By STEVE PFARRER

Staff Writer

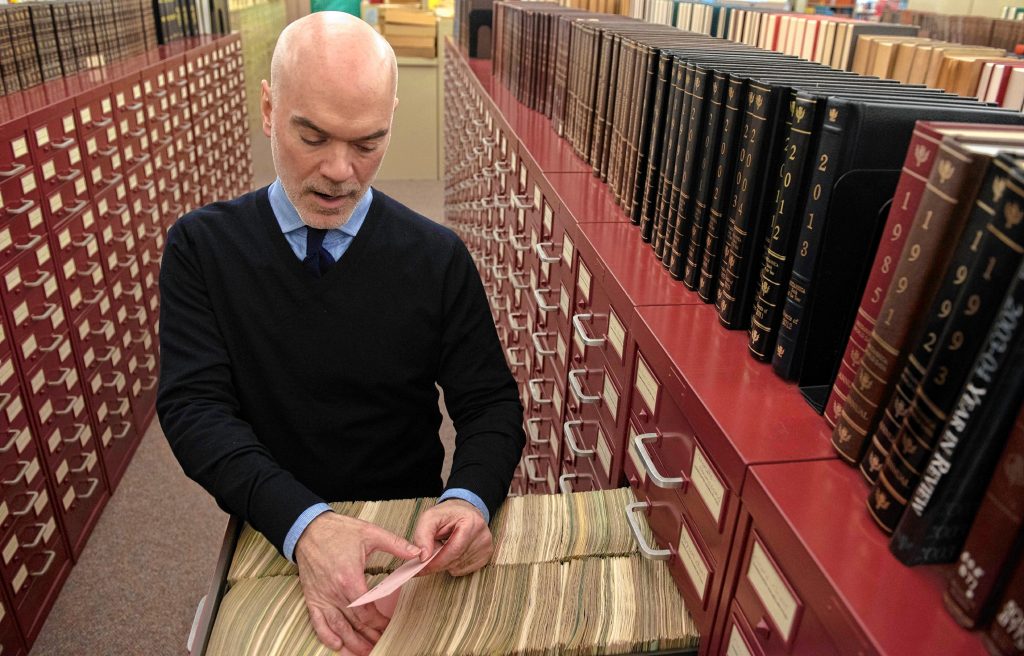

Merriam-Webster has a very active online presence today. But in years past, as Peter Sokolowski explains, decisions on adding new words to the dictionary generated vast paper records, called citation files, as seen here in the company’s Springfield headquarters. STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

When Peter Sokolowski started work as an editor at Merriam-Webster 30 years ago, about 80 people worked at the venerable dictionary company in Springfield, including about 45 editors.

But based on how quiet the offices were, it might have seemed the company employed just a handful of people. No one had a phone at their desk; if you needed to touch base with another worker, you wrote notes that would be picked up twice a day by someone who passed them to the other person.

“There was utter silence,” Sokolowski, 54, said during a recent interview at Merriam-Webster. “It was like a library.”

Today, the Merriam-Webster offices, in a circa 1940s building that looks like an old school, remain quiet, in part because there are fewer employees, and many work from home part of the time. But the company has a lively online presence, with a website full of amusing videos, blog posts, word quizzes and quirky information about unusual terms.

You can watch Peyton Manning, the former NFL quarterback and ubiquitous TV pitchman, talk about the word “Omaha” and how it’s not just a city in eastern Nebraska but the word he shouted at the line of scrimmage when he called an audible. Or check out the link to “Rare and Amusing Insults” such as “Innumerate” (ignorance of mathematics).

“The online dictionary is kind of like a language magazine,” said Sokolowski.

Merriam-Webster also has busy Twitter and Instagram accounts, with all this activity geared to celebrating the ins and outs of the English language and showing that lexicography can be fun.

And today, Sokolowski, hired as an editor and translator for Merriam-Webster’s first French-English dictionary, is the public face of the company — one of the few American dictionaries left in what was once a pretty competitive business.

As editor at large, he’s a regular guest on TV and radio, co-hosts the NPR podcast “Words Matter,” travels the world to lead workshops on dictionaries and the English language for the U.S. State Department, and judges a range of spelling bees, including the first to take place (in English) in Egypt, as the dictionary’s representative.

Considering that Merriam-Webster is the oldest dictionary in the country — first published in 1828 by founder Noah Webster, and the first to include words of American English — Sokolowski is thrilled that he’s still working for a company that almost 30 years ago made the vital decision to post its content on the web.

He credits the man who hired him, former Merriam-Webster President and Publisher John Morse.

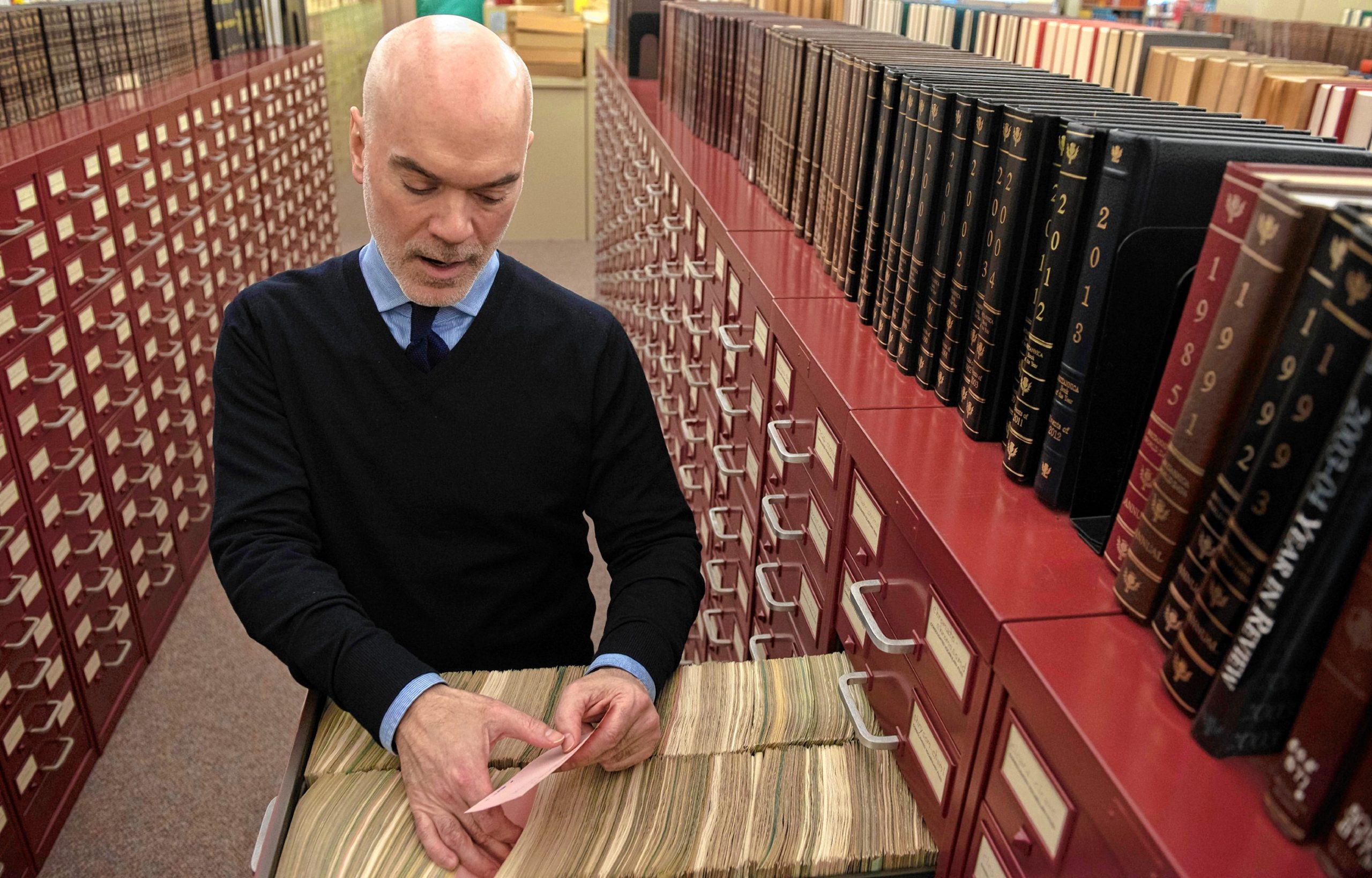

Peter Sokolowski, editor at large at Merriam-Webster, talks about his 30-year career at the venerable Springfield dictionary company and the many changes he’s seen. Several historic editions of the dictionary, as well as an old company sign, can be seen here. STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

“He put us online in 1996, and I feel he saved the business,” said Sokolowski. “He made it free and consistent with the company model, which was always to have good distribution at low prices.”

And Sokolowski, who lives in Easthampton, has embraced the dictionary’s ability in the Information Age to have a regular back and forth with the public on word usage, whether he’s posting on Twitter that it’s perfectly OK to end a sentence with a preposition, or writing blog posts as he examines what words people are investigating. The company’s website gets over 100 million page views a month.

“For the first 400 years of English language dictionaries, no publisher knew which words were being looked up,” he said with a laugh. “We are the first generation to see that, and I’ve been here to see the changes.”

Over the last several years, Merriam-Webster has also sometimes found itself at the crossroads of American political battles, notably after Donald Trump was elected president in 2016 and he and people in his administration bandied about terms like “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and “nothing burger” (all of which spiked people’s visits to the company’s website, Sokolowski notes).

“The stability of the dictionary is a source of comfort,” he said. “I think there’s a general sense that there is a neutral and objective arbiter of meaning and that is us, the dictionary. But with that comes a deep responsibility to be seen as neutral and not political.”

How do you say that in French?

Sokolowski, who grew up in eastern Massachusetts, studied French literature and language as an undergraduate at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, including a year he spent at the University of Paris, and he also earned a master’s degree in French literature at UMass.

After finishing his M.A. in 1994, he was considering a return to Paris to teach English when he responded to an ad seeking a French editor/translator for an unnamed publisher in Springfield.

“It turned to out be at Merriam-Webster, and I was going to be part of a team doing something no living editor there had done — writing a dictionary from scratch,” he said. “It seemed like a great opportunity.”

Merriam-Webster has a very active online presence today. But in years past, as Peter Sokolowski explains, decisions on adding new words to the dictionary generated vast paper records, called citation files, as seen here in the company’s Springfield headquarters. STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

In addition to helping develop the company’s first French-English dictionary, Sokolowski has worked on editions of Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary and another designed for advanced learners of English who are not native speakers.

But pretty early on, he says, his old boss John Morse also tapped him to travel with him to literary conventions and other forums where they’d staff an information booth and sell dictionaries.

“I learned so much from him informally during these trips,” he said. “I got this great private education that no one in the building had.”

It was odd, in one sense, for Sokolowski to take on this public presence for Merriam-Webster. He says most of his colleagues are “deeply shy people” and that he’s not much different: “If I were seated next to you in a restaurant, I would never talk to you first.”

But, he adds, he has no fear of public speaking and now enjoys being the company liaison in many capacities: for the media, for academics doing research, for teachers and other education professionals in countries such as Brazil, Mexico, Korea, Poland, and India where he has led workshops.

“American English is the best type of diplomacy,” he said, referring to these U.S. State Department-sponsored trips, which can put him on the road for two to three weeks at a time, though the schedule has eased since COVID-19.

And, he notes, “I get recognized in public airports a lot: ‘You’re the dictionary guy!’”

He’s also a voluble guy who during a tour of the Merriam-Webster offices reels off a wealth of information on the company’s history, pointing out vintage copies of old dictionaries and describing how the process for entering new words, or removing old ones whose use is outdated, has evolved over time.

It can take years for a new word to make its way into an updated version of the dictionary, and only after a rigorous review procedure that can involve multiple editors and executives. The building has a huge paper morgue where hundreds of thousands — perhaps millions — of old paper “citation files,” marked by hand and stamped by different editors, testify to how words once made their way into different Merriam-Webster editions.

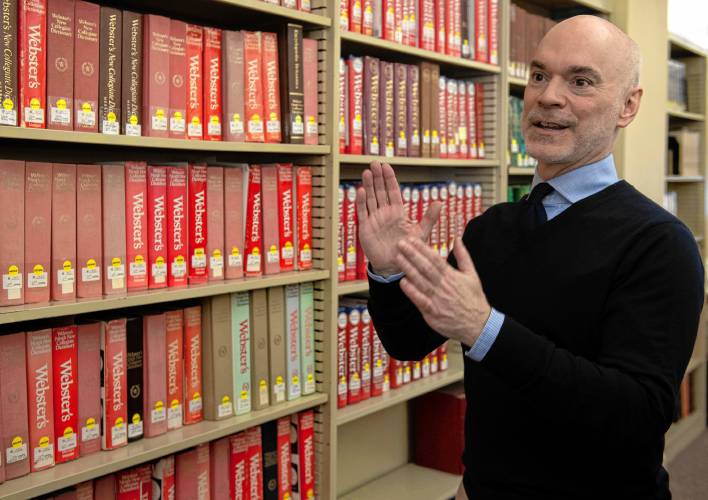

Peter Sokolowski, editor at large at Merriam-Webster, says he feels fortunate still to be doing a job he loves after 30 years at the Springfield dictionary company. A number of other American dictionary companies have folded during that time, something he calls “a joyless turns of events.” STAFF PHOTO/CAROL LOLLIS

These days, new words can make it into print when editors believe they’ve become a full part of public discourse, while words that Merriam-Webster sees as driven by public interest can end up on its website as a “Word of the Year,” which in turn can generate news stories.

“I find it ceaselessly interesting the way this all circles around,” he said.

Sokolowski has a busy work schedule, but he’s got plenty of other things going on in his life. He’s a freelance writer who’s currently writing a book on the history of the English language dictionary; a substitute jazz show host on New England Public Media; and a jazz trumpeter who has played in a number of swing bands over the years.

And if he’s saddened that a number of other American dictionary companies have folded in the last 20-odd years — “That’s a joyless turn of events and a sign of an unhealthy industry” — he feels very fortunate he’s been able to stay at a job he enjoys and can pursue his other interests.

“When I was 18 and starting at UMass, I was a French major, played in a band, and had a jazz show,” he said. “Now I’m 54 and my interests haven’t changed. I do the same thing … I have to pinch myself.”

Steve Pfarrer can be reached at spfarrer@gazettenet.com.