By STEVE PFARRER

Staff Writer

Joe Farnsworth was 10 or 11 when he got the chance to meet a drumming legend: Max Roach.

It was at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, in 1979, where Roach taught. Farnsworth, who grew up in South Hadley, remembers how one of his older brothers, John, a saxophonist, took him to see Roach perform, and the two were able to meet Roach backstage as well.

Joe Farnsworth, who over the years has forged his own successful career as a busy jazz drummer and bandleader, has never forgotten that encounter.

“I spent years emulating Max when I was a kid, I loved watching his drum solos, and I wanted to learn them all,” said Farnsworth, who lives in New York City. “And when I was older and began playing (professionally), I still loved watching him — just the way he’d come into the room and walk onstage.”

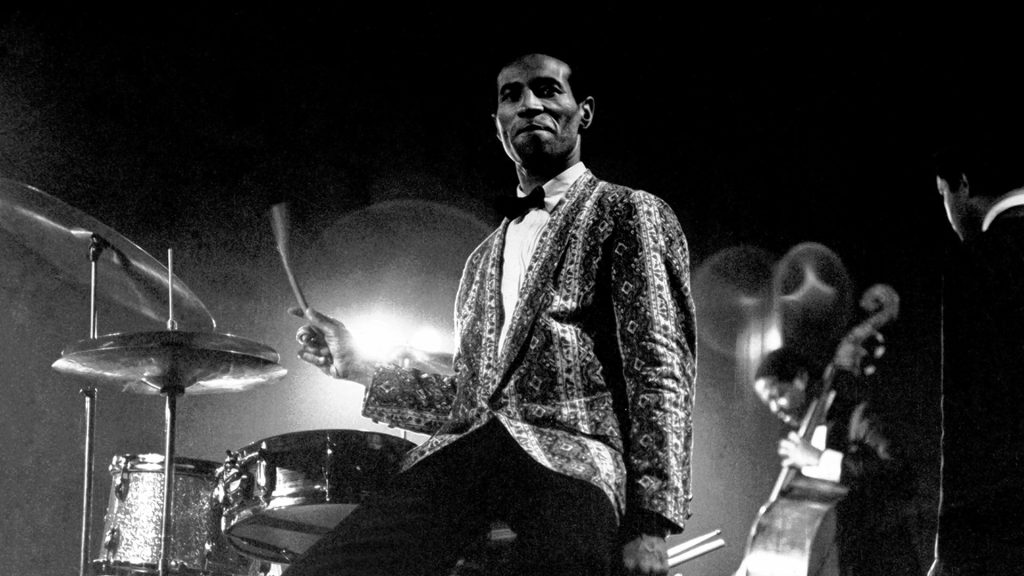

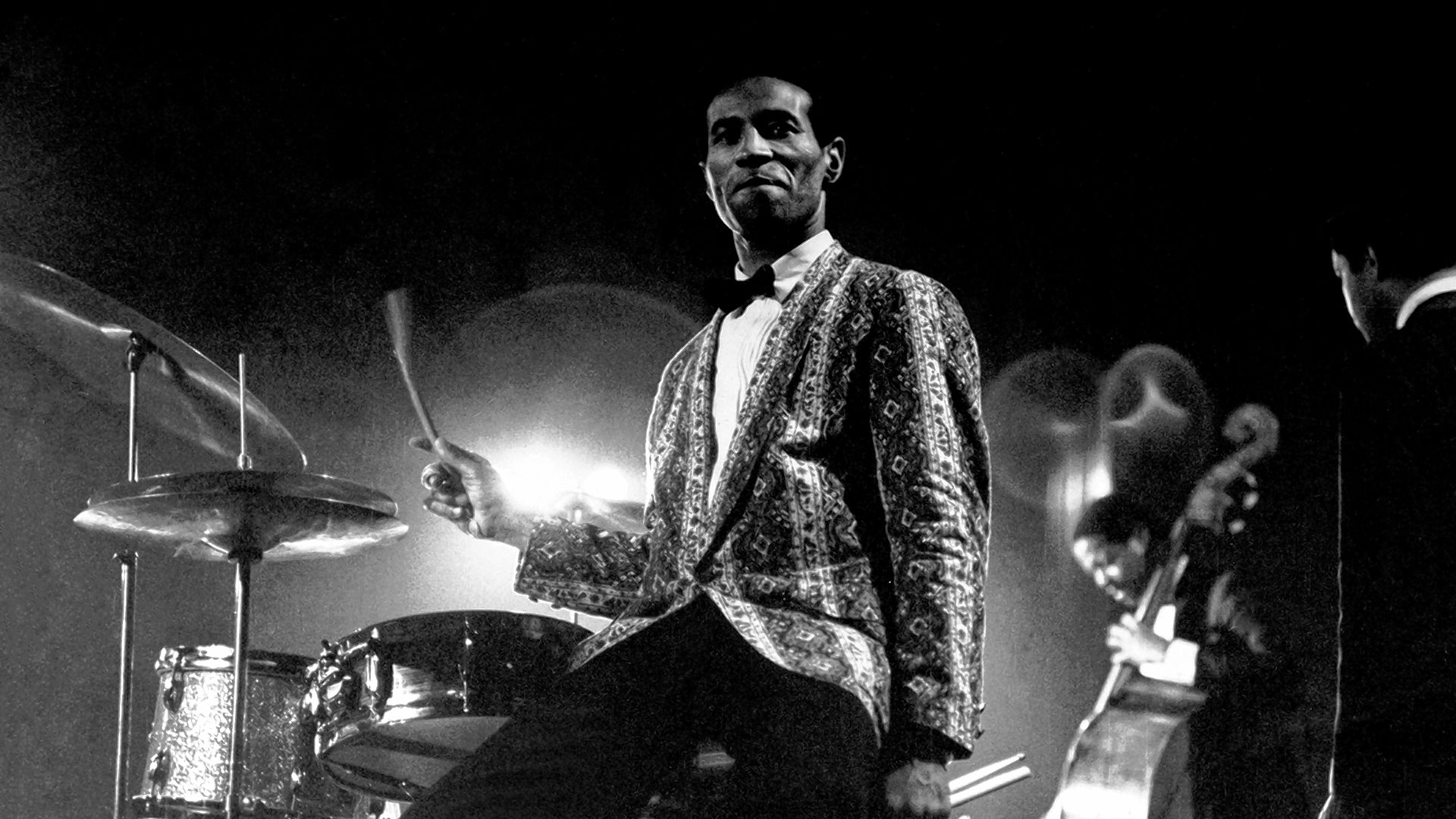

Image courtesy of The Film Collaborative

Legendary jazz drummer Max Roach was the biggest inspiration for South Hadley native and fellow drummer Joe Farnsworth, who will lead a quintet at the 2023 Northampton Jazz Festival in a concert that celebrates Roach’s centennial.

And now the circle is turning, so to speak. At this year’s Northampton Jazz Festival (NJF), at the end of September, Farnsworth’s ensemble will be the headline act, playing a show that will honor Roach, who died in 2007, on the cusp of his centennial (he was born in January 1924).

“To be coming back to the place where I grew up, to play a concert celebrating a guy I’ve idolized for so long — it’s like heaven on earth,” said Farnsworth, a two-time Grammy nominee himself.

Image from Joe Farnsworth website

Jazz drummer and South Hadley native Joe Farnsworth will lead a quintet at the Northampton Jazz Festival in September at a concert honoring his hero, the legendary drummer Max Roach.

It’s not hard to see how a jazz drummer — or any drummer, really — might idolize Roach, who was born in North Carolina in 1924 but raised primarily in Brooklyn, New York. He’s considered one of the pioneers of bebop, alongside other titans like Charlie Parker, and he played with myriad jazz greats — Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Charles Mingus — and led groundbreaking ensembles in every decade of his long career. As a drummer and a composer, he’s credited with making drums a more expressive instrument in jazz.

Farnsworth, who’s 55 and has lived in the Big Apple for over 30 years, has been inspired and mentored by many other players over the years, some in the Valley and some who he met along his professional journey.

One is saxophonist George Coleman, now 88, who will be part of Farnsworth’s quintet at the Sept. 30 NJF show at the Academy of Music. Coleman is a legend as well, an NEA Jazz Master who played with B.B. King as a teenager before moving on to gig with Max Roach and many other jazz players; he was part of Miles Davis’ landmark quintet in the early 1960s.

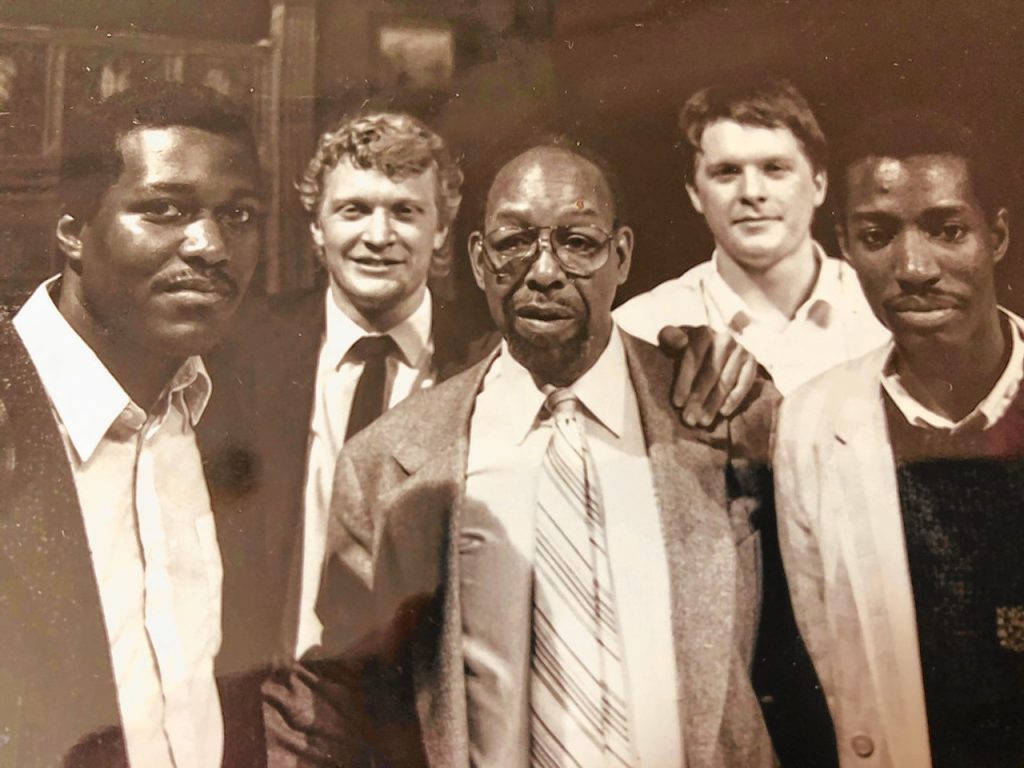

Image courtesy Northampton Jazz Festival

Veteran saxophonist and NEA Jazz Master George Coleman, who got his start playing with B.B. King in the 1950s, will join Joe Farnsworth for a concert at the 2023 Northampton Jazz Festival that will honor legendary drummer Max Roach.

Coleman in turn is just one of many luminaries Farnsworth has gigged, recorded or toured with at some point in his career, a long list that includes McCoy Tyner, Wynton Marsalis, Harold Mabern, Horace Silver, Diana Krall, Benny Golson and Pharoah Sanders.

He’s played on dozens and dozens of jazz albums by other artists and numerous others as a band leader. His most recent album, “In What Direction Are You Headed?” on Smoke Sessions Records, has earned excellent reviews for the way in which he melds his patented bebop sound with the sensibilities of younger musicians. The album features heavy hitters, such as guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel, and young lions, like Blue Note saxophonist Immanuel Wilkins.

“(Farnsworth’s) style is deeply rooted in the bebop and hard bop traditions, characterized by a driving rhythmic feel, impeccable timing, and an expressive approach to improvisation,” writes All About Jazz. “This recording represents Farnsworth removing his ‘blinders’— his word — by embracing a younger generation of musicians … the direction Farnsworth is heading is new and exciting.”

His versatility can be traced at least in part to growing up in a household filled with music — all kinds, but with an emphasis on jazz. His father, Roger, was a well-known music teacher who immersed his five sons in music.

Image from Joe Farnsworth website

Over the years, Joe Farnsworth has won much praise for a style that combines speed with precision and melodic playing. Downbeat Magazine calls his work “the epitome of solid, swinging time-keeping, played with a light touch while maintaining … an irresistible groove.”

Joe, as the youngest brother, got plenty of inspiration from hearing what was playing in his siblings’ bedrooms.

“David, who was also a drummer, would be listening to Buddy Rich, Count Basie, and he also liked that kind of crossover pop-soul sound, like Marvin Gaye and Earth, Wind & Fire,” he said. “James, who played saxophone, would have on Sonny Rollins. John played sax, too, and he’d be listening to John Coltrane.”

His fourth brother, Paul, “was more of a rock and roll guy,” he added. “But we all loved music in some way, and jazz especially just made it feel like a party to me. It was a feeling that gave me hope.”

He figures there were probably 15,000 records in the house: “There aren’t too many jazz records I haven’t heard.”

Another memory: sneaking into David’s room when that older bro wasn’t around to have a go at his drums, when he was no older than five, even though David had warned him “not to touch his drums.”

Image courtesy Joe Farnsworth

Joe Farnsworth, third from right in second row, was a busy jazz drummer in his days at South Hadley High School in the mid 1980s.

Learning from the pros

Farnsworth took lessons from a number of drummers as he was growing up, including Jim Cote of South Hadley, and he was inspired by other noted jazz players in the area, such as saxophone great Archie Shepp, who like Roach taught at UMass, and Charles “Majeed” Greenlea, a trombonist who gigged with Shepp.

After playing with the jazz band at South Hadley High School, and doing some paying gigs as well, Farnsworth studied music at William Paterson College in New Jersey, working closely with jazz drummers Arthur Taylor and Alan Dawson, as well as pianist Harold Mabern.

Image courtesy Joe Farnsworth

Joe Farnsworth, in back row at right, with his brother John, back row at left, after a gig the brothers played in 1988 with, from left to right in front, trumpet player Wallace Roney, trombonist Charles “Majeed” Greenlee, and saxophonist Antoine Roney.

And when he wasn’t taking classes and rehearsing, Farnsworth says, he headed over to Manhattan, just 20-odd miles away, to check out the clubs; his brother John lived there, working as a professional musician, so he had a place to stay.

“There was so much music to hear, so much to take in,” he said. “It was basically music in New York all weekend, then back to school by Monday morning … I didn’t get a lot of sleep in those days.”

In that sense, he was following in the footsteps of his idol. In a documentary he made a few years ago about Max Roach, Farnsworth begins the narration from the street in Brooklyn where Roach grew up, describing how the drummer played music in clubs at night as a teenager, then dragged himself to school the next day.

Farnsworth said he moved to New York for good in the early 1990s and began playing professionally with the help of some of the masters he’d trained with. Mabern, the pianist, got him some early gigs, and through that he met George Coleman, who hired him as well. They’ve been colleagues and friends ever since.

Over the years, Farnsworth has won much praise for a style that combines speed with precision and melodic playing. Downbeat Magazine calls his work “the epitome of solid, swinging time-keeping, played with a light touch while maintaining … an irresistible groove.”

Photo courtesy Joe Farnsworth

Joe Farnsworth, left, with pianist Brad Mehldau and bassist Christian Mcbride after a gig earlier this year at the Village Vanguard in New York.

He’s done plenty of teaching, too, leading jazz clinics and masterclasses at college and universities. He’s played on occasion in the Valley — he recalls a gig at the Iron Horse Music Hall years ago — but in general, he notes, his visits to the region have mostly been to see family and old friends.

“That’s another reason coming back to play at the Academy of Music is such a thrill,” he said.

For the Sept. 30 Max Roach Centennial Concert, he’ll be joined by Coleman on saxophone, Christian Sands on piano, Jeremy Pelt on trumpet, and Peter Washington on bass.

Farnsworth says he’s grateful to the festival organizers for hosting him and his quintet and for all the teachers and mentors he had when he was growing in the Valley — and his greatest inspiration, Roach himself.

“That goes without saying,” he noted.

More information on the 2023 Northampton Jazz Festival is available at northamptonjazzfest.org.

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.