By STEVE PFARRER

Staff Writer

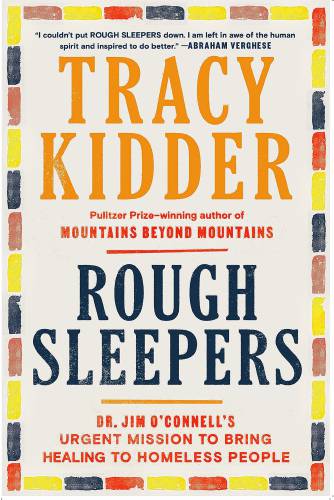

Tracy Kidder’s new book profiles Dr. Jim O’Connell, who since the 1980s has led a program dedicated to providing health care for homeless people in the Boston metro area.

In a long career that’s seen him win a Pulitzer Prize, a National Book Award, and a boatload of praise, Williamsburg writer Tracy Kidder has tackled a number of different subjects: the computer revolution, elementary schools, civil war refugees, the Vietnam War.

One of the nonfiction author’s most memorable titles is “Mountains Beyond Mountains,” a 2003 portrait of the late Dr. Paul Farmer, a Harvard University specialist in infectious diseases who dedicated his life to bringing modern health care to some of the world’s poorest countries.

For his newest book, Kidder has profiled another Harvard doctor who’s also spent his career tending to poor patients in need, this time much closer to home: thousands of people who live on the streets in and around Boston.

To write “Rough Sleepers,” Kidder spent five years following Dr. Jim O’Connell, a Harvard Medical School graduate who since the mid 1980s has led the Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program (BHCHP), which ministers to the most desperate patients in the city.

During a recent visit to Edwards Church in Northampton, Kidder and O’Connell sat down for a discussion, sponsored by Broadside Bookshop, about how the book came together, the flaws in U.S. health care, and what O’Connell called the most important lesson he’s learned during his career: to listen.

Tracy Kidder, seen here in his Willliamsburg home, profiles Boston doctor Jim O’Connell in his new book, “Rough Sleepers.” Gazette file photo

“As a doctor, you’re trained to do the talking, to diagnose problems and tell people how you’re going to help them,” said O’Connell. “I had to learn what people wanted, I had to listen to their stories … it’s very humbling.”

O’Connell began his specialized work in the mid 1980s, following graduation from Harvard Medical and a residency at Massachusetts General Hospital. As Kidder’s book outlines, the hospital’s chief of medicine asked O’Connell if he’d defer a prestigious fellowship and spend a year helping to create an organization to bring health care to homeless citizens.

O’Connell noted that he felt he couldn’t refuse. But that year turned into a career, he said, because he saw such a huge need for providing health care for a population that otherwise was ignored — and because to provide that help gave him a sense of joy.

“If you don’t get joy out of this, you’re in the wrong profession,” he said.

O’Connell also flashed a quick sense of humor in his talk, describing how he and his team — today the BHCHP numbers over 600 medical and behavioral health staff, social service workers, and others — had to learn early on that people living on the streets might not see them as knights in shining armor, at least at first.

“We’d hear things like ‘How’d you like it if your doctor showed up at your bed at two in the morning, asking how you were doing?’ ” he said as the the audience laughed along.

‘Doctah Jim! How are ya!’

Yet a very funny anecdote at the beginning of “Rough Sleepers” highlights O’Connell’s bona fides with the people he tends to. One warm September night, the driver of a van with O’Connell and a few other health workers approaches a lumpy figure buried under multiple blankets by a South Boston loading dock; the driver tells the person he’s doing a wellness check.

From beneath the blankets comes a terse reply: “(Bleep) you. Get the (bleep) outa here.”

So O’Connell gives it a try: “Hey, Johnny. It’s Jim O’Connell. I haven’t seen you in a long time. I just want to make sure you’re all right.”

And as Kidder describes, suddenly a man with “(t)angled hair and a bright red face” becomes visible from beneath his blankets, saying in a loud, Boston accent, “Doctah Jim! How the (bleep) are ya!”

For his part, Kidder told the audience at Edwards Church that following O’Connell and his team for five years opened his eyes to the scope of the homelessness problem in a way that news reports and facts and figures hadn’t.

“Don’t believe the numbers you hear,” he said. “The problem is much worse … there are at least one million schoolchildren who are homeless” across the country.

Kidder said reporting the story also illustrated for him the terrible inequities in health care in the United States, where you have “basically a Third World nation living in the shadow of Mass General.”

“The corporate model of health care is based on doctors being efficient with patients, moving on to the next person as quickly as possible,” he said. “What Jim and his people do is exactly the opposite … they spend time with them, they get to know them.”

“It was amazing to go out with Jim and talk to the people he helped, and have four of them in a row say Jim’s their best friend,” Kidder added.

Boston Dr. Jim O’Connell, left, with Williamsburg writer Tracy Kidder at Edwards Church in Northampton, where the two spoke about Kidder’s new book, “Rough Sleepers.” Photo courtesy Broadside Bookshop

As Kidder said in a Gazette interview a few years ago, when he was working on the book, O’Connell is “maybe the most beloved person on the nighttime streets of Boston, except for David Ortiz.”

“Rough Sleepers” — the title comes from a 19th century British term for people who live on the streets — explores the difficulties O’Connell has faced trying to help people who may also be battling mental illness, chronic addiction, or threats from violence.

As Kidder writes in one section, O’Connell’s “patients, and prospective patients, were sleeping in doorways, arguing drunkenly with statues in parks. I had rarely spoken to such people and congratulated myself when I had.

“For me, the night’s tour was a glimpse of a world hidden in plain sight. I was left with a memory of vivid faces and voices, and with a general impression of harsh survival, leavened by affection between a doctor and his patients.”

In the book, O’Connell relates that most of the patients he’s gotten close to during his career are now dead: “So there’s a certain sadness and moral outrage that I can’t get rid of. But when you work with people who’ve had so little chance in life, there’s a lot you can do. You try to take care of people, meet them where they are, figure out who they are, figure out what they need, how you can ease their suffering.”

O’Connell, who’s also an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical, said he’s remained committed to helping homeless patients, despite the overwhelming scope of the problem — he and his team minister to approximately 11,000 people — because to not do so would seem a betrayal of all he’s learned from the experience.

As “Rough Sleepers” notes, one of O’Connell’s first jobs was to soak the feet of residents of a homeless shelter — and to do so under the supervision of nurses.

“I’ve had to learn to respect boundaries, I’ve had to earn people’s trust, and I’ve had to learn to listen,” he said. “It’s been quite a journey.”

More about Tracy Kidder’s new book and his other works can be found at tracykidder.com.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.