It is a comforting truism that the geekiest kids grow up to be the most interesting adults.

Indeed, it’s the stuff of countless movies and sitcoms and (familiar to those of us of a certain age) after-school specials: the geek, who initially suffers torment at the hands of his (let’s face it, it’s usually a boy) more socially suave peers, by the end of the tale emerges victorious over the bullies and lunchroom snubbers, through intellectual prowess or some heretofore unrecognized reserves of physical strength. His moment of glory is usually enjoyed in some public setting: the prom, the playing field, or, for audiences that can stand a little delayed gratification, the high-school reunion.

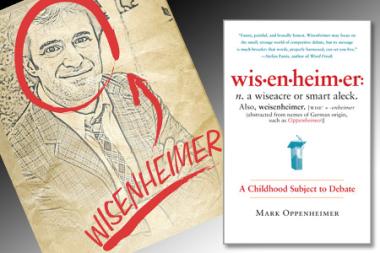

Mark Oppenheimer was that kid—or rather, a real-life version of that kid. His new memoir, Wisenheimer: A Childhood Subject to Debate (Free Press), contains all the key elements of the triumphant-geek teen movie: the bright but misfit square peg who spends his childhood negotiating a series of round holes; the deliverance, found through an unexpected venue; the eventual emergence as a thoughtful, fully formed adult, made fuller by the struggles of his early years.

In Oppenheimer’s case, his social stigma wasn’t caused by any of the burdens typically imposed by screenwriters: no paralyzing shyness or debilitating fashion sense or science-fiction fixation for him. His affliction was a less obvious one—at least, until he opened his mouth: a verbal precocity that, at first glance, might have seemed a blessing, but that in fact had the power to cause profound heartache for him and the people closest to him.

*

“From the time I learned my first words, my parents were worried,” writes Oppenheimer, who grew up in Springfield’s Forest Park neighborhood.

Baby’s first words are typically a source of delight; what parent doesn’t swoon the first time her kid’s babblings take shape as recognizable words? But Oppenheimer’s early language skills presented an unusual challenge. “For one thing, I never stopped talking,” he writes.

And his running patter went beyond the typical endless questions of the preschooler: “What my parents remember about me as a two-year-old accords perfectly with my own faint memories of that age: the unquenchable desire to say more, to be better understood, and, above all, to have conversations with adults.” Other kids, with their verbal slowness and limited attention spans, left Oppenheimer frustrated; he craved the focus and fluency of adult conversation.

That sounds charming—in small doses. “I knew very big words and knew how to use them,” Oppenheimer writes. “More than that, I had mastered the entire conversational affect of a much older person. …. When talking with me, people would forget my age.”

But while that degree of articulateness in a child amounts to a pretty neat “party trick,” he adds, it had its drawbacks. “[M]y gift, verbiage, presented a unique problem: you can have the words, but without the wisdom they don’t count for much.”

Even Oppenheimer’s family—a family of thinkers, talkers, language lovers—had their limits; some afternoons, his mother, home with toddler Mark and his infant brother, would call her husband at work and beg for respite. “Tim, you have to come home,” she would say. “He won’t stop talking.”

Things weren’t easier at school. “From the beginning, I had a hard time with teachers, and they had a hard time with me,” Oppenheimer writes. “In kindergarten, at Sumner Avenue School, I asked Mrs. Sessions what her first name was; she told me—it was Jean—but she wasn’t happy about it.”

After Sumner Avenue, Oppenheimer moved on to the Pioneer Valley Montessori School, where his love of books and language wasn’t exactly valued within the school’s “hands-on” pedagogical model.

“The school sold itself as a place where students could be individuals, but my endless quarreling, my hunger to challenge my teachers, wasn’t seen as a good urge that needed proper channeling; rather, it was treated as a rebellion against the harmony that the school was supposed to embody,” he writes.

That tension peaked during the two years Oppenheimer spent in the classroom of a stunningly unkind and immature teacher the students called—in the superficial intimacy of that Montessori classroom—by her first name, Lisa. “[F]or all of third and fourth grades I had the peculiar experience of being despised by my teacher, who drew on the deep well of loathing that most teachers have only for miscreants,” Oppenheimer writes. “At eight years old, I somehow had her number, even though I didn’t want it.”

The teacher’s open contempt for Oppenheimer was quickly adopted by his classmates—they were still at the age when identifying with authority figures was cooler than rebelling against them, he notes—making school a lonely and tense place for him. In one breathtaking example of cruelty, Lisa one day asked the entire class if any of them liked Oppenheimer, then gloated when no one spoke up.

He might not have wanted Lisa’s number, but once he had it, Oppenheimer couldn’t resist exploiting it. What once had been unintentional goading of his teacher became intentional; his language skills might have been the source of his problems, but they were also his strongest means of self-defense.

*

From there, Oppenheimer began to see the other ways his command of language presented him with a certain degree of power—power he did not always use to admirable ends. Sensing that the adults around him were ambivalent at best (and hostile at worst) about his purported verbal “gift,” he embraced its darker side. Frustrated by his social unease and feelings of rejection, Oppenheimer began seeking pleasure—short lived though it may have been—by frustrating others. In short, as he puts it, “I became a wiseass.”

His verbal acting out escalated, from teasing his younger brother to annoying but innocent-enough prank phone calls and to a series of practical jokes played on a girl he barely knew but who he feared was a competitor for his best friend’s attention. One day, the tricks went too far: Oppenheimer called a child abuse hotline, giving the girl’s name and claiming that she’d been sexually abused by her father. “The next week, the police arrived at her doorstep and nearly destroyed her family,” he writes. Six months later, the stunt was traced back to him; he avoided prosecution, he writes, thanks only to his attorney father’s ability to smooth things over at the police station.

Oppenheimer recalls, with the exactness of detail our most shameful memories carry, the afternoon when he nastily, pointlessly taunted the weary woman who worked the register at the Food Bag, a convenience store on Dickinson Street where he and his friends went to buy their after-school Twizzlers. While the 10-year-old Oppenheimer tried to justify his behavior at the time—the cashier was mean; she was especially rude to kids—he also recognized his cruelty.

“I was aware that she was poor, that her life was no picnic, that she probably tried her best,” he writes. “I was at Food Bag enough to know what hours she worked, and I knew that nobody in my family worked those kinds of hours. … Afterward, I felt worse about myself. Not only had I been cruel, I hadn’t even prevailed.”

As an adult, Oppenheimer sees his behavior with even more clarity. “A lot of what I did could be called youthful mischief, I suppose,” he writes. “But in truth I had become a bully. At the time, I would never have seen it that way. I didn’t beat anybody up. I didn’t stuff anyone in a locker. In school, I was the victim. But I was a bully in the only way I knew how.”

By this point in the story, Oppenheimer’s moment of salvation feels long overdue. It comes during his middle-school years—an age not typically known for its moments of grace and deliverance—at Wilbraham and Monson Academy.

Oppenheimer does not recall the school in the most flattering of terms. “The Academy was not a particularly good school,” he writes. “In general, you could say that some of the Academy’s students were there because they were too good for their old school, more because they were too bad, and the rest because somebody, the child or the parent, had ambitions they felt the public schools couldn’t support. We were not a student body with better futures.”

In truth, Oppenheimer ended up at Wilbraham and Monson because he was afraid of his neighborhood middle school in Forest Park. He wasn’t worried about drugs or gangs, but rather the pressure cooker created by all those early-adolescent hormones contained in one small space. Older friends already at Forest Park, he writes, “spoke of school dances where students necked under the bleachers; of notes passed in class conveying intelligence on who liked whom; and of study halls in the library during which students escaped behind bookshelves to continue what had begun under the bleachers at the dance. I was not ready for this scene.”

Wilbraham and Monson, he expected, would offer a smaller, more controlled atmosphere. What he was not expecting was that it would also be where he’d find the true love of his young life: the debate team.

“It’s pretty much true that if juvenile delinquents are boys with too much time on their hands, debaters are those with too many words,” he writes. “High school debate and oratory draw heavily from the ranks of the annoying: the walking dictionary, the wordsharp, the talker, the gasser, the jiver, the bloviator, the wisenheimer.”

Scouring the library card catalog researching debate topics, conferring with other kids who shared his quirks and passions and faculty coaches who understood them in ways so many other adults couldn’t, Oppenheimer found a joy and comfort that had been missing from his life. A boy like him, he writes, “turns to debate because it’s the one place where he can be rewarded for talking. His teacher may get exasperated by his compulsive hand-raising, his parents may tell him to stop arguing and just accept ‘Because I said so!’ and his friends may roll their eyes when he launches into yet another disquisition on drug legalization, the designated-hitter rule, or Apple versus IBM.

“But on the debate team, his facility with words and his fund of knowledge are unquestionably good. He may be useless at sports, but by debating he can win glory for his school. He may not have a wide circle of friends, but on the debate circuit he’ll meet peers from around the state, the country, even the world.”

Oppenheimer’s love affair with debate intensified when he entered high school at Loomis Chaffee, a private school just over the state line in Windsor, Conn. It was there that he fully embraced, and was embraced by, the world of New England prep school debate, a microcosm of the larger world, with its traditions and rhythms, its social hierarchies and expectations.

In Wisenheimer, Oppenheimer recreates the most exciting match-ups of his debating career—the nuances, the small moments that proved decisive turning points—with the sort of close play-by-play normally found in sports histories. And he describes, in loving detail, the teammates and rivals and coaches who populated that world. It was through debate that Oppenheimer experienced his first real romance (with a girl, rather than an argument), his first moments of stardom, and a social and intellectual satisfaction that had previously been so hard to find.

*

It is not giving away too much to reveal that Oppenheimer’s story has a happy ending. While his passion for debate ebbed by college, the gifts it brought him carried him into the kind of adulthood teen geeks so richly deserve. It’s included a graduate degree in religious history, a career in journalism (including a stint as editor of the Valley Advocate’s sister paper in New Haven), the publication of two earlier books, a wife and two daughters.

Oppenheimer acknowledges the irony in the fact that a boy who couldn’t stop talking ended up in a profession—journalism—that depends so much on the ability to listen. Or maybe it’s not such an unlikely leap after all.

“As a young child, speaking had been a pleasure but also a compulsion; there were times when I just couldn’t stop talking or arguing or explaining (even as my tearful mother pleaded with me to be quiet),” he writes. “[I]t was only once I found debate … that the urgency of talking, its needy quality, began to abate. Channeling my words into a sport was cathartic; it seemed to loosen some neurotic knot in my chest, and I became a far more relaxed, and generally quieter, person.”