By STEVE PFARRER

Staff Writer

A Fool’s Journey: To the Beach Boys & Beyond

By Carli Muñoz

Interlink Publishing

Jazz pianist Carli Muñoz has had a long and successful career in music, both as a jazz and blues player but also logging time with rock and pop bands, and even some country and bluegrass groups.

Now in his 70s, Muñoz has accumulated enough war stories from the road and some hard-earned wisdom to pen a memoir, “A Fool’s Journey,” published by Interlink Books of Northampton.

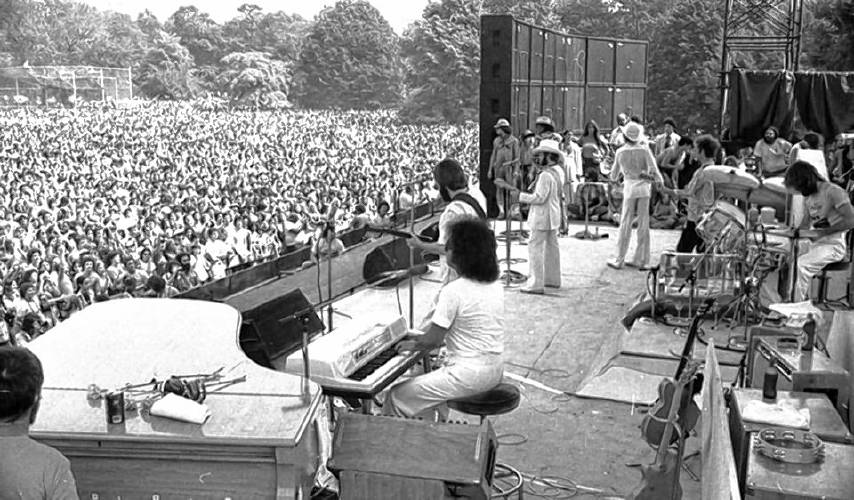

In particular, Muñoz spent about 12 years touring with the Beach Boys, from the late 1960s to early 1980s, first as a percussionist and then as their main keyboard player. His memoir offers an inside look of what it was like to play with one of America’s iconic pop bands.

That part of the story ended on a sad note, especially after Muñoz developed a close relationship with the group’s drummer, Dennis Wilson, whose hard-partying ways led to his death by drowning in 1983, when he was just 39.

Muñoz, born in 1948 in San Juan, Puerto Rico, relates a pretty happy childhood that included what would be a life changing moment: His father gave him a piano as a gift when he was 13, and Muñoz immersed himself in music, teaching himself how to play by listening to records.

A few years later, he got his first break when he was asked to sit in with a jazz band at a San Juan club after the bassist didn’t show up. Bluffing his way through the set, Muñoz acquitted himself well enough on bass that the band asked him if could play piano, too, and he was later asked to replace the group’s former pianist.

This being the 1960s, Muñoz’s memoir touches on the social changes and experiments taking place in those days, which he was soon caught up in, such as taking LSD. “Thrill seeking was the norm,” he writes. “I became obsessed with LSD.”

In the late 1960s, now playing with a psychedelic rock band in Puerto Rico, he and his mates suddenly moved to New York City, beginning a sex-filled but precarious existence for a year or so that would eventually see Muñoz living on the street for a time before he returned to his parents’ house to recuperate.

Muñoz writes in a straightforward, conversational style, explaining how a turn to vegetarianism, spirituality, and astrology — he names his book’s chapters after tarot cards, including “The Fool”) — helped him pull his life back together. Then a trip to California with a friend started another chapter, this time with the Beach Boys.

A good chunk of his memoir is devoted to that era, so readers get another look at the fabled band and its inner turmoil: Brian Wilson’s mental health issues, the growing friction between singer Mike Love and the Wilson brothers, and the drug problems of Dennis Wilson.

Among the anecdotes Muñoz relates is Brian Wilson grabbing and devouring a piece of beef fat off Muñoz’s plate one night at dinner; Carl Wilson nursing a swollen jaw after one of Brian’s bodyguards slugged him during an argument; and Dennis Wilson engaging in various excesses.

“Dennis was a tragedy waiting to happen, and it was just a matter of when,” Muñoz writes of his friend’s death. “Still, it was a devastating blow to everyone who knew him and loved him.”

But “A Fool’s Journey” also recounts the joy Muñoz had performing with the Beach Boys and with many other musicians over the years: Wilson Pickett, George Benson, Rickie Lee Jones, and Les McCann, to name a few.

Muñoz eventually moved back to Puerto Rico, opened a restaurant and jazz club in San Juan where he still plays regularly, and recorded a number of well-received jazz albums with his quartet beginning around 2000.

“Looking over where I’ve been — from my happy and careless youth to going to hell and back — a sense of completion surrounds me,” he writes. “Now that I’m past living on the edge, I feel fortunate to have made it through the thick of it. I’ve found beauty and balance in my life.”

Carli Muñoz will give a free talk and jazz concert Oct. 5 at 7 p.m. in Sage Hall at Smith College. The event, presented by Interlink Books and the Massachusetts Review, will include a conversation between Muñoz and Jim Hicks, editor of the Review.

A Boston Love Story

By Larence B. Siddall

Pelham Springs Press

Amherst resident Lawrence Siddall, a former psychotherapist who earned an Ed.D from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, did something unusual after he retired in the late 1990s: He taught high school English in Poland as a Peace Corps volunteer.

It’s an experience he chronicled in his 2008 memoir “Two Years in Poland and Other Stories,” a book that also recounted some of his other history, including some world travels (he was born in 1930 in China, where his father was a medical missionary). He’s also written nonfiction for other forums.

Now Siddall, who’s in his early 90s, has taken his first stab at fiction with “A Boston Love Story,” a novel he began in 2019 in part because of his own experience being declared legally blind several years ago.

“I was fascinated with how someone who sustains a facial disfigurement deals with this life-altering injury,” he writes in an introduction to his new book, noting that the idea may also have come from his own experience with impaired vision.

In “A Boston Love Story,” 47-year-old Luke Shorason, an editor with a venerable text book publisher in Boston, has recently developed a relationship with Rosa, a curator of American art at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Their affair gets off to a gradual start but then warms; Luke is grateful, given his previous marriage ended badly.

But not long after the couple spend their first night together, Luke is sideswiped by a truck while bicycling and thrown down a slope that’s littered with construction debris; he suffers multiple injuries, including severe lacerations to his face.

It’s not until a few days later that Luke gets the full story about the injuries to his face: The doctors tell him the wounds will heal but that some of the scarring will likely be permanent.

“I’m shocked when I look in a mirror,” he tells a psychologist who asks him how he’s coping with things mentally and emotionally. “With all these stitches in my face, I’m a freaking horror show.”

What’s even scarier for him is how Rosa will react to his wounds. Have they been together long enough for her to have formed enough of an attachment to him to overcome his disfigurement?

It’s a question Rosa wrestles with as well. She’s shocked at how Luke looks but wonders if her reaction makes her shallow — even as her sister, Sheila, tells Rosa “you are not married to this man. You have known him for less than a year … you are under no obligation to stay with him.”

But Sheila also says, “If you really like this guy, that’s a different story altogether.”

How Luke, Rosa, and their friends and families negotiate this uncertain terrain is at the heart of the stately “Boston Love Story,” which examines how people deal with unexpected hardship and what they find important in their lives.