool at the bottom; a broken railway ends at a rock abutment near the bottom, while at the top of the drawing some kind of rickety walkway (of stone?) stretches above the pool. And is that a house on stilts above the walkway?

A layered constructionThese complex drawings come out of a complex composition process. Tulay starts with white paper that he masks in places with tape or liquid frisket, a material he likens to rubber cement, and then he applies paint, ink, and more with a variety of brushes and other materials such as bits of lace; the latter adds shadowy splashes and tendrils of black to the drawing.

At some point, he’ll remove the tape or frisket to preserve white lines on the drawing but modify them to give them more depth.

Sometimes he’ll cover sections of his paper with gauze and paint over that to add tiny, intricate lines to a drawing; he’ll use cotton balls to brush on a layer of graphite powder to add depth to the work. His website has a short video that demonstrates some of these techniques.

As for subject matter, Tulay says he’s “trying to find a balance between abstraction and more detail. More recently I’m been trying to weave more of those architectural details into my landscapes.”

He also seeks a balance between being an architect and an artist. He works with Juster Pope Frazier, the Northampton company that designed the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art in Amherst and has also designed municipal and college buildings in Massachusetts and other states.

When he was at Northampton High School, Tulay became interested in a career in design; after graduating, he entered an architectural studies program at Tufts University. His studies included art classes every semester at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where he concentrated on drawing, from buildings to figures to landscapes (he did a bit of watercoloring, too). In addition, he studied art history at Tufts.

“I wanted to go to graduate school [for architecture], but I knew I would have to have a portfolio, so studying art was a big part of that,” he said. “Ever since then, I’ve enjoyed drawing by hand, including at work,” though a lot of architectural design now takes place on a computer, Tulay adds.

And over the last 15 years or so, he noted, the more drawing he did, “The more I realized ‘I don’t have to think quite as much as an architect’ when I do this.”

He’s also found inspiration in the work of artists such as Caspar David Friedrich, the Romantic-era German painter; Victor Hugo (the French writer was a prolific illustrator, too); and local hero Leonard Baskin, especially Baskin’s woodcuts.

Today, Tulay hopes to build on some of the connections he’s made in the last several years as he’s exhibited his art more widely. For instance, he met Alassio, the Italian photographer now showing his drawings in Venice, through an exhibit in Berlin that both took part in some years back, at which they were showing work side by side.

“He’s become a friend and a good supporter, and I’m grateful,” said Tulay, who went to Venice in April with his wife and two daughters to attend his exhibit’s opening — his first visit to Italy.

If he could make a living entirely as an artist, he might well opt for that, he noted. That said, Tulay added, “I like working as an architect, and I like being an artist. I like to think I’ve found a pretty good balance between the two.”

To learn more about Scott Tulay’s work, visit scotttulay.org.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.