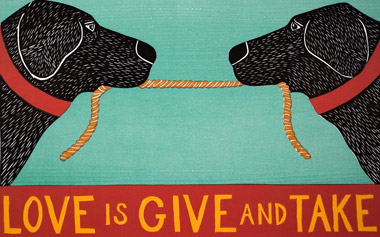

The late Vermont artist Stephen Huneck made works that are instantly recognizable—bright, accessible, folky depictions of dogs enjoying themselves. They’re sometimes readily categorizable as charming, often witty or funny. In one, a dog sniffs the nether regions of another. Below, it says “greetings.” In another, labelled “faux paw,” a dog walks through wet paint.

Huneck was apparently “discovered” in a manner to match: someone offered to buy one of his dog carvings, which Huneck, then dealing in antique furniture, hadn’t particularly been trying to sell. Huneck offhandedly said it would cost $1,000. The man, who indeed bought the work, turned out to be a New York art dealer.

Huneck became an internationally known artist. His St. Johnsbury studio was part of Dog Mountain, a 150-acre property that’s a freely accessible dog park of sorts, complete with trails, an agility course, and Huneck’s master work. That work is the Dog Chapel, a small version of the classic white Vermont church, which holds sculptures of dogs and even has dog-themed stained glass windows.

In a recent interview Huneck’s wife, Gwendolyn, told me why Huneck built the chapel: “Stephen built it because he thought there wasn’t a sufficient way for people to find closure when an animal died.”

The walls are covered with tributes to the deceased pets (mostly dogs, but, says Gwendolyn, also a range of pets from hamsters to horses) of visitors.

“His goal [in his art] was to heal, because he was trying to heal himself,” Gwendolyn says.

Part of what Stephen Huneck was trying to heal from was what happened when the severity of the economic downturn became clear. “We tried to keep everything going. We kept all our employees employed. At first we thought we could survive, and then what happened is for a while there people were scared and they stopped buying,” Gwendolyn says. “We weren’t getting low sales, we were getting no sales.

“Meanwhile, we still had quite a large staff. Eventually we just couldn’t do it anymore. We had to let almost everybody go.”

That hit Huneck hard. “He felt somehow it was his fault,” says Gwendolyn. “If you ask me, it was Wall Street’s fault.

“Stephen and I had a very close relationship. I knew he was suffering from depression. He was getting medical help, seeing a psychiatrist weekly. He mentioned to me, the day we had to fire everybody, that he was thinking about committing suicide, because he thought I would be better off financially,” says Gwendolyn. Her voice breaks with the difficulty of recalling it. “I told him, don’t do that, I couldn’t live without you.”

Shortly after, Huneck didn’t show up for his psychiatrist appointment. He had indeed committed suicide.

It’s an oft-cited perversity of the art world that death immediately increases the value of an artist’s work, and that suicide in particular creates more publicity. In the raw immediacy of the aftermath of Huneck’s death, Gwendolyn’s fears for their shared art-based business only increased. “I thought I was going to be a widow and homeless,” she says. “Things had gotten that bad.

“When news got out of his suicide, we were inundated with Web orders. What Stephen said, though it doesn’t make it worth it, was true.”

“We would have lost everything that we had worked so hard for. [The increased sales] enabled me to hire back most of the people that we had to lay off, because we had to fulfill all of these orders. I was determined to keep Dog Mountain open. We still struggle financially, but nothing like it was.”

Gwendolyn is a passionate advocate for her husband’s work. She explains that, accessible and folky though it may be, there’s a lot more going on. She says Stephen put great value in spirituality, and believed that art could be a force for healing. He wanted Dog Mountain to be a place that didn’t exclude anyone, that didn’t cater solely to the well-heeled art buyer. He wanted everyone, she explains, to be able to own some form of his art.

Knowing Huneck’s story adds something to the viewing of his art: what could seem cutesy or off-hand becomes something more poignant and vital.

“I am in discussion about maybe making part of Dog Mountain non-profit,” Gwendolyn says. “We don’t have any children, and I would like to see Dog Mountain survive when I’m gone.”

It’s easy to believe that it will.