The committee that oversaw the 2011 legislative redistricting process recently released a report on its work—and it doesn’t mind saying that it did a pretty good job.

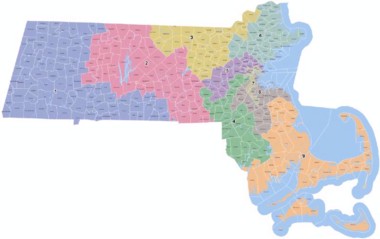

The December report was signed by the two Statehouse leaders who chaired the redistricting committee: Sen. Stan Rosenberg (D-Amherst) and Rep. Michael Moran (D-Brighton). Their committee was charged with redrawing Massachusetts’ legislative district lines to reflect new population figures from the 2010 federal census. The biggest, and least welcome, change was the loss of one of the commonwealth’s 10 congressional seats; in a development that came as a surprise to no one, Western Mass. took the hit, losing one of the two seats that had been based in the region.

Among its accomplishments, the redistricting committee noted its creation of new “majority-minority” districts around the state, where candidates of color are expected to have a better chance of election. There are now 20 House districts where people of color are in the majority, and three Senate districts, including the reconfigured Hampden Senate seat, which now includes more Springfield precincts. (This fall, incumbent Hampden Sen. James Welch, who is white, faced a Democratic primary challenge from Springfield city councilor Melvin Edwards, who is black, with Welch retaining the seat.)

In addition, the redrawn 7th Congressional district, which includes parts of Boston and Cambridge, is now 56 percent minority, making it “the strongest majority-minority congressional district in the state’s history,” the report noted.

The new districts, Rosenberg and Moran wrote, were established in keeping with the federal and state Constitutions and the U.S. Voting Rights Act and “were the natural outgrowth of the demographic changes within the Commonwealth; the Committee did not unduly subordinate traditional redistricting principles for racial considerations, but rather gave due weight to all of the competing legitimate state interests.”

*

The report also included recommendations for improving the redistricting process in future years, including changing the way prisoners are counted in the census.

Right now, the census records prisoners as residents of the places where they’re incarcerated, not the communities where they lived previously and where they’re likely to return after their release. Critics say this practice creates what the Easthampton-based Prison Policy Initiative calls “prison-based gerrymandering” and results in an imbalance of political power, inflating the populations of districts that are home to prisons. The practice “leads to a dramatic distortion of representation at local and state levels, and creates an inaccurate picture of community populations for research and planning purposes,” PPI notes. (See “The Prison Town Advantage,” Oct. 8, 2009, www.valleyadvocate.com.)

PPI has led the campaign to fix the problem, producing numerous reports showing the resulting political disparities in districts across the country. PPI also brought the matter to the attention of Massachusetts’ redistricting committee, whose report referred to the “tremendous amount of testimony and advice” it received on the issue. “We agree that the way prisoners are currently counted does a disservice to the state and should be changed,” the authors wrote.

The “most expedient and streamlined” fix, they went on, would be for Congress to call on the Census Bureau to change its policy on counting prisoners. “The tabulation of prisoners should be at the forefront of Bureau priorities in evaluating and adjusting how the 2020 U.S. Census will be conducted,” said the report, which also recommended that the Legislature pass a resolution expressing its support of such a change—and take more dramatic action if necessary. “If the federal government fails to act, then the only recourse is to amend the Massachusetts Constitution,” the report said. “Such a change on the federal level, however, will rectify the perceived inequalities in counting prisoners and eliminate costly litigation for states to defend redistricting plans based on adjusting prison populations.”

The redistricting committee’s strong recommendations were cheered by the Prison Policy Initiative, which notes the significant progress made on the issue this year. Several states (including New York, where the effects of prison-based gerrymandering have been especially pronounced) passed laws calling for prisoners to be counted at their previous homes for the purposes of state and local redistricting, and this summer, the U.S. Supreme upheld the law in Maryland.

*

One change Rosenberg and Moran do not support: taking redistricting responsibilities away from legislators and turning them over to an independent commission.

While Massachusetts’ Constitution calls for the Legislature to redraw district lines every 10 years based on Census data, there have been calls to create an independent body to, at minimum, make recommendations to legislators. Such a move, supporters say, would limit lawmakers’ ability to draw new district lines to serve political considerations.

As evidence of such abuses, they point to the messy redistricting process after the 2000 census, which was eventually scrapped by federal judges who found that new Massachusetts House districts had been drawn to protect incumbents. (The mess also resulted in then-House Speaker Tom Finneran’s conviction for obstruction of justice.)

In early 2011, Statehouse Republicans introduced a bill to create an independent redistricting commission, which would draw proposed maps that would then go to the Legislature for final approval. While the idea enjoyed both political and public support (Gov. Deval Patrick and Secretary of State Bill Galvin both backed it, as did two-thirds of respondents to a MassINC poll at the time), the bill was soundly defeated by the Democratic-controlled Legislature.

In their report, Rosenberg and Moran wrote that the most recent redistricting process “puts to rest the idea that the legislature should surrender its duty to create new districts to an independent commission.”

They continued: “The idea that a commission can produce districts that are fairer or eliminate the expensive litigation to defend a plan is not supported by the facts of the last two redistricting cycles.” Following the 2000 census, about two-thirds of redistricting plans in states that used independent commissions were legally challenged, compared to about half of plans created by state lawmakers, they wrote. And “to date, every state that used a redistricting commission as the primary method of creating districts for the 2012 elections had plans legally challenged,” they added.

“If court challenges are to be used as one benchmark to determine a successful redistricting effort, then commission-produced plans come up short,” wrote Rosenberg and Moran, who went on to praise the “open and inclusive process” their committee used. “The dialogue is what created the new districts in the Commonwealth. This inclusiveness strengthened the plans and we are thankful for the overwhelming public participation in a process that created fair and legally defensible districts. There is no reason to believe this would not be the case in the future.”•