Across Massachusetts people rely on natural gas to heat their homes and businesses, provide their electricity, cook meals every day, and for their hot water supply. Most of the time, natural gas, which is delivered to residents via local distribution lines, is relatively safe.

In this Sept. 13, 2018, file image taken from video provided by WCVB in Boston, flames consume the roof of a home following an explosion in Lawrence, Mass, a suburb of Boston. (WCVB via AP)

But in rare cases, such as the Merrimack Valley explosions, which occurred more than a year ago and resulted in about $1 billion in damages, 25 injuries, an evacuation of 30,000 residents across three towns, and the death of 18-year old Lawrence teen Leonel Rondon, natural gas can cause widespread devastation.

Western Massachusetts also has its fair share of gas leaks in communities across the area, which are worrying to local residents who fear that another gas explosion, like what took place a year ago in the Merrimack Valley, could possibly happen here.

Meanwhile, there’s a set of proposed Tennessee Gas and other utility company pipeline projects that would impact seven different communities in the Pioneer Valley — Longmeadow, West Springfield, Agawam, Springfield, Northampton, Easthampton, and Holyoke. Local environmental activists are opposing the project, but some elected officials see the projects as beneficial maintenance for existing natural gas pipelines.

The explosions in Merrimack Valley resulted in 80 fires with electricity going down, communications infrastructure failing, and smoke reducing visibility. In the months after the disaster, 44 miles of gas distribution pipelines and more than 5,000 service lines were replaced.

Aerial view of a burned out home impacted by the Sept. 13, 2018, natural gas explosion and fire in the Merrimack Valley in Massachusetts. Wikimedia commons image.

According to a Nov. 15, 2018, report by the National Transportation Safety Board, human errors made during a nearby gas pipe replacement resulted in the gas system quickly collapsing after a control system designed to repressurize the gas system failed.

In response to the disaster, Gov. Charlie Baker ordered the Department of Public Utilities (DPU) to commission a comprehensive independent assessment of the gas distribution system in the Commonwealth. In March, Gov. Baker signed legislation allocating $1.5 million toward the creation of that study by Texas-based Dynamic Risk Assessment Systems chosen by the DPU.

But Gov. Baker and the state of Massachusetts aren’t the only ones investigating the gas infrastructure in the Commonwealth. A coalition of more than 10 nonprofits called Gas Leaks Allies recently published its own 60-page study on Sept. 13 titled Rolling the Dice: Assessment of Gas System Safety in Massachusetts, which covers the condition of the gas systems, analyses gas incidents in the state, examines utility practices and DPU oversight, and looks at the future of natural gas in Massachusetts.

“Longer-term safety, health, and climate protection require an orderly, cost-effective, managed transition from dependence on gas to a safer, cleaner, and more resilient system based on renewable energy, thermal technologies, and energy efficiency,” it concludes.

The report also revealed that 15 percent of gas systems in Massachusetts were installed before 1940 compared to four percent nationally. The gas infrastructure also dates back to the 1800s and gas utilities must maintain 21,000 miles of pipes. Decades of neglect by gas utility companies also compound the problems in old pipes.

“This report reveals that the underlying assumptions of the gas delivery system are faulty,” the report reads. “It provides examples of how pipe materials fail on a regular basis, how the design of the system ensures … failures, and how gas can be unintentionally ignited. The report also describes the causes of leaks that trigger these incidents and outlines what can be learned from them, as well as what is lacking in official reports.”

The dangers of gas leaks

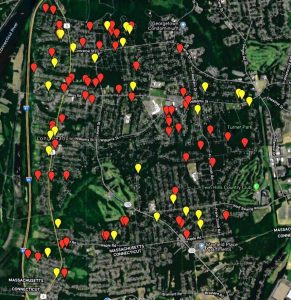

In the city of Springfield, 697 gas leaks were repaired, while 348 leaks went unrepaired in 2018, according to data from Cambridge-based nonprofit Home Energy Efficiency Team (HEET).

Gas leaks in Springfield. Red dots are repaired leaks while yellow dots represent unrepaired leaks. Source: HEET.

Springfield Fire Commissioner Bernard Calvi said gas leaks are graded from one to three. Grade 1 is a situation that requires emergency response and a risk of explosion, whereas Grades 2 and 3 constitute leaks that are non-explosive, with Grade 2 leaks releasing more gas than Grade 3 leaks.

Based on the data from HEET, the unrepaired leaks were all ranked Grade 2 or 3 leaks, whereas the repaired leaks were mostly Grade 1, but also included Grade 2 gas leaks.

Calvi said he’s found Columbia Gas to be responsive to 911 calls related to gas leaks or ruptures and described them as a “good corporate partner.”

Two incidents in the past year that took place in the city of Springfield related to gas leaks were both caused after home break-ins, according to Calvi. In both those incidents furnaces were stolen causing the gas lines to break, releasing free flowing gas into homes. Columbia Gas responded to both cases to mitigate the situation.

Audrey Schulman, executive director of HEET, who contributed to the Rolling the Dice report, said a new state law passed in 2018 now requires gas utility companies to fix larger leaks that release almost half of all emissions. Those leaks, which aren’t categorized as Grade 1, account for 7 percent of all the gas leaks in the state.

“They’re just spewing out gas,” she explained. “Last year, the gas companies had to transition to fixing those leaks also even if they are not potentially explosive. In this way, we can triage emissions. By fixing just a few leaks, we can cut emissions in half.”

Schulman argued that natural gas is an energy form of the 19th century and as a society we need to move forward with better and more renewable energy systems.

“Better technologies exist — ones that are not explosive, don’t create combustion gases in homes, which aren’t bad for the residents, ones that are just better for the environment and don’t have as much safety issues with them. I don’t believe that right now is the time to spend a lot of money putting in new infrastructure that costs an enormous amount per mile.”

At the same time, Schulman gives “huge credit” to gas utility companies for overall safe operation.

“We are piping an explosive gas into our buildings and lighting it on fire and piping that explosive gas underneath our streets all the time,” she added. “There’s very few explosions. It’s really remarkable. But at the same time that doesn’t change the inherent danger of it.”

Tanisha Arena, executive director of Arise for Social Justice, thinks gas leaks in the city of Springfield are a serious, ongoing issue for the city and other communities.

In March 2012, a natural gas explosion on Worthington Street leveled Scores Gentlemen’s Club, damaged 42 nearby buildings, and blew out windows in dozens of others. Next door to the strip club was Square One daycare, which was closed when the explosion took place around 5:20 p.m. A total of 18 people were injured as a result of the gas explosion, but there were no deaths that occurred.

The explosion was caused when a high-pressure gas line was accidentally punctured by a worker from Columbia Gas, according to then-State Fire Marshal Stephen Coan’s office.

“One of the properties was a daycare,” Arena explained. “If that had happened during business hours that would have had a completely different outcome. On the scale of Merrimack, that would have devastated Springfield.”

Arena said Arise for Social Justice reached out to Columbia Gas about fixing gas leaks, which resulted in 500 leaks being fixed.

“We don’t need more pipelines,” she explained. “We need the ones that are in existence taken care of, being repaired, maintained. And certainly the addition of the higher pressure on lines that are all leaky and faulty is just a recipe for disaster.”

According to Rolling the Dice, another gas incident took place in West Springfield in 2011. A gas rupture took place, which resulted in 200 people being evacuated from the Century Center Plaza. Another smaller gas leak took place in West Springfield this year on May 30, in which 11 homes were evacuated on Morgan Road. In both those incidents there were no injuries.

Agawam Mayor William Sapelli thinks that all energy infrastructure poses some inherent risks, whether for oil, electric, or gas. He said Columbia Gas, which serves Agawam, has been “more than accommodating” in terms of responding to gas leaks in his community.

Sapelli said whenever he’s needed to call Columbia Gas, they’ve responded immediately.

In 2018, 52 gas leaks were repaired, while 48 gas leaks went unrepaired in Agawam, according to data from HEET.

Sapelli said he believes it’s in Columbia Gas’s and other natural gas utility companies’ best interest to avoid catastrophic gas explosions such as the ones that took place a year ago in Merrimack Valley.

Gas leaks in Agawam. Red dots represent repaired leaks while yellow dots represent unrepaired. Source: HEET.

“Columbia Gas especially, and maybe because of that incident in Merrimack Valley, they’ve stepped up their effectiveness, efficiency, hiring practices, their preventive maintenance,” he added. “They’re on the spot right now. And they’re trying to repair some damage to their reputation, I’m sure. And they’re doing it in the right ways. They’re starting to be more accountable and oversight has tightened up quite a bit.”

The city of Holyoke often works hand in hand with Holyoke Gas & Electric to repair leaks in the city, Holyoke Mayor Alex Morse said.

“With the system that we have, it makes up a small percentage of lost capacity and I know that it’s a priority for them,” he added.

Currently there’s a moratorium on additional natural gas service in the city via Holyoke Gas & Electric, which began in February. Nearby communities such as Northampton and Easthampton have had moratoriums placed on new gas hookups since 2014.

In eight other towns in Franklin and Hampshire Counties, Berkshire Gas has maintained a moratorium since 2014. Those towns include Greenfield, Montague, Deerfield, Sunderland, Whatley, Amherst, Hadley, and Hatfield, according to the Greenfield Recorder.

“Right now we’re working on the assumption that there will be no more additional pipeline infrastructure built,” Morse said. “So, how do we work Gas & Electric to create demand-side management programs to get our biggest users using less gas to open up capacity to other customers?”

He also thinks it’s important that safety comes first when it comes to natural gas and replacing old and outdated gas infrastructure is part of the solution.

“I think it’s a concern everywhere,” Morse explained. “Yes, there are risks with any pipelines anywhere and so we have to be cognizant and aware of that. So, certainly with what happened in the Merrimack Valley, we don’t want that happening anywhere else in the state, and again, we should do everything that we can to keep people safe.”

Easthampton Mayor Nicole LaChapelle said on Aug. 12 there was a gas rupture near the Admiral Street area after a utility worker accidentally damaged a gas line. Columbia Gas quickly resolved the issue, homes were evacuated, but residents were back at home by the end of the day.

In 2018, there were 25 gas leaks that were repaired compared with 17 that went unrepaired in Easthampton, according to data from HEET.

For LaChapelle it remains a priority to investigate gas leaks in her community, specifically those located near residential homes, businesses, or public buildings such as schools.

She said she’s met with Columbia Gas President Mark Kempic regarding learning more about the existing gas leaks in her community, but has also gained another perspective from local activists with Climate Action Now Western Mass.

“We have seen some gas leaks repaired since I’ve taken office,” LaChapelle noted. “I put it on Columbia Gas that some [leaks] are not all. And because something is rated as a low risk or a small leak, I have no confidence that it will stay at that grade.”

Gas leaks in Easthampton. The red dots represent repaired leaks while yellow dots represent unrepaired leaks. Source: HEET.

LaChapelle said with the current gas moratorium in place in Easthampton, fixing gas leaks are first on her list as opposed to expanding capacity.

“The desire for gas in Easthampton centers a lot around businesses and those who need or want gas, especially in restaurants,” she added. “There’s certainly interest. When we’re talking to developers or really small business owners, gas is a part of the equation.”

Robert Ackley, founder of Southboro-based Gas Safety, Inc., and a co-writer of Rolling the Dice, worked previously for gas companies in the Northeast before starting his own company. Now he spends his time mapping gas leaks or infrastructure, training new gas inspectors, as well as inspecting buildings and gas system lines for leaks, though he said he has experienced pushback.

“The gas industry doesn’t like an insider coming out and telling what’s really going on,” he explained.

With the publication of Rolling the Dice, Ackley hopes within the next three to five years Massachusetts will move away from loosely categorizing gas leaks and improve standards and transparency about the dangers of leaks, the timeline for gas repairs as well as the damage to trees and other plant life.

“People have no idea that gas can kill your trees or your shrubs or kill your lawn,” he added. “I was at a person’s house two days ago and they had a gas leak in their catch basin. Well, the gas was leaking right in there and coming right out at the end of their driveway creating a huge odor in there on their property and their neighborhood. These types of things go on and on all the time.”

He said gas companies don’t fix these smaller leaks because they’re not classified as explosion hazards, but argued that anytime someone smells a gas leak, that should require gas utility companies to fix a leak.

“You come out your front door and you smell gas, I mean you don’t know if there’s a new leak that’s occurred,” he explained. “You can’t expect that just because there’s one leak there, another leak never occurs. When is there another leak that’s going to blow your house up?”

Fighting against pipeline upgrades

Tennessee Gas (a subsidiary of Kinder Morgan) and other gas utility companies have proposed a series of pipeline projects for western Massachusetts, one of which is “261 Upgrade Projects,” named for Compressor Station 261 located in Agawam. The goal, according to Kinder Morgan’s website, is to add 72,400 dekatherms (about 72.4 million cubic feet) per day of additional gas capacity on the existing Tennessee Gas pipeline system, which runs south from Northampton down through Easthampton, Holyoke, Westfield, and Southwick, and then moves east through Agawam, Longmeadow, East Longmeadow, and Hampden, before reaching Monson. The line also continues south into Connecticut.

A media representative for Kinder Morgan declined to comment about the projects, referring the Valley Advocate to its website for data instead.

But Kathryn Eiseman, president of the Pipeline Awareness Network for the Northeast, a nonprofit organization that collects data on pipelines across the Northeast, believes the overall gas expansion project is designed to create excess capacity that “no one has contracted for.”

She added, “That could go to power generators. It could go east along the major pipeline or marketers who sell it to whomever along the way.”

Eiseman said Tennessee Gas has proposed a six-mile pipeline through West Springfield to connect with the Holyoke system. And then there would be a “capacity swap,” which would free up gas along the Northampton lateral of the pipeline.

In an open letter to local area residents, Columbia Gas stated it would replace 8,500 feet of existing line with new pipe in West Springfield.

“That gives a lot of additional gas to Easthampton and Northampton,” she explained. “And this proposal also included increasing gas to Holyoke by almost 50 percent. It was a major expansion for Holyoke, too.”

Holyoke Mayor Morse announced his opposition to the pipeline project publicly this year on Earth Day. He argued that it’s time for elected officials take a stance and move the conversation on energy away from fossil fuels.

“Rather than spending $30 million to expand the gas pipeline that would only really last a handful of years and we’d be in the same position again in a few years from now, it’s important that we go big and spend that money on renewable energy sources,” Morse told the Valley Advocate.

Columbia Gas has signed a contract with Holyoke Gas & Electric (HG&E) to expand natural gas use, but it can be terminated without liability to HG&E if Columbia Gas doesn’t build the pipeline, Eiseman said.

“Columbia Gas has not even applied to build that pipeline, so if it hasn’t been approved by the DPU by the end of this year, December, HG&E has two weeks in which it can cancel that contract,” she added. “There’s no way [Columbia Gas] can get approval in that time. It takes about a year to go through the [state’s regulatory] citing board process.”

Westfield and Holyoke have their own municipal utility companies, while the rest of the Valley is served by either Berkshire Gas in Northampton up through Greenfield or Columbia Gas in Hampden County, Eiseman said, adding that gas utility companies have been in favor of the project because it would expand capacity.

She argued that the existing moratoriums on gas in communities such as Northampton, Easthampton, Holyoke, Greenfield, and elsewhere in the Valley, are unnecessary.

“One reason why there is ‘not enough gas on the pipeline’ is the inefficiencies,” she explained. “If there was a massive weatherization effort, everyone would be using less gas. And there would be gas for those pizza ovens or whoever is saying they need more gas.”

The Agawam portion of the project would involve an installation of 2.1 miles of 12-inch pipeline that runs in a loop parallel and adjacent to the existing Tennessee Gas pipeline.

The company would also remove an inactive six-inch pipeline and replace it with a new 12-inch pipeline. The project in Agawam would also involve replacing two existing turbine compressor units “with one new, cleaner burning turbine compressor unit as well as the installation of auxiliary facilities at [the] existing Compressor Station 261.”

Eiseman, a former lawyer and resident of Cummington, said that compressor upgrade could help Tennessee Gas to move gas east to serve other parts of the state in addition to bringing more natural gas to the Valley.

“This project is not so much about gas being exported as much as they are trying to saturate the local markets with gas,” she explained.

But Agawam Mayor Sapelli thinks the project would be beneficial to his community. Tennessee Gas has had a presence in Agawam since the 1960s and has a proven track record working with the city.

“What people have to realize here in Agawam is what they’re proposing is to replace two old compressors,” he added. “Anytime you do upgrades on equipment, no matter what the business is, that’s a positive thing. You gain more efficient and effective equipment. These two old compressors that they’re replacing are in the neighborhood of 50 years old each.”

Another upgrade for the project would be the installation of two miles of looped pipeline.

“They’re replacing an old pipe. How is that not a good thing?” he asked. “And with the technology that we have today, the pipes are more effective and efficient, not to mention that they’re going to put a device in their that’s going to automatically inspect and clean the pipe called a pig launcher.”

But what’s the timeline for the 261 Projects in Agawam? According to information on Kinder Morgan’s website “pending receipt of all permits, construction will begin in March 2020 for the Looping Project and May 2020 for the HP Replacement Project. The projects are expected to be in service in November 2020.”

The pipeline project also includes an expansion of a new large pipeline through Springfield to Longmeadow, where a new metering station would be built.

Longmeadow says ‘No’

In August, more than 250 residents during a Special Town Meeting voted to establish a bylaw disallowing the metering station at the proposed Longmeadow Country Club location, which was in a residential zone area nearby to Wolf Swamp Road Elementary School. However, a metering station could be built in an agricultural zoned area in the town.

The Valley Advocate previously reported that Longmeadow Select Board member Mark Gold opposed the project, calling Columbia Gas “unworthy” due to the explosions that took place in Merrimack Valley.

“I think the metering station has no place in the town of Longmeadow, especially that spot in the town of Longmeadow, and I hope whatever we can do to discourage Tennessee Gas from putting it there is what we ought to do,” Gold told the Valley Advocate back in August.

Michele Marantz speaks to a special Town Meeting in Longmeadow on Aug. 20, 2019. Chris Goudreau photo

Longmeadow Pipeline Awareness Group founder and town resident Michele Marantz, who submitted the Special Town Meeting bylaw change, said the next step is for her group to lobby local, state, and federal elected officials to oppose the project, including Congressman Richard Neal.

For Marantz, the pipeline project is in her view not only damaging to the environment and local communities, but a “threat to democracy.”

“Right now, gas companies can act with near impunity in local communities,” she added. “They appear to have no obligation to inform officials or residents about what they plan to do. There appears to be no mandate or requirement that they repair leaks when they’re identified.”

Marantz said she thinks agencies such as FERC and the DPU aren’t looking out for the best interest or protections of citizens.

“They appear to act mostly at the bidding of the gas companies, not in response to citizen concerns,” she noted. “And that doesn’t appear to be right to me.”

Gas leaks in Longmeadow. Red dots represent repaired leaks while yellow dots represent unrepaired leaks. Source: HEET.

In a March 25 letter to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), State Sen. Eric Lesser (D-Longmeadow) stated his opposition to the pipeline in Longmeadow.

“Over the past several months, however, I have responded to countless constituents who have contacted my office in opposition to the proposed Longmeadow Station,” Lesser wrote. “Many citizens and organizations in the Longmeadow community, including the Longmeadow Pipeline Awareness Group, have raised concerns about the potential for significant negative impacts to the health and safety of the Longmeadow community were the Meter Station to be constructed.

He cited issues regarding air quality with the release of pollutants as well as greenhouse gases that would contribute to climate change, adding that children and elderly residents would be affected most of all.

“Metering stations relieve pressure by blowing off raw methane as the station reduces gas pressure in the transfer of gas from one pipeline source to another,” Lesser wrote. “As a result, metering stations continually emit methane and other harmful contaminants that contribute to human health risks such as cardiovascular and respiratory disease, fetal/neonatal illness, and brain lesions that cause neurobehavioral abnormalities.”

In a more than 1,800-page filing by Kinder Morgan to FERC from Oct. 19, 2018, there’s also a proposed Berkshire Gas construction of 19 miles of 12-inch pipeline starting on the existing Tennessee Gas line and extending to the Northampton meter station.

“Project would include a new regulator station in Greenfield and would require Tennessee to replace its Northampton Meter Station. Proposed routes still in development, but would pass through Hampden and Hampshire Counties, through city/ towns. New/ replacement aboveground facilities in Greenfield and Northampton. Project design is ‘still in its infancy,’” a part of the proposal reads.

In Easthampton, Mayor LaChapelle is unsure how the gas pipeline projects would impact her community, and said she is getting little information from the Department of Public Utilities.

“Do I have concerns with natural gas and what happened in the Merrimack Valley and what it says about the rest of the state and Columbia Gas? Sure. I am pushing for answers from Columbia Gas. But when it comes down to it, I’m looking at the regulatory agencies and I’m not seeing a lot of direction today,” she said.

Eiseman said the overall project was discovered in 2017 when Tennessee Gas submitted its Long Range and Forecast Supply plan to the DPU. Every two years, investor-owned utility companies are required by law to submit a long range plan. And by the end of this month, Tennessee Gas is required to file a new forecast.

As it stands, there will likely be a large amount of wasted pipeline in the ground even as the state inches towards relying on more and more renewable energy sources every year via the state’s plan to reduce 80 percent of emissions by 2050, Schulman said.

“In order to do that, we’re going to have to get off gas,” she explained. “The question is how do we do that and how do we start planning and moving towards that? And meanwhile, the gas companies are putting in an enormous amount of infrastructure replacing the old leaky pipes at a huge loss to the gas customers.”

Part of the solution for Schulman is for the state and federal government to allow gas companies who want to explore renewable energy sources to switch from fossil fuels to power sources that don’t release greenhouse gases into the atmosphere

“That will allow for a graceful transition to the future that we all need,” she added.

Getting off gas for good

But community leaders in Western Massachusetts and elsewhere across the state are thinking about the future of our energy systems in the commonwealth. Here in the Valley, local communities have been working to wean themselves off of fossil fuels through renewable energy sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal.

At the same time, natural gas made up nearly one third of all energy consumed in Massachusetts in 2017, the most recent year profiled by the U.S. Energy Information Administration. It was by far the state’s largest source of energy.

HEET executive director Audrey Schulman said the group is working to develop a pilot for a geothermal project and one of the sites being explored is Holyoke.

“We are working with the gas companies currently to try to pilot a street segment geothermal project where water would deliver the heating and cooling that we need,” she explained. “And the geothermal would mean that the energy is coming from the Earth.”

She added the project would entail using energy at a maximum of 500 feet underground in the gas company’s right-of-way on municipal streets.

“You’d have the bore holes in the street and then they would be connected to a shared loop of water,” Schulman explained. “Instead of the gas pipe running down the street, there would be a water pipe doing a loop through the bore holes and then back to the beginning of the street. And then there’d be service lines into each building. And in each building there would be a heat pump that would take the heating or cooling that it wanted off of that water and deliver it into the home.”

HEET completed a statewide feasibility study that found that if the pilot project were implemented in cities across the state it could deliver 100 percent of the heating and cooling needs for a significant portion of Massachusetts.

“It’s going to depend a lot on the density of the infrastructure,” she added. “In downtown Boston, that’s too dense to deliver 100 percent of the heating and cooling. And in some places where the homes are very distant, it’s probably not worth installing it.”

But for cities like Holyoke, this project could be feasible, she said.

“We’ve talked a little bit with the town of Holyoke because we know they don’t want the new gas being delivered there,” Schulman explained. “And for a variety of reasons they’re a good site.”

Morse said he thinks geothermal energy could work alongside Holyoke’s existing renewable energy sources.

“I think it’s one option for us,” he explained. “What’s really special about Holyoke is after my announcement [opposing natural gas pipelines in the city], there’s been a lot of organizers, activists, climate scientists, and experts that have offered their help. We think that Holyoke can be a model for other cities and regions around the country about how you support economic development and transition a city off natural gas without needing additional gas pipeline infrastructure.”

Right now, the city relies on solar and hydro power. It’s already transitioned away from coal by transforming the old defunct Mount Tom coal-fired power plant into a solar farm with 17,000 panels with a three-megawatt battery storage system, the largest in the state, he added.

“We want to show that it is possible to go 100 percent renewable,” Morse said. “We’re going to be planning to get more specific on these goals with a timeline and metrics and goal posts along the way as to how we’re going to get there.”

In neighboring Easthampton, Mayor LaChapelle thinks there’s a four-pronged approach to weaning the Valley and the rest of the state off of natural gas.

“I like solar, wind, hydro, and geothermal systems,” she said. “Certainly in Easthampton, what we’re seeing in the big switchover is solar. In the past, we’ve looked at wind, but it was just too small of a project.”

LaChapelle said right now the city is working with a local developer to potentially revitalize a small hydroelectric plant that remains on a property in town.

As Eiseman sees it, the gas companies should be moving away from fossil fuels because she also thinks in the long-term, the state will be moving away from greenhouse polluting forms of energy.

Sapelli thinks the state should continue to move away from fossil fuels, but that’s impractical in reality to switch to immediately switch to all or mostly renewable energy sources. He’d like to see Massachusetts incrementally wean itself off natural gas and other fossil fuels. In Agawam, the community is working to reduce fuel consumption through energy efficiency, he said.

“For people to say, ‘We’re going to stop using oil and gas.’ Well, yeah, eventually. But right now. Tomorrow can we do that? No, we can’t do that … You really have to think it out and be practical, but you also have to be conscious of the climate and the damage that’s being done. That’s not fake. That’s real.”

Chris Goudreau can be reached at cgoudreau@valleyadvocate.com.