By Carolyn Brown

For the Valley Advocate

Michael Cohen’s friends knew him for two things: making a life in pottery and being the life of the party.

“He was very funny,” said Harriet Cohen, Michael’s ex-wife. “He could crack a joke … and he was much loved by everyone because he was a good boss. He was a wonderful father.”

Cohen, a celebrated potter and longtime Pelham resident, died on Jan. 9 at the age of 89. He founded the founder of the Asparagus Valley Potters Guild and his work is in the collections of American museums, including the Museum of Modern Art, and he authored several pottery books.

Outside of his professional accomplishments, he loved using his artistic talents for fun.

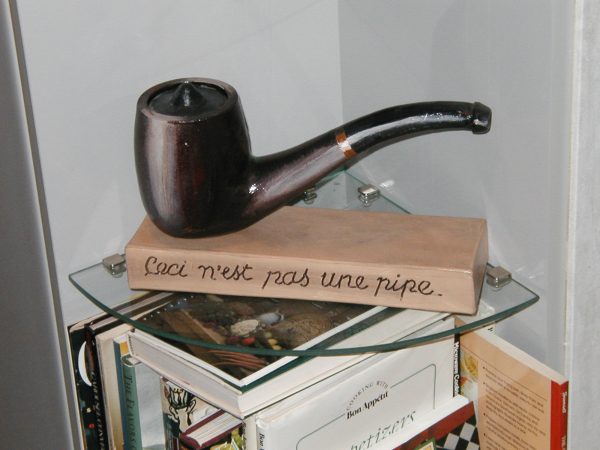

Amanda Cohen, his daughter, recalled that one year, for a friend’s Halloween party, he built a chess set where the pieces were shaped like body parts — rather than calling it “chess,” he called it “chest.” Another time, he made a teapot shaped like the pipe in René Magritte’s famous painting “The Treachery of Images” (better known by its caption, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.”) Another time, he made a ceramic chocolate bar with a bite taken out of it.

“I asked him, ‘How did you take the bite out of it?’ And he said, ‘I just took a bite out of it.’ He bit that clay!” Amanda said. “He could do anything with clay, and he let us do it, too.”

Cohen was born in Boston in 1936. As a child at day camp, he learned how to design and make marionettes and scenery for them. As a high school student, he was part of a program for gifted art students.

Cohen graduated from the Massachusetts College of Art in 1957, where he discovered ceramics in his sophomore year. After that, Cohen wrote in an autobiographical document in 2008, “There was no turning back.”

“He set an example for so many of us on how, simply, to be a potter,” said The Marks Project, an online database of ceramics artists, in a Facebook post.

Cohen then spent a summer working as a pottery assistant at the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Deer Isle, Maine. After that, he enlisted in the Army for three years and photographed potteries in several European countries. When he returned, he went to Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, for a year. In 1960, he set up a studio in his mother’s basement in Newton. In 1961, while back at Haystack, this time as a maintenance man. Cohen met his future wife, Harriet Cohen (nee Goodwin), whom he married in 1964. (The two later divorced, however.) They settled in New Hampshire before later moving to Pelham.

Gallerist Leslie Ferrin, who first met Cohen on a studio visit in the late 1970s when she was an undergraduate student at Hampshire College, said in an email, “He was a great storyteller and kept us laughing until it hurt with his biting, gallows humor as he delivered comic relief from the humbling reality of life as a self supporting artist.”

Michael and Harriet had two children, Amanda and Joshua.

“Dad was fun,” Amanda Cohen said. “Dad was a lot of fun.”

Amanda, who is now a stand-up comedian in California, called her dad “my biggest supporter” and said that he introduced her to comedy records, including those by George Carlin, Monty Python, and the Firesign Theatre. Cohen, a passionate film fan, also introduced his children to what he considered “culturally important” movies like “The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” “Blade Runner” and “Dark Star.”

Cohen loved to create novelty ceramics pieces, including a teapot shaped like the pipe in René Magritte’s famous painting “The Treachery of Images” (better known by its caption, “Ceci n’est pas une pipe.”) / COURTESY OF LESLIE FERRIN

“We would watch comedy movies, and he would explain certain joke structures to me, and he didn’t explain the joke. … I still use some of that stuff today in my writing, things that he was aware of,” she said.

His tastes were eclectic. He loved classical music, but he also brought home the first albums of the bands Devo and Gipsy Kings. He loved Akira Kurosawa movies as well as “trashy science fiction,” Amanda said — to him, they were equally valuable. He also loved movies by John Waters and even had a photo of drag queen Divine from the movie “Pink Flamingos” in their house.

He was such a fan of the arts, in fact, that he left money to the Bromery Center for the Arts (the Fine Arts Center) at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in his will.

Cohen also had a habit of creating learning experiences for his children at home, in his studio, and elsewhere. By participating in craft fairs with their father, the Cohen children learned the difference between wholesale and retail. Cohen also taught Amanda how to use power tools.

“One interesting thing about Michael is that he met challenges head-on,” Harriet Cohen said. “And if he needed a tool, if he was inventing a process and found that a certain kind of tool would be the right thing to do it, he would invent a tool! … He had a lot of different skills, and they all came into use in his work as a potter.”

Joshua eventually joined his father in the studio, and they created a line of blue tiles with stamped designs in the center. Cohen was also known for using sponge imprints in his work.

Cohen founded the Asparagus Valley Potters Guild, a group of professional potters, in 1976.

“Before that, he was even advising other potters, ‘You want to move to Massachusetts. You want to move to the Pioneer Valley. It’s a really good place for artists,’ and he knew that early on,” Amanda said.

He also helped found Studio Potter magazine, a publication written by and for professional potters.

Potter Bob Woo, who met Cohen in 1973, agreed that Cohen was “enthusiastically into everything” and “probably is the most eclectic aficionado I know. Michael was always the life of the party.”

Woo said he appreciated Cohen’s work because it was “very, very unique and individual” and had “simplicity and grace.” He appreciated Cohen’s policy and discipline. “He liked to say he didn’t leave the studio unless he did at least an hour’s worth of work on one of his one-of-a-kind pieces,” Woo said.

Overall, Woo wants people to remember Cohen as “a great craftsman and a wonderful friend.”

Amanda Cohen said that her father was always a good boss to his students and apprentices.

“He was really fair to them. He paid them well. He gave them paid vacations — all things he did not have to do because he was not a corporation,” she said. “He was not a company, but he was really, really caring to them. If there was a big snowstorm, ‘Well, it’s a paid day off. Things happen.’ And so he would keep employees for a long time.”

Garth Johnson, the Paul Phillips & Sharon Sullivan curator of ceramics at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York, where some of Cohen’s work is part of the permanent collection, said in an email, “Michael should definitely be remembered for his own spectacular achievements, but also how he set the stage for others. Everything Michael achieved helped others come together or build something new.”

Cohen’s pottery work also has its own staying power, which Amanda appreciates.

“One of the great things about pottery is that it is all but eternal. It will last for thousands of years. I’ve been to museums where I look at pottery from China 5,000 years ago, and it’s intact. … Pottery is taking a rock and molding it to the shape you want, and he was an expert at that, so there are little eternal pieces of his work all over the world,” she said.

“There’s pottery of his all over, and it will be around for a long time, and I love knowing that,” she added. “… It’s out there, and it always will be.”

Cohen’s family will hold a celebration of life in the spring, but the date and time have not yet been determined. Cohen’s work is currently on display in “The Mad MAD World of Jonathan Adler” at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York City through Sunday, April 19. For a more in-depth chronicle of Cohen’s life, check out his 2001 oral history interview with the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.