Denis Kitchen has been a resident of the Pioneer Valley for 17 years, and his name is one that also carries decades’ worth of weight in the comic book industry. His publishing company Kitchen Sink Press (originally Krupp Comic Works) was one of the few successful independent “underground” publishers to survive beyond the 1980s, thanks to several successful titles including Mr. Natural, Bizarre Sex, Omaha the Cat Dancer and Dope Comix.

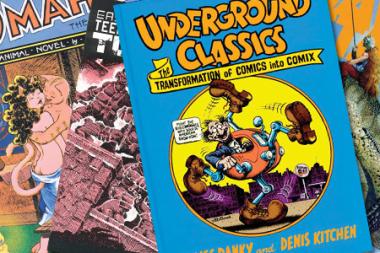

The imprint’s longevity was in part due to work by star talents/impresarios like R. Crumb, Richard Corben and Art Spiegelman, and a 1991 bump when the company was licensed to publish Grateful Dead Comix. It’s also known as the reprint home of Will Eisner’s work in The Spirit Magazine, classic comic strips by V.T. Hamlin (Alley Oop), Ernie Bushmiller (Nancy & Sluggo), Al Capp (Li’l Abner) and others, and for innovative, comic-themed merchandising of all kinds of products. Kitchen transplanted KSP to the Valley in 1993, when he saw a niche in the subculture that had begun to flourish here in the late 1980s. The recently published book Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix, by Kitchen and co-curator James Danky, is a gorgeous, full-color hardcover collection of plates from classic underground comics and priceless reflective writings by the creators and marketers of the original products and art historian Paul Buhle. The book’s arrival at the Advocate offices sparked memories of the Valley’s comic renaissance, and it seemed that week I could look around and still see traces of it everywhere.

The observant will pick out the stone gargoyles, still perched high above Northampton in quasi-Gothic stances evocative of Ghostbusters and The Hunchback of Notre Dame, lonely sentinels of the lost aesthetic that seasoned the four-story edifice at 140 Main Street, whose previous incarnation was the Words & Pictures Museum. An almost purely homegrown phenomenon bankrolled by Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles creator Kevin Eastman, the museum was (briefly) hailed as one of the foremost repositories of comic, cartoon and sequential art in American history. Northamptonites who’ve been around for a decade or more remember the downtown landmark’s once-marvelous facade and its haunted-house-like interior, featuring meticulously sculpted rooms, chambers and hallways, and including a voluminous bookstore and a 40-foot diorama of the Turtles scaling castle-textured walls or otherwise engaged in martial arts. Now the building houses AT&T—perhaps the ultimate sign that your artsy town has officially jumped the shark and landed squarely in a homogenized, mass-marketed version of its previous greatness.

Everything works that way, of course, especially art and music; a homegrown product is successful, then finds itself immediately pounced upon by the corporatocracy, co-opted, merchandised, reprinted, remastered, reissued and recycled 20 years later as easier to sell to the next generation than something they’d have to come up with entirely on their own. In some ways it’s vastly depressing, but at least, in a town like Northampton, we can still look back fondly on those few moments of relative spontaneity that called the piggies to the trough of what was genuinely, organically hip.

The history of comics and comic book culture in the Pioneer Valley is a rich one, and one that combines superhero and underground aesthetics, thanks largely to the Turtles, who broke in the mid-1980s. They were originally conceived as a one-off parody of the comics of that era, and the combination of sarcastic insider charm and genuine love of the genre made the title an instant darling of comic dealers and collectors everywhere, as did Eastman and co-creator Peter Laird’s savvy press blasts and catchy, quirky title. A limited-run print of the title’s first issue sold like hotcakes at a Portsmouth, N.H. comic convention, and subsequent print runs of ever-increasing size allowed them to drive the pilings for the foundation of their Mirage Studios empire into the ground of Florence’s industrial district.

Mirage (so named, according to legend, because Eastman and Laird in fact had no studio when they published the debut issue) cranked out a glut of material by creators like Eric Talbot, Simon Bisley, Ryan Brown, Mark Bode, Michael Dooney, Stephen Murphy (who went on to publish the ill-fated VMAG) and Jim Lawson, among others, and the TMNT franchise proliferated worldwide in the form of movies, TV shows, toys, games and hundreds of other franchise spin-offs. Eastman and Laird became multi-millionaires, and Mirage was bolstered by the success, launching several other titles and helping to revive such ailing cornerstones of the genre as Heavy Metal magazine.

For all the spectacle of Eastman’s post-Noho shenanigans (from frequenting Hollywood parties to marrying the fembot-esque model/actress Julie Strain) he did a lot to pay back Northampton and the underclass of marginalized comic writers and artists from which he sprang. In addition to funding the museum, he absorbed multi-milliondollar losses resulting from the idealistic business model he employed in founding Tundra Publishing, a company that, by Eastman’s account, was essentially muscled out of the market by the mainstream comic giants in retribution for siphoning off a chunk of their prime talent by offering highly competitive pay and superior creative control.

The later incarnations of Kitchen Sink Press and its eventual merger with Eastman’s ultimately cash-hemorrhaging Tundra (the deal that brought Kitchen to the Valley) shepherded that imprint through print runs of more evocative works of creative thought—graphic novels that explored complex emotions, situations and interpersonal relationships, including From Hell by Alan Moore (Watchmen) and Eddie Campbell (1991), The Crow by James O’Barr, and Cages, by British heavyweight Dave McKean (best known for his cover work on Neil Gaiman’s acclaimed Sandman series). Titles like these have helped push independent or underground comics toward aspirations to high art or literature (e.g. Spiegelman’s Pulitzer-winning Maus: A Survivor’s Tale), rather than in the direction that the superhero genre seems to have tacked—courting adaptations for blockbuster Hollywood films.

*

Even if you’re not so interested in comic books or comix culture, the Underground Classics is a fascinating study of how a cottage industry sprang up, thrived for a time in its own self-sustaining atmosphere, and ultimately was co-opted, marginalized or stamped out by corporate interests and moral crusaders of the ’70s and ’80s. Sometimes melancholy, but still peppered with tales of what must have been a seriously hedonist party, the story is recounted by participants. Their words sparkle with the sheen that only the experience of surviving such a wild ride can shellac onto a personality.

The book’s publication is linked to a traveling exhibit by the same name, and was partially funded by the show’s first stop, the Chazen Museum of Madison, Wis. Kitchen & Co. are in talks with other potential exhibit stops in Minneapolis, Oakland and Pittsburgh. The book showcases Kitchen’s academic side, and he admits to having historian tendencies.

“I have been involved in a lot of things like that,” he agreed in a recent Advocate interview. “There’s a group called Alexander Street Press that’s archiving in the neighborhood of 100,000 pages of comics in a searchable database, which is pretty historical, though back when we [Kitchen and other pioneering comix publishers in the late ’60s and early ’70s] started creating this stuff, we weren’t paying close attention to history. We were more concerned with paying the rent.”

Kitchen currently exists in the land of hodge-podge, approaching Dr. Seuss’ Bartholomew Cubbins in the number of hats he wears. He’s still in touch with many of the industry’s luminaries, and often is called on to help put projects together, like the recent Crumb undertaking, an entire illustrated comic version of the Bible’s Book of Genesis, which his literary agency, Kitchen & Hansen, placed with a publisher. He even has his hand in potential projects with Marvel and the venerable Stan Lee. He still publishes on a small scale through Denis Kitchen Publishing Co., LLC, and Dark Horse recently released The Oddly Compelling Art of Denis Kitchen, a collection of his own creative works.

In addition, Kitchen oversees the Denis Kitchen Art Agency, which represents the estates of Harvey Kurtzman (MAD Magzine, Playboy’s Little Annie Fannie), Will Eisner, Russell Keaton and Al Capp (among other clients), and which brokers the sale of original comic art, some of which can be quite pricey. He and his wife Stacey also operate Steve Krupp’s Gallery and Curio Shoppe at www.deniskitchen.com, where comics, artwork, merchandise and comic memorabilia can be perused and purchased. One hat that Kitchen has relinquished is the chairmanship of the Comic Book Legal Defense fund, which he founded in 1986 to provide assistance to comic creators who, he felt, were being denied First Amendment rights. That agency, which existed for a time in Northampton, has since moved to New York City.

Print media and publishing in general may seem to have a bleak future, but Kitchen has an optimistic view of the future of comics. He predicts that most of the buy-off-the-rack monthlies will probably go extinct, but that “graphic novels are here to stay, and I think you’ll increasingly see the proliferation of comics online. There was a sales report last year or so that said $650 million of ‘digital manga’ [a hugely popular and ubiquitous Japanese style of comics] was sold in Japan. And I think something like 10 to 15 percent of book sales in Europe are actually graphic novels. In those countries they appeal to everyone; both sexes, all age groups. In the U.S. it still seems to be mostly young males who buy them, though. Still, every major publishing house has a graphic novel department these days, and they just treat it like another genre.”

Though the Valley’s heyday as a center of comics culture has waned, the lure of the local life has kept some movers and shakers like Kitchen around, and with luck this place will be remembered as one where something did indeed bubble to a creative boil for a decade or so. In the meantime, Main Street shoppers should cast an occasional glance up at those gargoyles—there were nights in the ’90s when you could have sworn their eyes had lit up and followed you as you meandered home from the pub.