The Daily Hampshire Gazette, one of the oldest newspapers in America, printed its first pages in the summer of 1786. From the start, things were tense in the Western Mass communities it covered.

The front page of the earliest surviving issue of the Gazette reports that on August 29 a large crowd of people “assembled at the courthouse in Northampton, many of whom were armed with guns, swords, and other deadly weapons.” By taking over the building until midnight, “with drums beating and fifes playing,” the protesters were able to “prevent the sitting of the court, and the orderly administration of justice.”

This and other local acts of resistance led to a march on the Springfield Armory in early 1787, with Daniel Shays in the lead. Shays’ Rebellion was a political spark, caught off the cooling embers of the American Revolution, that quickly became one of the most profound crises in America. It was a true national emergency, leading to the Constitutional Convention and the creation of the Presidency just a few months later.

And as local author and history writer Dan Bullen points out, it’s a spark that never really faded. Bullen, who will be giving a presentation on Shays’ Rebellion on Saturday, March 9, at 2 p.m. at the Springfield Armory National Historic Site titled “Captain Daniel Shays and America’s First Nonviolent Protest,” says there are direct links to what Shays was protesting then to what people are protesting today.

“I’m interested in telling this as a story of things that are all still happening,” says Bullen, who grew up in the 1970s and ‘80s. “My generation was brought up on self-reliance, independence, personal success. But the health of the commonwealth is bigger than one person succeeding. People in high school now see protest as a form of breathing, a way of life. The younger the people I look at, the easier I think it is to feel optimistic about the future.”

As of this week, it looks like President Trump’s border wall national emergency declaration will face enough opposition from Republicans and Democrats to fail in both the House and Senate, requiring a presidential veto if Trump wants the national emergency to stand (which he likely will). This is a remarkable signal of distrust from the legislative branch. But just as remarkable have been the near-constant popular protests held across the country in recent years.

Some recent protests have vocalized a local response to broad national issues, like the gathering of 200 people outside Northampton City Hall this Presidents Day to protest Trump’s national emergency and border wall. “There are people who don’t have clean drinking water in our country who are being poisoned,” said State Representative Lindsay Sabadosa, referring to the city of Flint. “That’s an emergency.” State Rep. Mindy Domb went further, offering an A-B-C guide to current national emergencies. The list included gun violence, inadequate childcare, and climate change.

Eduardo Samaniego on the Valley Advocate Podcast

Other recent injustices have felt stingingly personal on the local level, as when activist and former Hampshire College student Eduardo Samaniego — who participated last year in a 250-mile DREAMers march for immigration reform — was detained by Immigration and Customs Enforcement, then deported to Mexico in February.

“What’s going on with Eduardo is an example of what’s going on with thousands of people, and not everyone has this incredible team of lawyers, activists and friends across the country,” Pioneer Valley Workers Center organizer Rose Bookbinder told the Gazette. “It’s scary what’s happening behind closed doors to immigrants across the country.”

Having seen, as Bookbinder put it, the “unjust system up close,” there is nothing to do but fight harder for justice.

In the 1700s, organizers had no help from social media or live video streaming, but their activism centered just as squarely and colorfully on social justice and economic inequality.

“America doesn’t like to talk about its class wars, especially when rich white people are making life miserable for others,” Bullen says. “But we hide it to our detriment. There is such a legacy of solidarity movements in this country. Women and men join up. Native Americans and immigrants get involved. These movements cross lines, because justice does that.”

But even when history doesn’t repeat itself, it tends to rhyme. Bullen’s presentation on March 9 was originally scheduled for January, the month of Shays’ confrontation at the Armory. Ironically, since the Armory museum and grounds are run by the National Park Service, the event was postponed due to the national government shutdown.

During those 35 days, the Armory’s doors were closed, and its federal workers were put on furlough. Talk of rising up against government dysfunction had to wait.

Casualties of class

If you can’t recall much about Shays’ Rebellion, you’re not alone. It might be for the same reasons you can’t recite the quadratic formula anymore, or haven’t picked up a copy of The Scarlet Letter since you were 15. Those skimmable, quizzable subjects we compressed into our schoolhouse years tend to stay there, moldering in the back of our memories, crammed into a mental filing cabinet marked “Not Useful in the Real World.”

That’s a shame, especially when it comes to history. Because the historical record is written by the winners, and people in power have a tendency to discredit those who resist them.

A Monument in Sheffield marking the location of the last battle of Shays’ Rebellion. Wikimedia commons

The leaders of Shays’ Rebellion were pushing back against high taxes, hardline debt collection, and property seizures imposed on poor borrowers, farmers, and rural tradespeople by the coastal merchant class. Calling themselves the Regulators, these hilltown organizers took direct nonviolent action after their petitions went unconsidered by the state legislature in Boston.

But those details do not appear in that Gazette article from 1786. Scan for the voices of the people, and you’ll be disappointed. This portrait of unrest was sketched not by a first-hand witness in Northampton, but by Governor James Bowdoin in Boston, who had a vested interest in painting the courthouse protesters as unruly rioters.

Bowdoin offers no explanation for why these farmers, neighbors, and families were coming out to meet in the streets. Instead he describes the protest, with fear-mongering flourish, as a “high-handed offence” fraught with “the most fatal and pernicious consequences” that would, just maybe, “dissolve our excellent Constitution, and introduce universal riots, anarchy, and confusion.”

Bowdoin’s proclamation called upon all judges, sheriffs, and law enforcement to prevent and suppress any further such public acts. This impulse to criminalize dissent was nothing new. Nor — as we’ve seen from Stonewall to Kent State, from Occupy to Ferguson — has it ever really gone away. It’s a dynamic observers of today’s politics know well — with a president who regularly uses speeches to demonize those who disagree with him, and a mainstream media generally willing to cover anything he says.

We are a young nation. Consider this: a 24-year-old American today has been alive for a full 10 percent of her country’s official story. Is it such a leap, then, to think of Shays’ Rebellion as recent history? Didn’t Bowdoin’s attempt to shore up Boston speculators’ bad credit ring a warning bell, of sorts, for America’s 2008 housing crisis, in which the big banks received government bailouts, but homeowners remained on the hook?

During this small handful of generations, economic injustice and class grievance have always gotten Americans down — then riled us into action.

“Much of what happened then is very similar to the kinds of things that are happening today,” says Bullen. He explains that his fascination with Shays’ Rebellion grew out of an interest in the Occupy movement about eight years ago.

“The fundamental issues are really similar,” he says. “We’re just experiencing them as new because we don’t keep these stories alive.”

Hopefully, learning about a resistance led largely by Scots-Irish farmers can also help us discuss deeper historical injustices carried out on this soil. The land that indebted American farmers stood to lose was first home to native tribes, themselves dispossessed. A century before Shays’ Rebellion, during King Philip’s War, New England settlers killed or enslaved roughly 8,000 Native Americans, and many more were forced to flee. Even after the Revolutionary War, the establishment of many farms and homesteads was premised on the aggressive displacement of Native Americans.

This is a singular shame that all Americans must carry. But many clashes since have also been shaped, in some way, by seizure and exploitation. “We see this dynamic today,” Bullen says. “Wealthy elites try to get more money out of poor people, and agitators try to rearrange the system and protect their property.”

In the years leading up to Shays’ Rebellion, the people of Massachusetts faced crushing taxes. These new policies favored rich merchants and speculators in Boston, who had fallen into debt with their international business partners following the Revolutionary War. Beyond Boston, many watched as their farms were seized and sold at auction. War veterans were hauled to debtor’s prison. Some stood to lose everything.

The state felt its authority was under threat. But this movement was decidedly nonviolent. That’s why Bullen would like to re-brand Shays’ Rebellion. He prefers to call it a resistance.

#Resist1786

“What we call Shays’ Rebellion started with a blatantly unfair land grab by the elites in Boston,” Bullen says. “People had fought the Revolutionary War for no pay, and now they were losing everything to wealthy speculators in Boston. The injustice was well known — it was in the papers. Other states adjusted their tax policy so that people wouldn’t take to the streets. Only in Massachusetts did the elites insist on such harsh terms that they drove the people to resistance.”

Photograph of Conkey’s Tavern in Pelham, near the home of Daniel Shays. The tavern became a meeting place for Shays in 1986-7. John Lovell Photograph Collection, Jones Library.

Shays marched on the Springfield Armory on January 25, 1787. At his side were more than 1,000 farmers and veterans from surrounding towns — an impressive number, given that the population of Springfield was just 1,500 at the time.

Shays and the protesters organized themselves into regional regiments, run by democratically elected committees. Although they were armed, their goal was to peacefully seize the Armory’s weapons before they could be retrieved by Bowdoin’s privately-funded militia of 3,000 men. The Governor’s troops, recruited mostly from Eastern Mass, were marching west to impose martial law in the Connecticut River Valley.

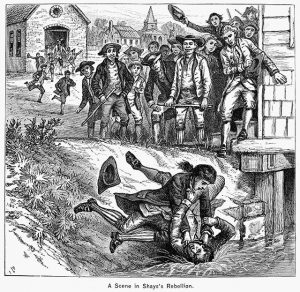

At the Armory, the Shaysites found the militia waiting for them. First the militia fired warning shots. Then they lowered the cannons and fired on the protesters. Four of Shays’ men were killed, and 20 more wounded. They fled north. Not a musket was fired from Shays’ side.

If Shays and the Regulators had taken over the arsenal, they might well have been better-armed than the Massachusetts militia, says park ranger Susan Ashman, who leads tours and public programs at the Armory. That kind of power can look pretty scary to those who live above the people. Perhaps this explains why those with the power to steer historical narratives so often lead us to reject rebel figures, or to forget them entirely.

Ashman, who is also the Armory’s historic weapons supervisor, says that the topic of Shays’ Rebellion always comes up among school groups visiting the Armory, but that adult visitors are far less likely to ask about it.

“It’s amazing that people don’t know about it, or forget about it,” says Ashman, adding that she grew up in California and didn’t learn about Shays’ act of resistance in school. But the Armory sees strong attendance at its weekend talks and special exhibits, including an exhibit on Daniel Shays and John Brown a couple of years ago.

As a result, Ashman says, the Armory is discussing a possible all-day seminar on Shays’ Rebellion, which would be held every year with multiple historians and speakers starting next January.

Most visitors who ask about Shays’ Rebellion just want a basic overview, Ashman says. “They want to know: was he such a bad guy? Personally, I don’t think so. They wanted the money owed to them after the Revolutionary War. They were facing heavy taxes. They were being jailed. We do a program about this with school groups, and they have to think: how would you feel if your father was put in jail for this reason?”

“Kids get up in arms about the injustice of it,” says Ashman. “It’s good to see that passion from them.”

“I always like stories about the common soldier,” she adds. “We lose the individuality of some of these historical events — we group them all together. But who are these farmers? What did they lose, and what happened when they tried to do something about it?”

Winning a Revolution

When Shays marched those protestors to the courts and then to the Armory, he was also fighting for public opinion. They had to show themselves to be nonviolent, dignified, and restrained.

“They could not look like a helter-skelter mob come out to ransack the country,” Bullen says. “The fear that too much democracy leads to anarchy was a myth propagated by the rich, just like today. But the Shaysites tried to show at every step that they were your neighbors. It was a fight for the heart of the people.”

“An Authentic Portrait of the Chief Insurgent” from 1878’s “Our First Century” by Richard Miller Devens.

Protests, then and now, tend to thrive when nonviolent, says Bullen. “The people can’t just have a righteous cause. We have to conduct ourselves so that everyone can see, from the poor to the relatively secure middle class, what we stand for. To earn trust, you have to be nonviolent. We’re seeing that now.”

Much has been said of the overlap in campaign rhetoric between Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump during the last presidential campaign (whether the latter actually believed in his populist talking points is another matter). But this theme spans the political spectrum: most Americans are not inherently against unequal wealth — they are against injustice and exploitation.

“Even at the time,” Bullen says, “they didn’t care that John Hancock and James Bowdoin were rich. They just didn’t want to be squeezed off their land by people abusing their power.”

It’s not such a huge leap to compare disenfranchised farmers in 1786 to young adults in 2019, many of whom are navigating a terrible job market with exploitative wages while carrying the burden of predatory student debt, and facing the vanishing chance of buying property or a home.

It’s about time to organize, and stay organized. Some already are. Many more might take note of how quickly, and closely, history tends to repeat itself.

“Captain Daniel Shays and America’s First Nonviolent Protest” will be presented in the Armory’s museum theater on Saturday, March 9, at 2 p.m. Admission is free, but reservations are required due to limited seating. For more information, call (413) 734-8551 or visit nps.gov/spar.

To get involved with local labor, equality, and social justice initiatives, explore opportunities with groups like the Pioneer Valley Workers’ Center, Western Mass Jobs with Justice, Indivisible.org, and the extension program at the Labor Center at UMass Amherst.

The Springfield Armory National Historic Site is open daily and runs a permanent exhibition on Shays’ Rebellion, including an interactive kiosk with audiovisual materials.

The companion website, run by STCC at shaysrebellion.stcc.edu, offers lots of local details, as does the book Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle by UMass Amherst historian Leonard Richards. Many local museums and historical societies can talk your ear off about Shays.

But don’t go looking for Shays’ historic home in Pelham — the site was flooded during the creation of the Quabbin Reservoir in the 1930s. That land, once shaped and cared for by small towns and farming families, now lies underneath billions of gallons of water that flow down, and east, to quench the city of Boston.

Contact Hunter Styles at hstyles@valleyadvocate.com.