shouts Sheila Siragusa, striding onto the stage from the empty auditorium. “Every molecule of you says, ‘I cannot wait to get out of this room and back to the theater.’”

She’s speaking to Susan Daniels, and her comment carries a certain irony. She’s directing a scene from a new play that takes place mostly in Northampton, and the theater that Daniels’ character can’t wait to get back to is the very theater this rehearsal is being held in—the very theater this play is about: the Academy of Music.

Nobody’s Girl, which receives its world premiere this weekend at the Academy, resurrects an all-but-forgotten episode in Valley history. It harks back to the early 1940s, and both the script, by UMass theater professor Harley Erdman, and Siragusa’s production evoke the period by zeroing in on the tone and flavor of the era’s movies.

The play revolves around Mildred Walker, a longtime employee at the Academy who was suddenly promoted to run the theater when manager Frank Shaughnessy was called to military service. The Academy, then primarily a movie theater, was held under lease by a film distribution company, whose directors attempted to oust Walker on the grounds that a woman should not be in a managerial position. The case became a cause-célébre and a front-page news story.

Mildred Walker herself was a lightning rod for controversy. A spirited, strong-willed woman from a working-class background, she was an unconventional character who carried on an affair with a married man and demanded a salary commensurate with Shaughnessy’s when she took over for him. Her story—discovered by chance in a box of old documents at the Academy—is a slice of history that sheds a revealing light on Northampton’s and the country’s past, a time when impending war was changing economic priorities and social roles.

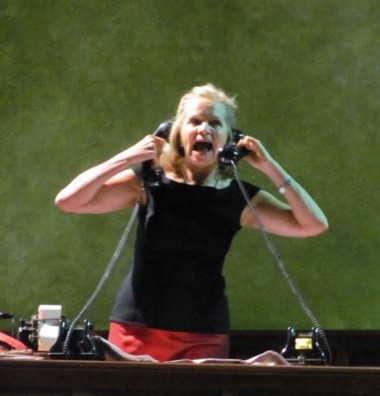

The sequence Siragusa is rehearsing on the Academy stage, where the multi-level set is still in skeleton form, is one of the few scenes in the play that doesn’t take place at the Academy. It’s a sometimes angry vignette between Mildred, played by Daniels, and her mother, played by Jeannine Haas. “Ma” is a grouchy old bird, unimpressed by the news Mildred brings home, that she’s been promoted to manager and is now earning the man-size salary of $43 a week.

“Let me tell you something, Millie,” Ma wheezes through a cloud of cigarette smoke. “In this world you’re either a wife, an old maid, or a whore. What you need is a good man, a strong man, to prop you up by day and pin you down by night.”

In addition to highlighting the theme of “a woman’s place” that Walker challenged (“I ain’t never been in favor of the New Woman,” Ma snarls. “It’s hard enough being an old one”), the scene also provides opportunity for nostalgic glimpses of old Northampton. Ma is reading the Daily Hampshire Gazette when Mildred enters, carrying a bag of provisions from Curran Brothers grocers on Main Street and sporting a new pair of silk hose from McCallum’s Department Store, in what is now the Thornes block.

During a break in rehearsal, Daniels munches a salad before going back onstage to rehearse a dance number—a high-flying fantasy sequence between Mildred and her risk-taking idol, Amelia Earhart. (Another personification of the liberated woman appeared in an early version of the script: Betty Friedan, who was a student at Smith College at the time the play takes place.)

“This role is so awesome for me because it’s so close to my life,” says Daniels, who managed a Valley summer theater, as its first female manager, after being an associate for many years, only to see it shut down, as happens briefly to the Academy during Nobody’s Girl. “But I didn’t have Millie’s mother,” she continues. “I was raised by a Millie, who told me my responsibility was to identify what my gifts are and to use them to give back. I honestly haven’t encountered too much sexism as a woman working in the theater, but like Millie, I’ve had to prove myself.”

Daniels says she also identifies with Walker’s drive and her aspiration “to make this theater a wonderful place, to make it even better. She’s fighting things beyond her control—the distributors are sending her second-rate movies, not as good as what’s playing at the Calvin. But, by her own bootstraps, she pulls herself up, and the theater with her. She has a relationship with a married man—the part that’s not like me!—but she’s okay with it because she’s getting everything she needs. She’s fulfilling her career desires, to take her skills and talents and use them in the world. She’s just a local girl, so this is really huge for her.”

The Mildred Walker in Daniels’ description finds more than a few echoes in the Academy’s current managing director, Debra J’Anthony. She’s the theater’s first female manager since Walker, and like the play’s heroine, she wants to “make it even better.” Under her leadership, the old movie house has once again become a venue for live stage shows—which was one of Walker’s ambitions too. As Mildred says in the play, her goal is to make the Academy “a theater of moxie and renown.”

The production is part of the Academy’s ongoing Women’s Work Initiative, aimed at increasing the involvement of women in all of the theater’s artistic and technical functions. J’Anthony points out that while 36 percent of all U.S. performing arts organizations are led by women (not exactly gender parity, but better than the less-than-20 percent of women playwrights and directors represented nationwide), 90 percent of the country’s major, high-budget theaters are headed by men.

“The historical episode the play is based on illuminates several issues that still resonate today,” J’Anthony says. “The ‘glass ceiling’ that impeded Mildred Walker’s rise to a managerial position stubbornly persists, and so does the practice, which Mildred fought against, of paying women less than men for the same work.”

Just as Walker strove to improve the Academy’s quality and appeal, J’Anthony has just overseen the completion of a major structural upgrade and interior renovation of the 115-year-old theater. Opening night of Nobody’s Girl marks the theater’s reopening, when patrons can admire the auditorium’s original ornamental plasterwork, restored and redecorated, while relaxing in brand-new seats.

Fiction Playing

with Fact

All the principal characters in the play are real-life people who were involved in the Walker controversy. While the plot roughly hews to the historical circumstances, the play is not a documentary but “fiction that plays with fact,” as Harley Erdman puts it in his author’s note on the play. “Nobody’s Girl is rooted in my belief that even forgotten people with ordinary lives are involved in ‘making history.’” Drawing on copious documentary research to flesh out his story, Erdman has incorporated the familiar character types and wisecracking style of the era’s movies, both the woman-centered “screwball” comedies of Preston Sturges and Howard Hawks, and Frank Capra’s crusading-little-guy dramas, with a climactic courtroom scene that smacks of both genres.

The cast is almost a Who’s Who of local professionals. In addition to Daniels and Haas, it includes Sam Rush as mild-mannered Frank Shaughnessy and Keith Langsdale in the dual role of a fast-talking, deal-making film distributor and a comically slick attorney. Steve Angel plays the bean-counting heavy, William Powell (“no relation to the movie star”); Macmillan Leslie, Jim Nutter and Mark Teffer are the Academy’s support staff—the movie-crazy boy usher, the tipsy handyman and the rakish projectionist—and young Molly Rush is a persistently perky Girl Scout.

The set, designed by Amy Putnam and Shawn Hill, contains six separate playing areas on a variety of levels, including a rolling central platform for the Academy’s front office, where many of the play’s key scenes, both combative and romantic, take place. Huge representations of broken movie reels and long strips of film hang symbolically above and behind the set. They are framed by blow-ups of period newspaper headlines, connecting news of the war in Europe and the Pacific to the local skirmish taking place downtown.

The period is captured in Siragusa’s staging as well. In addition to the fast-talking delivery of those ’40s movies, the actors’ gestures and attitudes evoke the films’ look and feel. There are even tableaus evoking iconic moments from films ranging from Bringing Up Baby to Casablanca. At one point in her scene with Ma, Mildred squares her shoulders and gazes out into the distance with a determined, Claudette Colbert-ish gleam in her eye and declaims, “I’m managing a movie theater, Ma, and I’m going to make it something better!”•

Nobody’s Girl plays Oct. 17-18, 8 p.m., at the Academy of Music, Northampton. Reservations (413) 584-9032 or academyofmusictheatre.com.

Chris Rohmann is at StageStruck@crocker.com. and his StageStruck blog is at valleyadvocate.com/blogs/stagestruck.