When Barack Obama was elected president in Nov. 2008, Ousmane Power-Greene recalls having a terrible thought: that a racist might try to assassinate America’s first Black president, or maybe his whole family.

Perhaps that was an overly morbid vision, Power-Greene remembers thinking. Yet just hours after Obama’s win, three white men burned down a mostly Black church in Springfield in retaliation (all three were eventually given prison sentences between 4 and 14 years).

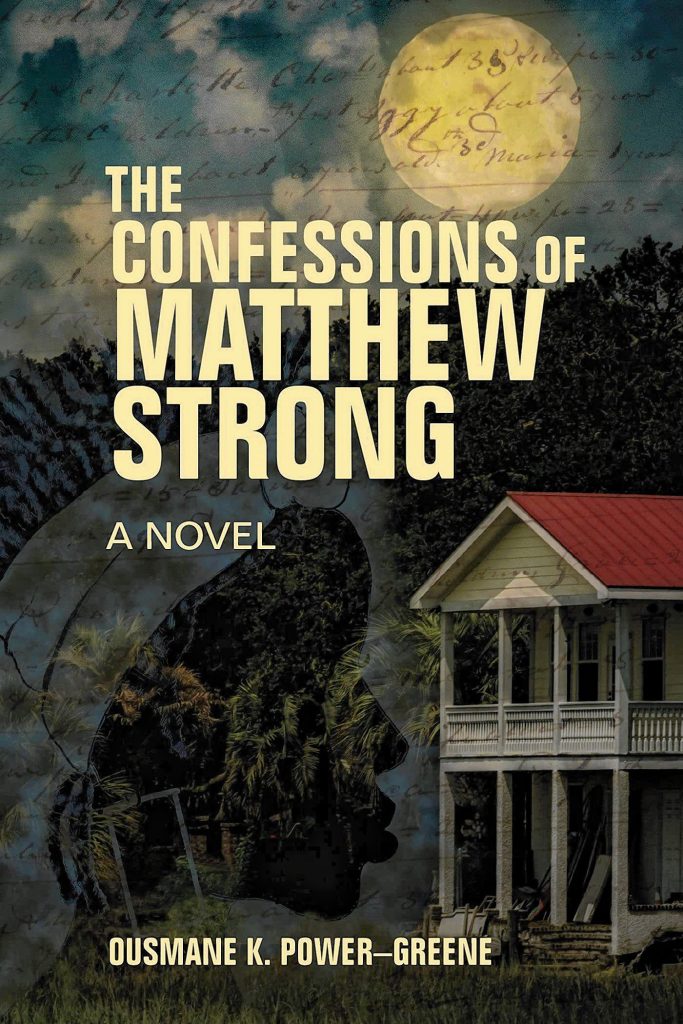

Those events were the starting point for Power-Greene’s sobering debut novel, “The Confessions of Matthew Strong,” a thriller that explores ideas such as race and redemption as well as the history of slavery and Jim Crow violence in the U.S. South.

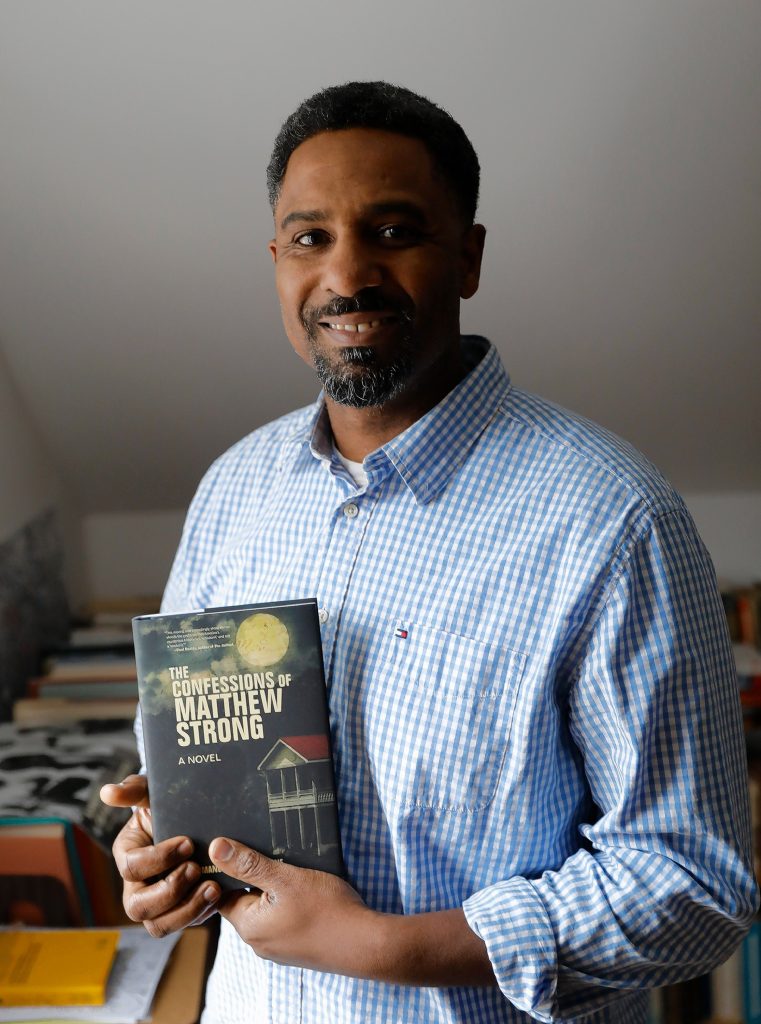

And Power-Greene, who lives in Northampton and teaches at Clark University in Worcester, raises another question in his book: How does the Black community in particular confront a rise in white supremacist thinking and action?

At the heart of the story is the narrator, Allegra “Allie” Douglass, a successful Black philosophy professor and writer who teaches in a university in New York City. While visiting her hometown in Alabama after her grandmother dies, she’s kidnapped by a white supremacist who’s built an underground movement that he imagines will restore the glory of the Antebellum South.

Sound far-fetched? Power-Greene, in a recent interview, said that might seem the case to some. Yet as he was writing the book, especially after Donald Trump became president in 2017, the boundaries of what might have seemed implausible in modern U.S. society “kept getting stretched. And then came January 6, 2021, and we realized how many barriers had been broken.”

“We’ve witnessed some very frightening events in the last several years,” he added, pointing as one example to the massacre of nine Black members, including a state senator, of a South Carolina church in 2015 by avowed white supremacist Dylann Roof.

“I think we ignore white supremacy at our peril,” said Power-Greene, a South Carolina native.

The NPR program “Books We Love,” for one, called “The Confessions of Matthew Strong” one its favorites of 2022 (the novel was published last fall) saying “The racial violence in the story is raw and unsettling, but it underscores the message here — that radical ideology is an enemy to be taken seriously.”

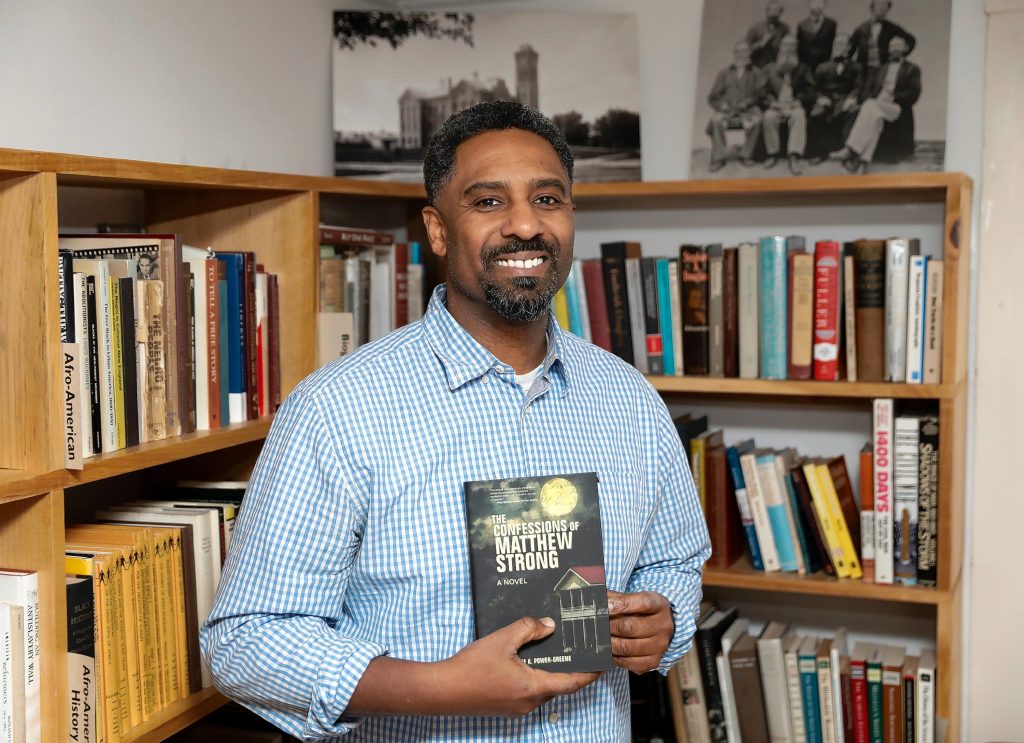

Today Power-Greene teaches history and directs the Africana Studies program at Clark University; he received his doctorate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where he was part of the W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies.

He previously published “Against the Wind and Tide” (NYU Press), a study of early 19th century Black activists and leaders who opposed the white-led “colonization” movement to move African Americans to Liberia, under the premise that they would never be granted full citizenship in the U.S.

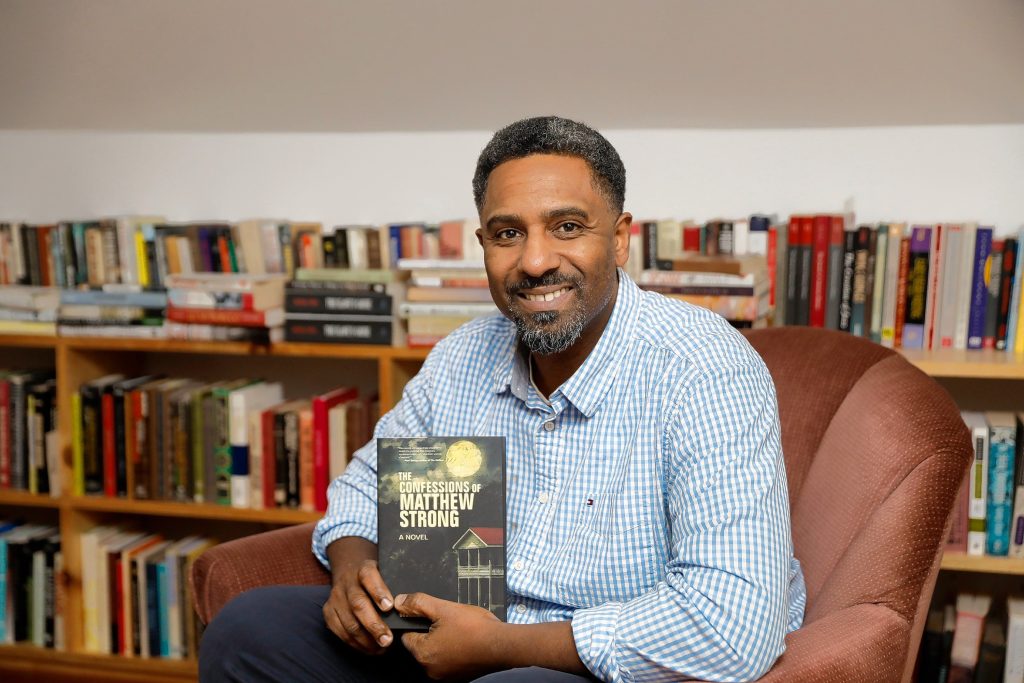

But Power-Greene said he’s also been writing fiction for years — “It was kind of my first love” — and as he considered the growth of right-wing militias and white supremacist thinking in the U.S. in the past decade-plus, as well as his own research on slavery and the post-Civil War South, he began thinking a novel might be the best means for tying together these different themes.

“With fiction, you can create a narrative to bring cohesion to all these events,” he said. “And I think you can introduce these ideas to readers in an easier way than through a more academic book.”

A tortured history

The story begins in New York, where Allie, who has made her name by studying the philosophy of slaveholders in the pre-Civil War South, is awarded a distinguished chair in her university’s philosophy department.

For Allie, that award is a welcome acknowledgement of her scholarship, which she feels has been denigrated by her department chairman, among others at her university.

Yet the award, which comes as part of a large donation to the school from a Southern foundation, also arrives when Allie is troubled by other events. A graduate student she was friendly with, Cynthia, has gone missing, and one member of the white family foundation that’s donated money to the university tells Allie bluntly that he was opposed to giving her the award.

“But be careful, there are some in our family who are less gracious than I,” he tells her at a reception. “Some who’d die before they see you honored by an award named after a member of our family.”

Perhaps worse, Allie has begun receiving cryptic notes from someone who signs his letters “William Shields, Esq.” She realizes that a notorious Southern vigilante who killed and threatened Blacks in the post-Civil War South had the same name, a man who’d been the son of a prominent slaveholder.

Before long, Allie has to fly to her childhood home outside Birmingham, Alabama when her beloved grandmother, who raised her, dies. Returning to Alabama reignites tensions between Allie and her older sister, Janice, who believes Allie turned her back on the family in her quest for academic stardom.

“I wanted to tell an intergenerational story,” said Power-Greene. “That’s something that’s been really important in my life.”

Power-Greene says he based Allie in part on Angela Davis, the longtime writer, educator and political activist, and other noted Black women who fought white supremacy, from the abolitionist Sojourner Truth to the journalist and activist Ida B. Wells.

“I think strong Black women are central to this whole story,” he said.

Allie will certainly need strength as she confronts growing threats in Alabama. She learns her grandmother was involved with other local activists in trying to trace numerous missing young Black women from the community, including Cynthia. Local law enforcement doesn’t seem all that invested in the case.

And when Matthew Strong, the delusional white supremacist, makes his move, the story takes a frightening turn: Allie must confront a man who’s gathered numerous followers to restore old plantation homes and mete out ritualized violence to “inferior” people and white “traitors” alike.

Power-Greene says a great-grandfather on his mother’s side of the family was nearly lynched in the South decades ago — yet he never heard that story until he was an adult.

“I think there’s a certain amount of trauma and pain that a lot of Black families carry,” said Power-Greene. “How we discuss those stories and how we come to terms with them is important, especially when we consider the rise in extremism and white supremacy.”

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.